Celebrating What Would Have Been Doc Counsilman’s 100th Birthday

Legendary coach James “Doc” Counsilman would have celebrated his 100th birthday today, December 28, 2020. The Hall of Fame coach, inducted in 1976, passed away in January 2004 from Parkinson’s Disease. Today, he is still regarded as one of the greatest swim coaches of all-time for his innovative techniques that are still in use today, and for his work in coaching perhaps the greatest training group of all-time at Indiana University in the early 1970s.

Doc Counsilman – 1976 ISHOF Honor Coach

James Counsilman was born December 28, 1920 in Birmingham, Alabama, and grew up and learned to swim in St. Louis, Missouri. He always had an implacable curiosity, and was fascinated by all kinds of swimming motions in nature. As a boy, he loved to watch fish slip through water, and he caught snakes and put them in water to see them swim. The outcome of his interest in animals was that he became a coach/scientist who uncovered many of the secrets of human swimming.

In 1938, at Maplewood, Missouri, Counsilman won his first important swimming race, and caught the attention of Ernst Vornbrock, the coach at the St. Louis Downtown YMCA. Vornbrock came into Counsilman’s life at the right time. His parents had divorced when he was a young boy, and his mother had struggled to support her family alone. Counsilman and his brother Joe were well-behaved, but needed a strong male figure in their lives. Vornbrock saw this, and soon took a keen interest in the young man, in whom he discerned the character and talent that leads to success.

Vornbrock became a big influence in Counsilman’s life; so much so that, 30 years later, Jim was to dedicate his epoch-making book, “The Science of Swimming,” to “My coach, the late Ernst Vornbrock.” He helped Jim to improve his self-image, and discover the potential that lay within him.

Counsilman graduated from high school in 1937 in the middle of the Great Depression and in 1941, he finished second in the 200 breaststroke at the United States national outdoor championships that were held in his hometown of St. Louis. It was at this meet that Counsilman was introduced to Ohio State head coach Mike Peppe, who took an interest in him. Later that year, Counsilman enrolled at Ohio State and won the 220 breaststroke at the 1942 short course nationals in Columbus.

A week before the 1943 Big Tens, Counsilman was called up for military service in the middle of World War II. There is not much written on his military service but it is on record that he served between January and May 1945, where he flew 32 missions as a B-24 bomber pilot and was awarded the Air Medal with Oak Leaf Cluster. While bombing the railroad marshalling yards in Innsbruck, his plane’s landing gear was shot out, and he flew the plane over the Alps to crash land near Zagreb in Yugoslavia, saving the lives of his crew. For his courage Jim Counsilman was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Discharged from the Army Air Corps in August 1945, Doc returned to his studies at Ohio State, and was appointed captain of the championship-winning swimming team in 1946 and 1947. In 1946, he won the Big Ten Conference 200 breaststroke title, and took second in the same event to Indiana’s Charles Keating at NCAAs.

