Donna de Varona Celebrated Her First World Record 60 Years Ago This Day A Trailblazer Just Into Her Teens

Today marks the 60th anniversary of the first World record set by Donna de Varona over 400m medley. At 13 years, 2 months and 19 days old, on July 15, 1960, in Indianapolis, the American pioneer clocked 5:36.5 over 400m medley. By the time she retired, she had left the standard at 5:14.9, via six global standards in a career crowned by Olympic gold.

At Tokyo 1964, ‘Donna Dee’ – as de Varona was known back then – achieved sporting immortality by becoming the first Olympic 400m medley champion as the four-stroke event joined the Games program eight years after butterfly’s Olympic debut at Melbourne 1956. She would go on to be a prize-winning commentator on Olympic sport and a passionate advocate for women’s rights, athletes’ rights and athlete representation.

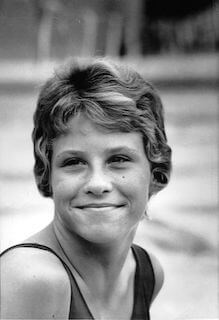

Donna de Varona – Photo Courtesy: Donna de Varona

Had Olympic and swimming bosses been a touch swifter with their decision-making, de Varona would likely have been 400m medley champion at Rome 1960, too: at 13, she would have been the youngest Gold medallist in Olympic history (a record held by U.S. diver Marjorie Gestring, who was 13 years and 263 days old at Berlin 1936).

The baby of Team USA at the 1960 Games in the eternal city two months after she set her first World record, de Varona swam for the U.S. team in the heats of the 4×100 freestyle relay but in 1960 there were no medals for those who raced their nation into the final.

Rome might have reaped two gold medals but de Varona had to wait four years until Tokyo 1964 to claim that count: her first gold came in the 4x100m freestyle final alongside Sharon Stouder, Pokey Watson and Kathy Ellis in a World record of 4:03.8, 3.1sec ahead of an Australian quartet that included Dawn Fraser at what would be her last Games and the Olympics at which she founded the Triple Crown Club (100m freestyle, 1956, 1960, 1964).

Two days after the relay, De Varona made it gold number 2 with one of her own: in an Olympic record of 5:18.7. De Varona had been battling a fever heading into the 400m medley final. She was expected to win, however, on the strength of her world record weeks before. “All I remember is relief when I won the gold,’’ she said recently.

Shy of the 5:14.9 World record she had established a few weeks before at Trials, she was still more than five seconds clear of USA team-mate Sharon Finneran, the American sweep completed by Martha Randall, just 0.1sec apart on 5:24.1 and 5:24.2.

In the stands to cheer her on and celebrate her triumph were de Varona’s parents, David and Martha. Her father had been a member of the University of California rowing team and may have made the 1940 Olympic Games had they not been cancelled due to the Second World War in which he served as paratrooper.

Last month, journalist Stephen Wilson caught up with Donna de Varona for his Wilson’s World column at Aroundtherings.com. She recalled the troubled history between Japan and the United States (and the Allies) and with a nod to her father and the healing power of time and effort, said:

“Twenty-four years later there he was in former enemy territory as the house guest of a welcoming Japanese family.”

Donna de Varona – where advocacy and representation began

Donna de Varona – Photo Courtesy: Swimming World Archive

Wilson tells a lovely story about Rome 1960 and the kindness of German Olympic-medallist rower Juergen Schroeder, who would go on to help Munich secure the 1972 Olympics.

Later, Schroeder worked with de Varona at the landmark 1981 Olympic Congress in Baden-Baden as athletes – including Thomas Bach and Sebastian Coe – played a leading role in the debate that paved the way for the creation of the IOC Athletes’ Commission. Almost 40 years on, athletes are now pressing for athlete representation to move two the next level – independence: they feel let down by an in-house athlete representative system that all too often and on too many issues represents the views of governors not athletes.

When de Varona looked back on her decades of broadcast and advocacy work, she told Wilson: “I never thought my entire life’s journey would be anchored by sport.”

Now 73, she recalls Tokyo 1964 as a platform from which she would spring into the rest of life at a time when there was no college scholarship available for women. She told Wilson:

“Those Olympics sent me on an incredible journey. Where would I be without the Games and the podium and the relationships I made?”

