College Swimmers Now Profiting Off Their NIL Rights? Good For Them

College Swimmers Now Profiting Off Their NIL Rights? Good For Them

Generations of star swimmers returned from amazing performances at Olympics with a choice: take the money they earned and capitalize on their marketability, at a premium immediately after the Games, or return for another season or more in college swimming, the exciting team-first format that every participant, elite Olympic hopeful or far from that level, cherishes. Almost all choose the college route, delaying their entry to the professional level and losing tens of thousands, hundreds of thousands or, in some cases, millions of dollars.

Now, swimmers no longer have to make that choice. Thanks to NCAA rule changes that allow athletes to profit from their name, image and likeness (NIL) rights, swimmers can earn prize money and have sponsorships while maintaining their NCAA eligibility. Half of the American women’s team from the Tokyo Olympics still has NCAA eligibility, and so do a handful of the U.S. men, while plenty of foreign swimmers such as women’s 100 fly gold medalist Maggie MacNeil and her fellow Canadian Taylor Ruck also compete in the NCAA. Men’s 100 fly third and fourth-place finishers Noe Ponti (Switzerland) and Andrei Minakov (Russia) are both NCAA bound, with plans to compete at NC State and Stanford, respectively.

Now, these women and men can make money. And good for them. Great for them, actually. They deserve to keep the prizes they earn, and they deserve the opportunity to make some cash when their profile is the highest without having to sacrifice all-important NCAA eligibility to do so. Why should swimmers, who have such a narrow window for possible success, be forced to make that choice?

Of course, if some previous Olympians were a bit disappointed about the timing of this change, who could blame them?

Take Missy Franklin, for instance. The Colorado-native was just 17 when she captured the hearts of the United States and won four gold medals and one silver at the 2012 Olympics in London. Franklin was a star, but she chose not to go pro. She wanted to swim in college. Franklin eventually swam for Cal-Berkeley for two seasons, from fall 2013 to spring 2015, before going pro, and she did well financially around and after her second Olympic campaign in 2016, but she never recaptured that level of performance from her high school years.

At the next Olympics, three of the four biggest stars of the U.S. women’s team were collegians: Katie Ledecky, Lilly King and Simone Manuel. So was men’s backstroke gold medalist Ryan Murphy, although he was eligible for just one more year in the college ranks. All turned down the cash, and none wavered in their commitments to their universities, although Ledecky (two years) and Manuel (one year) would eventually forgo some of their NCAA eligibility.

These swimmers did not have the chance to make money. At the same time, Michael Phelps never swam in college because he chose to go pro as a teenager. In the mid-2000s, teenage world champions Katie Hoff and Kate Ziegler made the same call.

Then, in 2019, 17-year-old Regan Smith was forced to consider her options. She had just broken world records in both backstroke event at the World Championships. She looked like a budding star. The movement to change NIL rules had yet to take momentum, and Smith was turning down significant earnings so she could maintain her commitment to Stanford.

As luck would have it, the 2020 Olympics would be delayed one year, just in time for the July 1 rule change that allowed the NIL era to begin in college athletics. And Smith was one of the first to take advantage, inking a deal with Speedo just days after she finished competing in her first Olympics, where she won three medals. Despite earning endorsement dollars, she will still be competing in NCAA swimming.

“It’s definitely something that I will never take for granted, just because I felt both sides, definitely. I’m thankful that I get to have it now and still get to go to college, but I also know two years ago at Worlds, having to turn down the stuff that I earned, that was really tough,” Smith said. “I just want to be extremely thankful that the rule change happened when it did and that I was able to take advantage of it and with a brand that’s been my dream brand to sign with since I started the sport. I just never, ever wanted to take that opportunity for granted.”

