Don Lemieux on Coaching Samantha Arsenault to the Olympics

By Brie Harnden, Swimming World College Intern.

Every four years, the finest athletes from 206 countries compete at the Olympic Games. They are celebrated for their abilities on the world’s largest stage. The focus is usually on the current experience: the thrill of Olympic village, the pride of representing one’s country, and showcasing incredible strength and skill.

Often overlooked is the lengthy process necessary to reach this level.

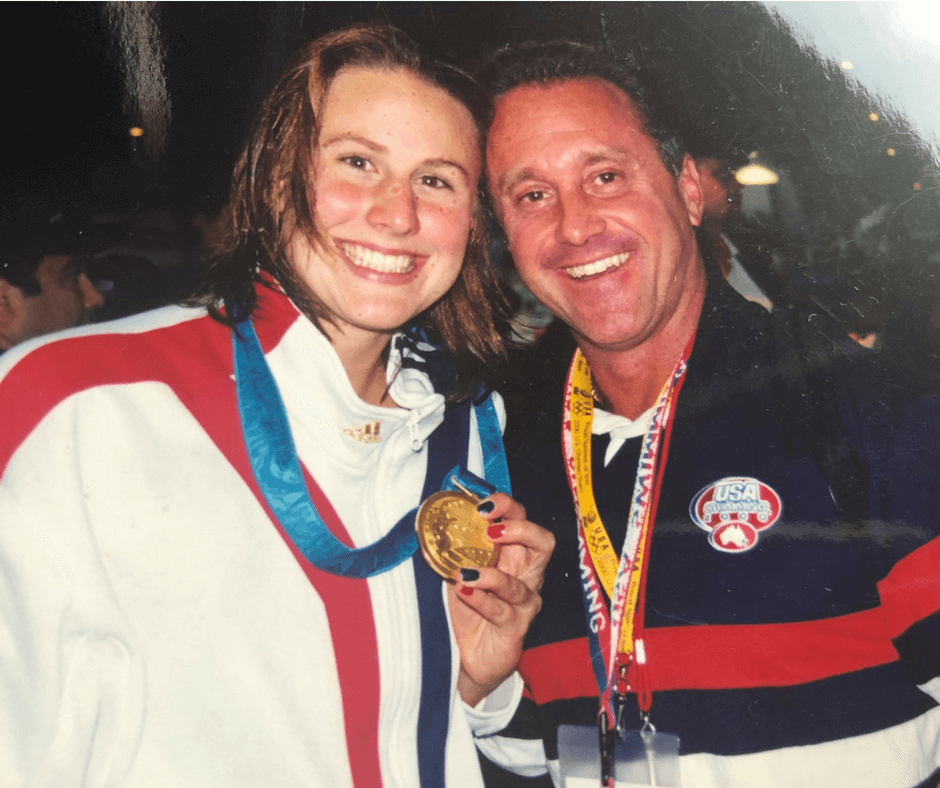

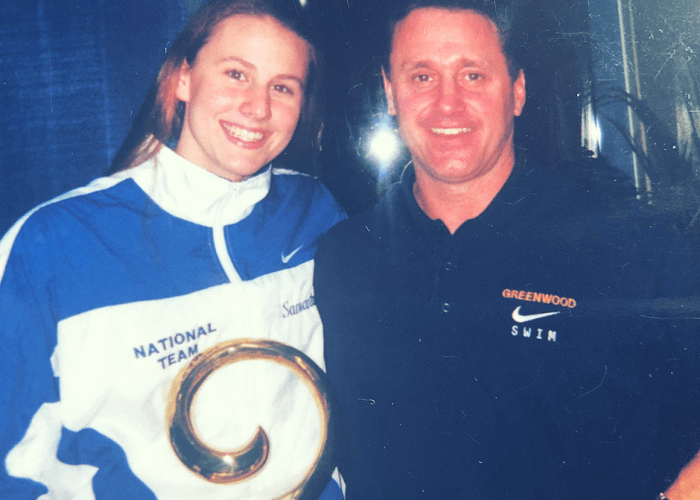

Don Lemieux, head coach of Greenwood Swimming for over three decades, has experienced the intensity of this process firsthand. In 2000, he coached 18-year-old Samantha Arsenault to the pinnacle of swimming – an Olympic gold medal. He reflects on the Sydney Games but spends much more time dwelling on the two years leading up to the meet.