In Tokyo, de Varona met Bill Bradley, a star of the U.S. basketball team. He would later become a three-term U.S. Senator from New Jersey. The two athletes talked politics over dinner every night in the athletes’ dining hall and also became lasting friends. The swimmer told Wilson:

“Who would know that years later he would be in the Senate when I needed his support on two major pieces of legislation – the Amateur Sports Act and Title IX?”

The 1964 Games marked de Varona’s fourth visit to the country. In 1961, on a goodwill tour by high school swimmers, she raced boys in relay races in 25m pools in remote villages surrounded by rice paddies, she told Wilson, noting: “I didn’t lose any of those races.” More significant was the healing that was underway in Japan at the time, part of the experience of an elite athlete that would shape an activist with a passion for social activism and change.

This year finds her among a Who’s Who of Olympic champions, Olympians and their supporters calling for the U.S Senate to back the S2330 Empowering Athletes Act, with no loopholes for for rogues to exploit through organisational and constitutional weakness.

Rule 50 And The Right To Protest

Donna de Varona, a member of the IOC women and sport commission, spoke to Wilson as protests rolled across the United States and beyond following the death of George Floyd under the knee of a policeman in Minneapolis. The Black Lives Matter movement was picked up by athletes the world over as an example of an issue they may wish to protest about in peaceful fashion at the very moment of maximum publicity: during an Olympic Games.

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) is considering changes to the Olympic Charter and has consulted – through athlete representatives – athletes to gauge what forms of protest might be acceptable under Rule 50.

De Varona has long expressed the belief that Olympic athletes should follow their conscience and speak out in interviews and be active on social media on issues that affect their welfare and experience as athletes, as well as wider topics where athletes can help steer improvements to the lot and lives of others. On protests at the Olympic Games, she posed a question in her interview with Wilson:

“If I’m on the podium and someone demonstrates for a cause, is that person not only hijacking my moment but, without my agreement, including me in his or her campaign?”

Mack Horton, left, keeps his distance to Sun Yang for the photo-op with bronze medallist Gabriele Detti after medals in the 400m free at world titles in Gwangju … podium protests followed after Sun Yang’s latest brush with anti-doping authorities – Photo Courtesy: Patrick B. Kraemer

Good question. It cuts to the very heart of the podium protests against the presence of Sun Yang by Mack Horton and Duncan Scott at World Championships in Gwangju. Given that no authority had worked fast enough to present Sun from racing, Horton and Scott wanted to make their point peacefully – and did so, by refusing to pose with Sun for podium photos. As de Varona put it, they felt that he would be ‘hijacking their moment’ not only by taking a colour of medal that might have been theirs but by being there beside them forever in the photographic record of the ‘stolen’ moment.

De Varona noted the need, however, for a framework of what is allowable, when and in what circumstances:

“Athletes are not alone up there on the podium if they choose to protest. If they protest, everyone could protest. You could have three different and perhaps adversarial protests taking place on the podium at the same time.”

She was working for ABC as a commentator at Mexico 1968 when American sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos gave raised-fist salutes on the medal podium. Lambasted back then, they are lauded now. De Varona recalled:

“During that time African-American athletes, much less any athlete, had no voice, no representation with any power structure within or outside of sport. I supported Tommie Smith and John Carlos then. Their peaceful demonstration resonated globally.”

Her suggestion to the IOC is this: provide a place in the Olympic Village where athletes can convene to share and express the views – and those discussions could then be broadcast on the Olympic Channel, where further discussion could take place. She told Wilson:

“Bottom line, there would be no Olympics without the athletes. I have always felt that by competing in the Olympics athletes are ambassadors for inclusion, diversity, peace and understanding. With the tremendous pressures and burdens weighing on the movement, we must all come together to find solutions.”

Rare in the Olympic Movement, Donna de Varona has found a way of navigating the fine line between expressing free, independent thought, including stinging criticism and even legal challenge, and diplomacy when steering broadcasters and governors down better pathways on issues of gender discrimination, athlete representation and much else.

Donna de Varona – Career In Brief

- First World Record and Olympic selection in 1960, ahead 13

- Olympic gold, 400m medley and 4x100m freestyle, Tokyo 1964

- One of the most photographed women swimmers in history, de Varona appeared on the covers of Life, Time, the Evening Post and Sports Illustrated (twice).

- After the Olympics, aged 17, she retired from competitive swimming, had no college scholarship to turn to because there were none for women back then, and entered the male-dominated world of sports broadcasting.

- Since then, she has covered 18 winter and summer Olympic Games and won an Emmy and two Gracies for broadcasting.