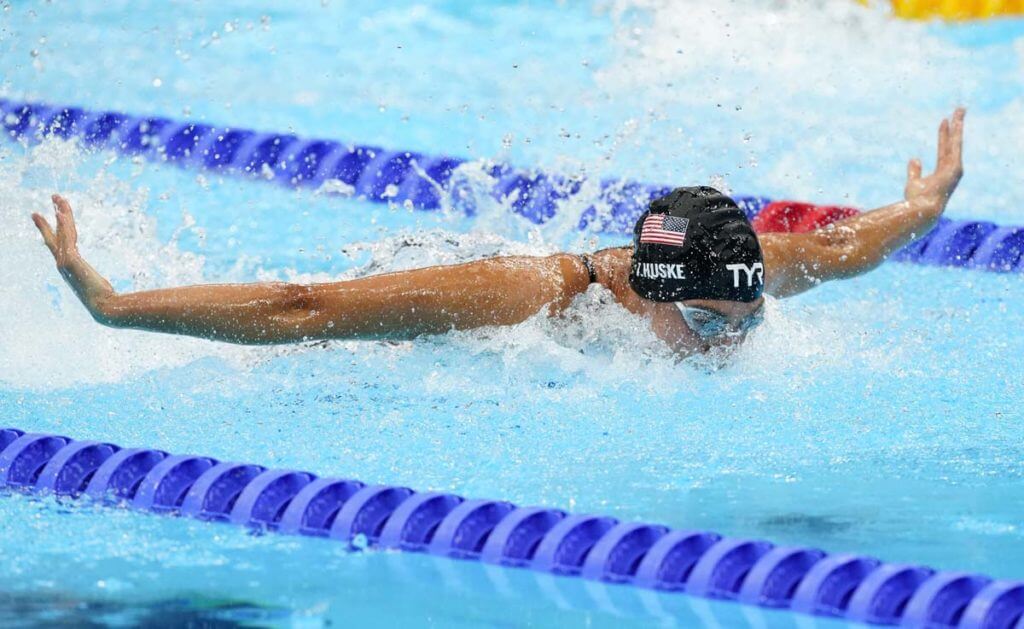

Torri Huske, another U.S. Olympian and also bound for Stanford to begin her college career, went the same route as she signed with TYR while maintaining eligibility. Like Smith, Huske was nothing but grateful about her deal and the luck of her timing to be able to be one of the first sponsored athletes competing in college.

“Obviously, it’s really beneficial to me, so I really am a fan of it. I think that I’m very fortunate,” Huske said. “I don’t know what else to say other than how lucky I am because it’s falling into place at this time. I think it’s really good for the athlete because they’re able to kind of build their image, in a way. I think it’s very lucky on my part that it’s happening right now.”

Few other NCAA-eligible swimmers have announced significant deals, although others have begun working with agents and pursuing marketing opportunities. Incoming NC State freshman David Curtiss partnered with Speedo back in July, and 1500 freestyle silver medalist Erica Sullivan just arrived at Texas and has already signed with an agency. Remember, NIL rights mean more than just traditional apparel sponsorships. Swimmers, even the non-superstars, can promote a product on their Instagram pages and get some cash.

And that’s awesome. All of it. Swimmers deserve the chance to take advantage of their marketability whenever possible.

The New Earning Opportunities

Up until this year, when state legislatures and U.S. Congress put enough pressure on the NCAA to force a rule change, the organization had been dedicated to protecting its version of amateurism. The NCAA and member universities have used the term “student-athletes” for decades, emphasizing that these are students first and athletes second. Of course, the term became something of a misnomer in sports like football and men’s basketball, where schools made millions of dollars off their teams. College sports had become professional in all ways but one, that the athletes got no share of the profits.

Many prominent voices in college athletics have argued that universities should be allowed to pay their athletes, but we are not wading into that discussion. Either way, it’s unlikely any swimmers would be receiving direct university compensation for their abilities anytime soon. But the debate over NIL rights came to the forefront in recent years.

Why shouldn’t superstar players like former Clemson quarterback Trevor Lawrence or former Duke basketball star Zion Williamson be able to make any money off endorsements? Why were less prominent athletes lose their scholarships for earning income totally unrelated to their athletic accomplishments? One such player, Central Florida kicker Donald De La Haye, was declared ineligible for making profits off a YouTube vlog.

And most relevant for this conversation, why should Olympians not have the right to maximize their earning potential when they can, since swimming is really only in the spotlight every four years? Most college football and basketball stars will eventually reach the professional ranks and have plenty of time to make a name for themselves and earn money. For swimmers and other Olympians, that window is extremely limited. Swimming careers are short. This year’s U.S. Olympic team featured just two swimmers older than 27 (Allison Schmitt and Tom Shields), so everyone else was either not in college yet, still in college or within their five years of graduating.

So the life of a professional swimmer is short. New developments like the International Swimming League have expanded swimmers’ earning potential and established a roadmap for a larger population of swimmers to seriously pursue professional opportunities, but this NCAA rule change is still enormously impactful.

Now, swimmers will face less of a decision on whether to stay or go. They can continue racing in college and make some revenue. 100 breaststroke Olympic champion Lydia Jacoby will head to the University of Texas in the fall of 2022, and she has no reason to waver in her commitment since she can profit off her NIL rights. The three University of Virginia IMers who won individual medals in Tokyo, Emma Weyant, Alex Walsh and Kate Douglass, are all in a position to make some money as well.

On the men’s side, there are many less collegians who swam on the U.S. team in Tokyo, but double distance freestyle gold medalist Bobby Finke still has one year left at the University of Florida and possibly two, should he take advantage of the NCAA’s fifth year allowed because of the COVID-19 pandemic. 400 free bronze medalist Kieran Smith is also a rising senior at Florida. Nine of the U.S. men at least have the option of participating in college swimming this year while earning money.

And this new rule could make NCAA swimming a more attractive proposition for international swimmers as well. Certainly, MacNeil is the most prominent non-American in the NCAA right now, and we should expect the rising Michigan senior to take advantage of the rule.

Obviously, the ramifications of this rule change go far, far beyond swimming, but from this narrow lens, no longer having to choose between college swimming and turning professional makes NCAA swimming better.

And for Smith, Huske and any other potential future earners, go right ahead and enjoy the opportunities available. Put money away for the future or splurge now, whatever you choose. That payment is hard-earned and deserved.

Quick scan of the article did not tell me any financial figures.