Photo Courtesy: Samantha Livingstone

Following the Plan

As Lemieux looks back on this journey, he stresses the importance of making a plan and following it. He knew that Arsenault had rapidly progressed through 1998 and potentially had a shot at making the Olympic team. Before her physical abilities could be tested, it was crucial that her mental state was sound. The teenager and coach needed to have mutual trust and confidence in this goal; they would either both be completely invested or they would not even attempt to achieve it. Arsenault’s maturity, work ethic, and detail-oriented mindset made her the perfect candidate.

They talked over lunch and made a decision – they were going to go for it.

The following year was a whirlwind of training hard and racing fast. Arsenault continued improving in the water, getting stronger on land, and eating clean in order to give herself in the best opportunity. This schedule of training was created to develop Arsenault into one of the top 200 freestylers in the country and perhaps the world. Regardless of practice intensity or dryland work, Arsenault was expected to travel to meets like US Nationals and the US Open and swim fast.

Photo Courtesy: Samantha Livingstone

Turning Points

Lemieux illustrated some of the turning points of this training plan that ultimately better prepared Arsenault to peak in the late summer of 2000. These moments each individually helped her progress even further.

First, in Italy at a World Cup stop, the Massachusetts coach-swimmer duo arrived to find an unseemly environment. Spectators could smoke indoors, and the pool was poorly lit. Arsenault focused on these distractions and barely snuck in for a bronze medal in the 200 free SCM. From there, they flew to another meet Paris, where Arsenault learned to ignore external factors and won gold the same event – just off the American record. This first turning point in the journey to Sydney was all mental.

Photo Courtesy: Samantha Livingstone

The day after the meet ended, Arsenault and Olympic legend Natalie Coughlin teamed up to complete one of Lemieux’s workouts before flying home. This practice unexpectedly acted as another turning point for Arsenault. “It was hard,” Coach Lemieux recalls with a laugh. “They were going back and forth for probably two and half hours.”

Arsenault found herself challenged swimming next to a historically tough trainer, which fueled her competitive drive even more. She also felt confident – here she was, keeping up with Coughlin! Lemieux remembers a switch in Arsenault’s confidence. She had been committed to the process before, but this increase in confidence took her to another level.

The Ultimate Test

When the Olympic Trials rolled around in August of 2000, Arsenault was ready, and she and Lemieux both knew it. “She cruised prelims, and I mean she cruised,” Lemieux recalls. Her 2:00.0 swim had never felt so easy or smooth. She entered and exited semi-finals as the top seed after another 2:00 easy-speed swim.

The next night for finals, Lemieux believed she would do something “very special.” They had not discussed her times at all during the meet: not during pace warm up, not after prelims, and not after semis. Lemieux didn’t want to ballpark or limit what he thought she was going to do.

Photo Courtesy: Samantha Livingstone

At the 50 meter mark, Lemieux put his watch down. “It’s over,” he told the other coaches standing near him. Arsenault had gone out under world record pace. He had never seen her stroke look so choppy and forced before. She was kicking hard, swimming at 100 tempo. The coaches excitedly misunderstood him, mistaking his disappointment for celebration. “You don’t understand,” he tried explaining. “Her stroke never looks like that. She’s not going to win. That’s not what we worked on.”

Arsenault finished third.

Arsenault became a U.S. Olympian in the 200 freestyle as a relay swimmer. Heartbroken, elated, frustrated, and overwhelmed, Arsenault had made the team. She would not race for an individual title, despite her promise and high performance in the 200 free; however, she would be representing her country at the Olympics, and she was determined to do her job on the relay.

Arsenault and her teammates did their job spectacularly, capturing the gold medal in the 800 freestyle relay and setting the Olympic Record, and Lemieux was there to see it happen. It may not have been the envisioned outcome of the training plan, but Lemieux coached Arsenault to an Olympic gold medal.

An Olympic Champion

Photo Courtesy: Samantha Livingstone

To this day, Lemieux remembers the heartbreak of seeing the number three next to Arsenault’s name on the scoreboard, though he admits if he could go back in time, he’s not sure if he would change anything. Becoming an Olympian is one of the most significant accomplishments in the world of athletics, and Arsenault made the most of her opportunity to represent the USA. Along with Diana Munz, Lindsay Benko, and Jenny Thompson, she became an Olympic champion and Olympic record holder.

Becoming an Olympian is an incredible feat that usually comes with unique, inspiring backstories. Coaching an Olympian is a more mysterious experience. The coach is not in the spotlight like the athlete. Of course, the athlete is responsible for doing the work, but the coach is the one who gives the opportunities and tools for success in the first place. Lemieux’s experience of coaching Arsenault to an Olympic gold demonstrates the best of coach-athlete relationships: mutual trust and confidence.

All commentaries are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Swimming World Magazine nor its staff.