- Joined Billie Jean King in establishing the The Women’s Sport Foundation in the 1970s. She served as the first President (1979–1984) and subsequently, became the Chairman and Honorary Trustee for the Foundation.

- Inducted to the International Swimming Hall of Fame as an “Honor Swimmer” in 1969.

- Worked as a consultant to the U.S. Senate to help with the passage of the 1978 Amateur Sports Act, which restructured how Olympic sports are governed in the United States.

- Worked with the U.S. Senate to promote and safeguard Title IX of the Equal Education Amendments Act.

- In 2004, de Varona was inducted into the Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca Falls, New York.

- De Varona’s name is synonymous with strong women’s leadership “strong female”, her involvement in legislations protecting women from gender discrimination have played a significant role in the development of women swimmers, while her advocacy for exercise rippled out to benefits well beyond the pool.

- In 2001 she was awarded the International Swimming Hall of Fame’s Al Schoenfield Media Award.

Donna de Varona – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

In 2007, when the International Swimming Hall of Fame celebrated “100 Years of Women In Swimming”, de Varona, a member of the ISHOF Board, spoke eloquently about the need to keep aquatics history alive. This author was there to hear her speak and here are the beautiful words she spoke:

“100 years of women in swimming. Our history is rich not only for the world records and Olympic medals won but for the men and women who have through their dedication inspired excellence, forged social change, fought for fairness, and created a network of individuals worldwide who are dedicated to making a difference in a world constantly seeking common ground.

“Time, place and circumstance are the gifts to our talents. Great coaching and the opportunity to share the water with others who are as passionate and dedicated has made water sports a cornerstone for all the world and especially the Olympics. NBC would have a very difficult time with those ratings if the Games didn’t start out with swimming.

“Those of us who have made it to the top of the victory stand know that we didn’t do it alone. A rival is just as important as a coach. However, when the fierce days of competition are over, it is the friendships forged through mutual respect that count the most.”

De Varona paid homage to “all our athletes who are here to breath new life into a Hall of Fame tradition that cannot be lost – so play it forward everybody”.

Tokyo 1964, Career Highlights, Funny Stories & Advocacy For Women & Fair Play

Recalling Tokyo 1964 in October 2014, 50 years on from her Olympic triumphs, Donna De Varona told her story in the following videos, including how she (unwittingly but perhaps not) psyched out the opposition in the call room by telling them that she would false start (in the days before instant DQ) to help her settle and ‘acclimatise’, and how she managed to get on the 4x100m free relay for the final despite not having raced the 100m at Trials:

Tokyo 1964: “It was like it was yesterday” – Donna DeVarona

When De Varona returned from Tokyo 1964, she watched triple-champion teammate Don Schollander go off to college on a scholarship. That pathway was not open to her, was not open to any women athletes. The Women’s Sports Foundation was formed as a result and the movement for change was underway. Here’s De Varona talking through that and Title 9 during the 1984 Olympic Games (video quality: wobbly):

A rare video at ISHOF captures one of Donna de Varona’s 18 World records or ‘bests’ (including yards swims):

This year, De Varona is the voice of ISHOF’s “One in a Thousand” appeal as the hall of Fame gets set for the next, thrilling, chapter in its history as the home of swimming history:

My father volunteered as a timer for the 1964 US Olympic swimming trials held at Astoria pool. I was there everyday. I was 12 years old and had my program signed by Donna, Don Scholander, Roy Sari and many others including Johnny Weissmiller and Buster Krab. Unfortunately my Mom threw it out while cleaning the basement one day.

Beautiful!

I remember her on tv – very pretty and up beat

Met her and Don Scholander many times in the Early 60’s. Was an upcoming age group swimmer at that time

And she had to retire from swimming at the age of 17 because there were no opportunities for women to continue their swimming in college.

Later, she went on to establish (with Billie Jean King) the Women’s Sports Foundation, and served as its first president, then later a chairwoman and honorary trustee.

Diane Pavelin indeed- all in the article ??

Swimming World I couldn’t get the article to open, so I didn’t see it.

How odd. Let us know if you still can’t get to it. Many thanks, Diane.

There’s another young lady that at a young age broke a world record. Patty Carretto. She had just turned 13 a couple of months before and lowered the 800 meter free in 1964. Had that been in the Olympics 64 Tokyo she may have well been the youngest.

Dona, we will have a drink of Champagne to that memory!

A real lifetime champion, then, now and forever!