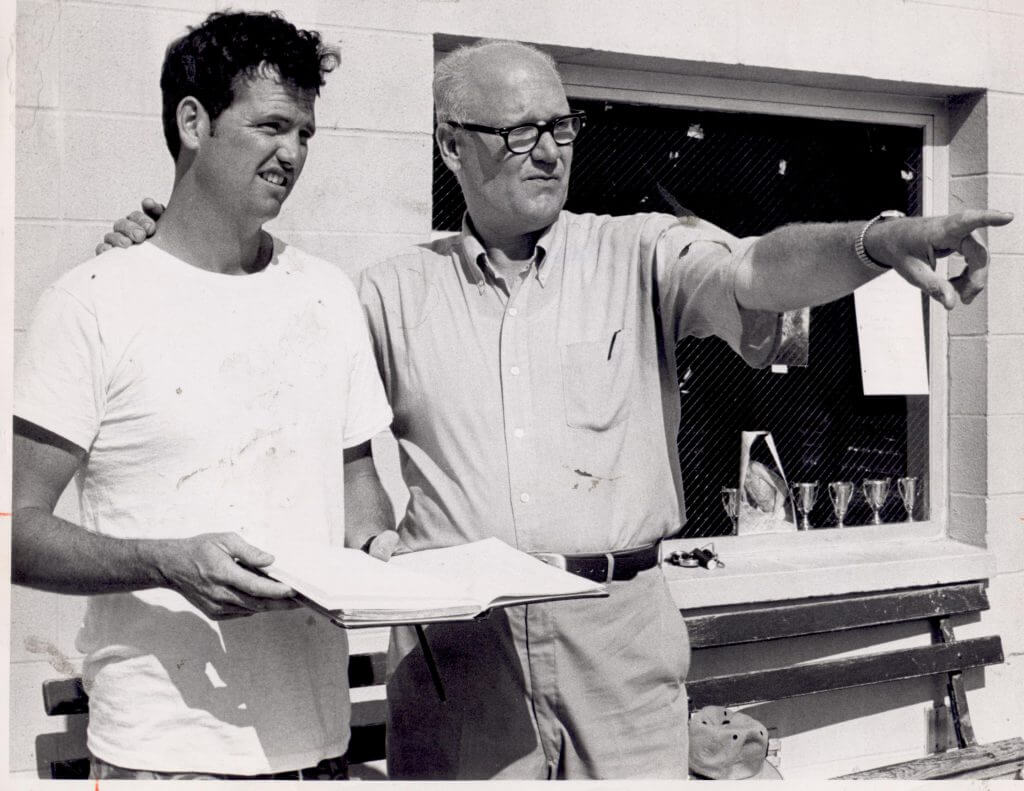

Photo Courtesy: Minor Studio

In those days swimmers were allowed to coach while still competing, and Peppe, impressed by Counsilman’s personality and knowledge, asked him to be his assistant. The former bomber pilot made a strong, mature leader to whom the swimmers reacted with enthusiasm. And he kept a log of every workout, just as he had done in the Air Corps, something he continued throughout his entire coaching career.

Years later, he was to say: “The most valuable research I ever did was contained in the daily training log of every workout I set in my career.”

Counsilman graduated from Ohio State in 1947, then went to the University of Illinois to study for a Master’s degree under Professor Thomas Kirk Cureton, regarded as “the father of swimming research.” Cureton’s pioneering research made prolific contributions to understanding physical fitness and he was one of the first to undertake the physiological measuring of champion swimmers. Cureton was known for his ability to make students think; he challenged them, stimulated their curiosity, and their desire to investigate, saying:”If you end up upsetting tradition, why that’s fine.”

Counsilman’s master’s thesis was on “A Cinematographic Analysis of the Butterfly-Breaststroke,” which included a comparison between the breaststroke whip and wedge kick actions. In this study, he pioneered the use of the motion camera as a scientific instrument for analyzing swimming techniques, and used this technique in the future to study some greats of the sport like Adolph Kiefer and Keith Carter.

After receiving his Master’s from Illinois, he went to the University of Iowa, where he would prepare for his doctoral dissertation, and was an assistant coach for Dave Armbruster in the summer of 1948. It was that summer where Counsilman had a part in coaching Walter Ris to a gold medal in the 100 freestyle at the London Olympic Games.

Ris’ Olympic victory gave Counsilman a great deal of confidence and he completed his doctorate in August, 1951. His dissertation discussed “The Application of Force in Two Types of Crawl Stroke”, and was a continuation of Louis Alley’s early work on the crawl-stroke. He stayed one academic year longer at Iowa, then accepted a post as assistant professor and head swimming coach at The State University of New York (SUNY) at Cortland. It was at Cortland where James became “Doc” after his students informally referred to him as such after Cortland insisted all of its staff be addressed as “Doctor” if they met such requirements.

While at Cortland, Doc spotted a freshman with obvious feel for the water. He had also seen him on the soccer field, and Doc knew that the young man had never swum competitively, but Counsilman told him that, with hard work, he could break world records.

That man was George Breen, who won a bronze medal three years later in the Melbourne Olympic Games in 1956, and broke three world records in distance freestyle. Breen’s unorthodox two-beat crossover crawl kick was criticized by traditionalists who maintained that the ‘correct’ leg action in crawl swimming was the six-beat kick. In 1957, Doc was the first to describe and explain the two-beat crawl, and it became standard for most distance swimmers.

Doc experimented with weight training in the 1950s. He held a landmark symposium of weight training experts at Cortland State in 1954 that helped to dispel the fallacy that weight training made swimmers ‘muscle-bound’. The Australians were making big strides with new training methods, and it was significant that George Breen, a weight-trained athlete, was one of the few non-Australians to challenge them.

By the late 1950s, Doc Counsilman’s reputation as a coach and researcher was well established, and, when Indiana coach Robert Royer became ill and had to retire from his post, Frank McKinney urged the university to hire Doc. Doc thrived on being in the thick of competition, and it was natural that he jumped at the chance to enter the big leagues.

By the late 1950s, Doc Counsilman’s reputation as a coach and researcher was well established, and, when Indiana coach Robert Royer became ill and had to retire from his post, Frank McKinney urged the university to hire Doc. Doc thrived on being in the thick of competition, and it was natural that he jumped at the chance to enter the big leagues.

Doc Counsilman came to Bloomington in 1957, and two outstanding swimmers, Frank McKinney and Frank Brunell, came to swim for Doc. Soon, others followed.

Don Watson, coach of the outstanding Hinsdale High School, who had trained under Doc at Iowa, and was a close friend, encouraged swimmers such as John Kinsella, Scott Cordin, John Murphy, and many others, to go to Indiana.

From Australia came Coach Don Talbot’s outstanding stars, Kevin Berry and Robert Windle, both of Olympic gold medal fame. The momentum was so great that, at the 1964 Olympic Trials, at Flushing Meadows, New York, seven of the eight finalists in the 200 meters breaststroke, led by the great Chet Jastremski, had been coached by Counsilman.

