Diabetes Didn’t Stop Grayden Reynolds From Fulfilling His Potential; It’s What Got Him There

Diabetes Didn’t Stop Grayden Reynolds From Fulfilling His Potential; It’s What Got Him There

On the surface, Grayden Reynolds, a junior on USC’s perennial national championship-contending water polo team, is an enigma. His role on the team is a cross between Tim Riggins and the Dos Equis man. Even before he could legally buy alcohol just one month ago, at 6-3, 250 pounds, with a thick, dark beard and unruly hair, he had an easier time passing for 28 than he did for his true age.

From Bakersfield, Calif., built more for the defensive line than anything remotely aquatic, living with diabetes and having faced more hardship than the average USC athlete, or USC student in general, Reynolds is an unlikely character to turn out as one of the best water polo players in the nation.

Photo Courtesy: Jill Burke

Bakersfield is a big, small town. The kind of place that people may leave but often come back to. Think: Pickup trucks, oil rigs and roadside eateries with names like “Country Boy Drive-In” that sell $3 burgers. Aside from the palm trees sprinkled in, if you were dropped there and told you were in Oklahoma, you’d believe it.

Bakersfield is often referred to as “Nashville West.” It makes sense. It’s the kind of All-American town they write songs about. Reynolds’ favorite spot in town? A semi-abandoned air strip, a slab of pavement that he and his friends frequent for bonfires and dancing after dark. There’s a Jordan Davis song about something just like it.

The point is that while there are plenty of places in the United States just like Bakersfield, it’s not exactly water polo country.

Reynolds and his dad joke that the other USC boys played three sports growing up: They surfed, they swam, they played water polo.

It’s not hard to spot the juxtaposition between the teammates who grew up in California’s beach cities, and Reynolds, who grew up in the desert and never had formal swimming training. Other USC water polo players drive 4Runners and hand-me-down Land Rovers with surf board tails hanging out the back window. Reynolds drives a little white sedan with two cowboy hats displayed on the back dash.

“I’m from a town where I’m hardly ever in the water,” Reynolds said. “These guys are in the water 364 days a year because they took a one-day rest to praise the Lord on Christmas.”

He wears cowboy boots unironically to Rock & Reilly’s, a popular USC watering hole across the street from campus in Los Angeles. He has a slight drawl that’s especially noticeable when he speaks of his “dawg,” Indy, named after Indian Motorcycle Company. He served as the TA for USC’s ballroom dancing course. He takes his water polo teammates hunting and has helped many of them purchase their first guns. He sits on the porch of his house near campus in a cowboy hat with a pheasant feather on the brim. Many of his most amusing antics cannot be put in print.

He’s the friendly giant of the neighborhood, greeting anyone and everyone who walks by. He’s one of those people who is so comfortable being himself that he makes everyone around him feel comfortable enough to be themselves.

He’s the one his neighbors call when their faucet breaks. He may not know how to fix it or how to build it, but he’ll figure it out. As past coaches have put it, he’s from a white collar family with a blue collar work ethic.

A self-proclaimed redneck, he certainly seems like one in Los Angeles. But put him in Bakersfield for an afternoon, and there’s something city about him. Not in a tangible way, in a larger-than-life kind of way.

He’s somewhat of a hometown hero. He teaches dancing lessons, often taking his students out for a night of practice at Buck Owens’ Crystal Palace, a live country music bar. There, a sweet older woman named Rosa swoons over him as Reynolds twirls her around the dance floor. It’s where he met Ty, a 16-year-old who he’s taken under his wing, teaching him things like how to get by in school and to hold the door for his sister.

Walking through Hodel’s Country Dining, a buffet in Bakersfield that serves fried steak, jello squares, and mayo based salads (“big people food,” he calls it), all eyes are subtly on him. He walks with a type of confidence that most 21-year-olds don’t have, because most 21-year olds haven’t been through what he’s been through.

Before he even reached double digits in age, he’d had nose surgery, sustained pneumonia too many times to count and slept on an air mattress in his grandparents’ house for five months following the 2008 recession. Still in elementary school, Reynolds had a benign tumor that covered a quarter of his back. After it was removed in fourth grade, he had a drainage tube attached to his back for four months. Year after year growing up, Reynolds braced himself for the next inevitable health issue.

