Celebrating Some Unknown Accomplishments in Black Swimming History

Almost fifteen years ago, my friend Lee Pitts and I created an exhibit at the International Swimming Hall of Fame entitled: “Black Splash: The history of swimming in black and white.” When we made it into a multi-media presentation for an audience, Sabir Muhammad joined us as a presenter along with Charles Chapman, the first African American to conquer the English Channel. It coincided with the early writings of Professors Kevin Dawson and Jeff Wiltse and the exhibit combined much of their research into telling the story. But….that exhibit skipped over a major part of black swimming history that has yet to be told. This is the story of the thriving competitive swimming culture in the black communities during the era of Jim Crow, Separate but Unequal America.

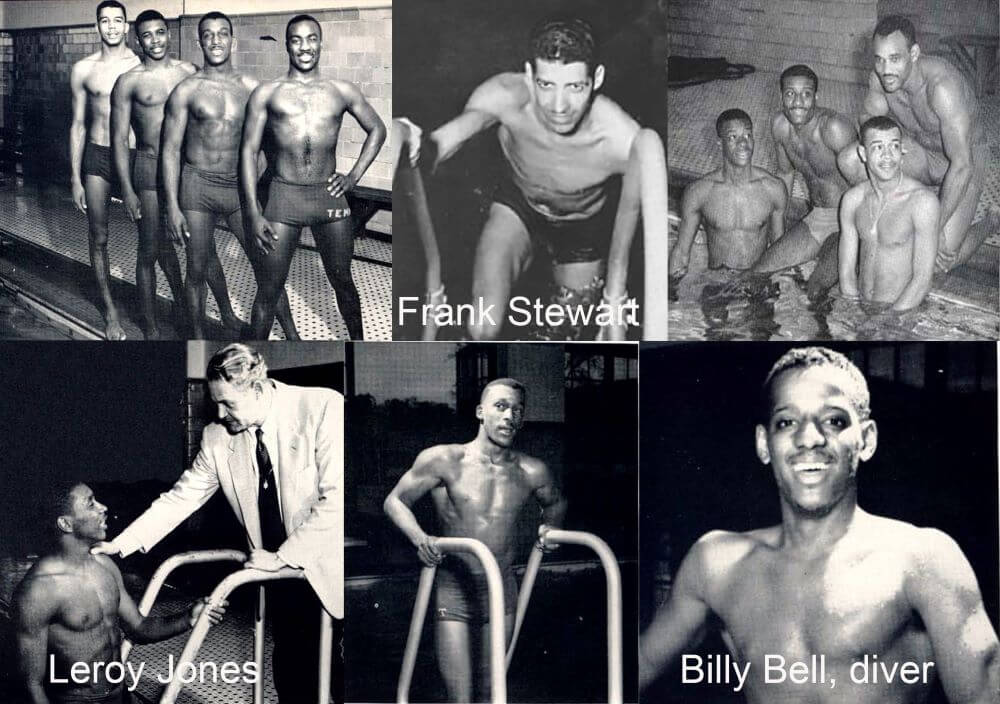

The difficulty in recovering this history is that black competitive swimming was almost totally ignored by the white press and the mainstream leadership of the AAU, YMCA, NCAA and high school swimming. But the internet is still an amazing resource. For example, the images on the photo accompanying this article were retrieved from the Tennessee State University yearbooks that are digitized online. Further research about meet results can be verified through www.newspapers.com, which has a few black papers among their massive archive. And although we’ve only scratched the tip of the iceberg, we are starting to re-rewrite swimming history.

One of the most amazing of facts discovered is that more than 60 years before we thought Cullen Jones became the first African-American world-record holder on a relay team, Frank Stewart was part of one as a member of the Great Lakes Naval Base team. One of his teammates was the great Joe Verdeur, the Michael Phelps of his day. Stewart was considered to be “the greatest negro swimmer of his era (1940’s).” Why had I never heard of him? Other than meet results and that he graduated from Tennessee A&I (an HBCU), we know almost nothing about him.

In 1941, a swimmer from the Brewster Recreation Center, Bucky Washington, won the Michigan AAU 100 freestyle championship at the Brennan Pools in Rouge Park. His time for the event would have been in the top eight of the AAU outdoor nationals that year, had he attended.

Another surprising discovery was Leroy Jones, the great black sprinter of the 1950s. This Jones was the first African American to compete for an HBCU in the NCAA Championships, and was possibly the first African American to do so for any school. While his times during the season in the 50 and 100 were good enough to qualify for the finals, he was off at his two NCAA appearances. I understand he passed away in 2016 in Texas. We need to learn more about him and his experiences swimming in the NCAA Championships.

Stay tuned as we discover more black swimming history – and be a history detective yourself. There was competitive swimming and diving going on in America before the 1960s in nearly every state. Help tell the story!

Awesome!

This is great info to learn about these historic swimmers. I am hopeful that more info is forthcoming from the swimming community at large to help fill in the gaps.

In 1950 my husband, Edward Kirk, was the first black to win a state swim championship in Illinois. While on the swim team for DuSable High School he convinced some of the team to work out at the YMCA, where he worked, as well as at their school.The team succeeded in coming close to being first in high school competition those years. He was the first black to be declared All American Swimmer. He had a swim scholarship to Tennessee State A and I University and competed for them at various colleges. When in the Army in 1957 he was the only black on the team of four that represented the U.S.Armed Forces against seven other countries in a meet in Belgium. He worked for the Chicago Park District for over fifty years, For twenty years he also worked a second full time job at the U.S. Postal Service. He first worked as a Lifeguard in his teens, later as a Natatorium Instructor with a variety of roles including being in charge of the Walter Dyett Swimming Pool, supervising swim staff, coaching swim teams and water polo teams, being Captain at 64th Street beach, supervising summer Park swimming pools, teaching Lifeguarding to hundreds of youth on the South Side of Chicago. Those youth then worked for the summer or full time for the Chicago Park District at pools or at beaches. Ed competed in Masters Swimming meets for many years. After moving to Florida, Coach Ed continued to coach, first at Brandon Swim and Tennis Club, then at high schools, YMCA’s and recreational centers. At BSTC he met Maritza Correia and later watched her win an Olympic medal. After giving up playing the trumpet, Ed’s first love was always swimming. When interviewed by the press he stated, “I will coach until I die.” In a wheelchair, ten days before he died, he coached a ten year old boy how to do flip turns.