Although barred from competing in the NCAA’s from 1961-1963 because of rule infractions by the university football program, Doc kept morale high and the team continued to compete at a high level in the Big Ten and AAU championships. Ted Stickles broke seven world records in the individual medley event during his career, and, in fact, during those years, it was calculated that Indiana teams could have defeated the rest of the world in a head-to-head competition, as the Indiana men held nine of the 12 individual world records.

Doc Counsilman had an excellent training in the scientific method. His advice to students was: “Outline your topic clearly and discipline yourself to stay within the limits of your subject.” He realized it was important not to become a mere recorder of facts – one should try to penetrate the mystery of their origin.

Doc once said that true understanding in any area of science is always preceded by a series of responses involving three stages:

- Stage One: Curiosity

- Stage Two: Confusion

- Stage Three: Comprehension.

He added that coaches and scientists are constantly challenged by this triad of learning. “The process can be stimulating, but it is often frustrating and annoying because the light at the end of the tunnel often seems very distant.”

Doc said that a study often shows that a certain method is the best, while another study directly contradicts the first one. “The more we discuss the questions, and research them, the further we push ourselves into the second stage, that of confusion. Finally, after dwelling for some time in this stage, we begin to develop some understanding and venture into Stage Three, that of comprehension.”

Doc Counsilman once said: “I doubt that any intelligent scientist/coach believes he ever enters fully into Stage Three on any subject. As he starts to comprehend some concept or principle, he becomes aware of new unanswered questions and the cycle of the triad response begins all over again. The perceptive scientist has come full circle and enters again into Stage One as the cycle repeats itself.”

Doc believed that we keep progressing by evaluating change objectively. He warned: “Don’t paint yourself into a corner; people write something and they are scared to walk away from it.” Doc had an anti-doctrinaire nature which precluded him from swallowing systems whole. He believed that putting methods into neat pigeon holes, to synthesize them, led to “stagnation and not progress.”

Doc contributed to every phase competitive swimming. No phase of the sport escaped his attention and was not significantly improved by his influence. His ground-breaking research covered a wide field. In the area of exercise physiology, and conditioning, he published papers on a wide range of topics: interval training, strength training, isokinetic and biokinetic exercises, hypoxic training, altitude training, and so on and on.

Doc’s first interest had been in kinesiology, the science dealing with the Doc’s contributions to competitive swimming study of body mechanics and the prescription of exercises for developing specific muscle groups. This interest started in high school when he saved up to buy a small “Argus” camera for ten dollars, and asked a school friend to photograph him in various phases of the high jump. Little did he know that this modest start was to grow into a photographic odyssey spanning more than half a century, in which he was to become the consummate artist of underwater photography, who also pioneered the use of the movie camera as a scientific instrument.

Doc once said: “With the wisdom of hindsight, it’s hard to believe that, only forty years ago, coaches didn’t know the exact answers to such questions as to ‘where and how should the hands enter the water?’, ‘should the pull be bent or straight?’, ‘what should be the path of the hands in the stroke?’, and ‘should the stroke be short or long, slow or fast?’

Doc’s early attempts at motion film analysis of swimmers started with the use of an old aircraft movie camera that, according to Doc, ‘looked as if it had been through both World War I and World War II!’ Using outdated film given to him gratis by the university athletic department photographer, he could shoot five or six swimmers in slow motion with each 100 foot roll. The film still cost six dollars per roll to process. Then he would take the film home to study it. In typical painstaking and implacable fashion, Doc gradually solved the problems of underwater photography; light refraction, image distortion, and the use of grids to measure stroke velocity and acceleration.

Last but not least, the big difficulty was the design of an underwater camera housing that was both water-proof, and easily maneuverable. Before perfecting an ideal camera housing, Doc wrote off two expensive movie cameras that were ruined by leakage, and his basement shelves still carry umpteen experimental housings that failed to meet his needs.

The Science of Swimming was published in 1968 and sold 50,000 copies in six languages within two years. Counsilman was awarded the Gold Medallion by the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1990. He was USA Swimming’s head men’s Olympic coach in 1964 and 1976, the latter being regarded as the greatest American men’s swim team in history with Counsilman-coached swimmers Jim Montgomery and Gary Hall winning medals in Montreal.

A great man, who made a positive difference to the lives of many. Respect.

He was not just a great coach but a great man who, by example, pushed all of his swimmers to be good people!

It would be interesting to see a “tree” showing the generations of coaches who were mentored by Doc or by his coaching descendants.

Doc’s book was my first sports “Bible” in 1967, & it was instrumental in becoming a better coach & athlete. Though I was not on the team at IU at that time (you almost had to be a world record holder to make the squad), I got to interact with Doc anyway. He was amazing.

Great article for a great man. Congratulations to the author Andy Ross for this enligtening article that teaches us a lot about science, dedication and healthy role models. Well done Andy!