“Everyone has their thing,” Jill Reynolds, Grayden’s mother said. “He just has a few things.”

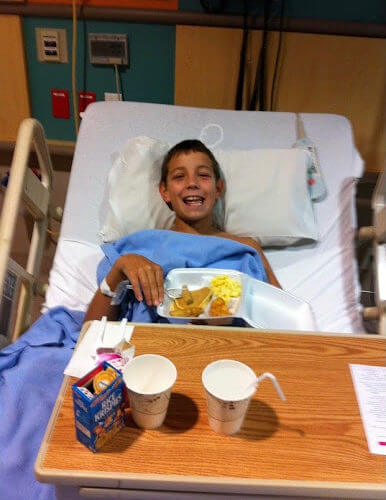

Photo Courtesy: Jill Reynolds

The granddaddy of his extensive list of health complications came just one week before starting fifth grade. On a family backpacking trip, Reynolds could hardly walk after the two mile mark, even after handing off his pack to his dad. After passing out while wakeboarding on the lake the following day, his parents took him to the nearest urgent care, where he was diagnosed with type 1 diabetes and airlifted to Valley Children’s Hospital in Modera County.

There, doctors wouldn’t let him sleep for nearly 48 hours. If he’d gone to bed, he likely would have never woken up.

From then on, Reynolds’ life was never the same. He was in and out of doctors’ offices and had no choice but to overcome his fear of needles to shoot himself with insulin several times per day.

When asked if growing up in hospitals and doctors’ offices made him sad, Reynolds responded that he was just sad when he couldn’t make it into school for the class Christmas party.

Rather than feeling sorry for himself, he took his diagnosis in stride, even doing a science fair project on the effects of video games on blood sugar, using himself as his own lab rat. Reynolds laughs as he recalls how in middle school he’d sometimes use “blood sugar issues” as an excuse to get out of class.

Surprisingly, it wasn’t until after he became diabetic that Reynolds really got into sports, he said. One doctor was particularly inspiring and after telling her that he was interested in sports, she came back to him with about 40 articles about diabetics who play sports collegiately or professionally.

That lit a fire under him. What many might perceive as a grave disadvantage was actually a huge motivator. Without a diabetes diagnosis, Reynolds would not have been so hell bent on beating the odds. He set his sights on playing water polo at USC, a perennially national championship-contending team.

Although his high school in Bakersfield didn’t even have a water polo team, Reynolds played on the one club team in the area. He credits making it onto the USC team to his dad, who drove him to every single USC home game, plus plenty of away games, his junior year of high school to get face time with the coaches. Ultimately, USC had room for him in their 2018 recruiting class but not 2019, so Reynolds graduated high school early and came to L.A.

At practice freshman year, Reynolds’ teammates (some of whom are Olympians) would talk strategy in the pool. When they asked Reynolds what his coaches had taught him growing up, he responded that he’d simply been told “Grayden, put the ball in the f*cking net.” It wasn’t until he got to USC that he learned the technical side of the game. Imagine that. Making it onto one of the best water polo teams in the world, and then learning how to truly play.

Photo Courtesy: John McGillen/USC Athletics

But that’s precisely what makes Reynolds great. He is a prime example that you can be successful at something without making it your entire life. In a world that preaches consistency as the driver of all things good, it’s actually inconsistency that has brought him to where he is today. Playing multiple sports, having multiple interests, having multiple interruptions to his playing career due to illness. It makes him unpredictable. Water polo players aren’t used to encountering the force of a football player in the water, nor the brashness and fearlessness of a guy who has been in multiple motorcycle wrecks. He is inconsistent, but intentional in how he goes about life. A delicate balance.

Last year, Reynolds was sidelined due to concerns from the athletic department surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic and his pre-existing medical condition. This summer, Reynolds is back in the practice pool for the first time in over a year. Ready to win his spot back.

Once again, diabetes held him back, but not for long. And also once again, proving himself not easily defeated will be his biggest motivator.

The chip on his shoulder that is diabetes has actually propelled Reynolds to where he is now. To anyone who has been diagnosed with diabetes like he was 11 years ago, Reynolds shows that while the disease is a disability, it doesn’t have to be a disadvantage. In fact, quite the opposite.

Jill Burke is a multimedia journalist who covers sports, travel and lifestyle. She enjoys “taking the helmet off” of athletes and showing who they are beyond their sport.