Brown’s Felix Mercado and Pomona-Pitzer’s Alex Rodriguez: Growing Water Polo

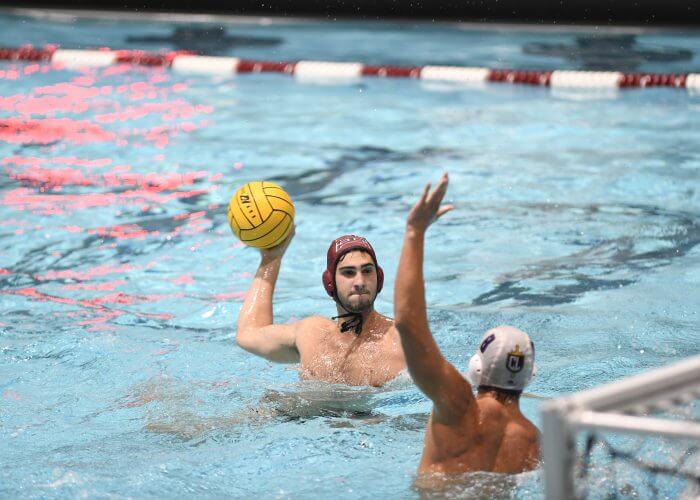

CAMBRIDGE, MA. Last weekend at the 2019 Harvard Invitational men’s water polo tournament, eight Eastern programs descended on Blodgett Pool along with DIII heavyweight Pomona-Pitzer from California. In addition to the compelling action in the pool—seven of the 18 matches were decided by two goals or less—there was opportunity to speak with some of the country’s top coaches, including Brown University’s Felix Mercado and Pomona-Pitzer’s Alex Rodriguez.

[Bears, Crimson Perfect at Harvard Invitational but Sage Hens of Pomona-Pitzer are Big Winners]

Coaching colleagues who give back to the sport in many ways—Mercado is president of the Association of Collegiate Water Polo Coaches (ACAPC) while Rodriguez is an assistant coach for the U.S. senior men’s team—their careers are a testimony to their dedication to polo.

Mercado has coached men’s and women’s polo at Brown since 2007; in 2014 his men’s squad ended a quarter-century of futility, when the Bears qualified for the NCAA tournament for the first time since 1990 As head coach of the Sage Hens, Rodriguez has participated in ten NCAA championships, including three-straight trips to the men’s tournament from 2016 – 18.

Long time friends as well as rivals, Mercado and Rodriquez spoke with Swimming World about the variety of NCAA competition, the challenges and opportunities for schools outside the Mountain Pacific Sports Federation (MPSF), which contains the country’s strongest collegiate programs, and the onset of a DIII National Men’s Championship this December which both coaches believe will have a salutary effect on the sport’s future in America.

– Unlike other invitational tournaments in the East, the Harvard Invite is very competitive—and for Pomona-Pitzer represents an opportunity to experience competition from the other coast.

Alex Rodriguez: Water polo is not as crystal clear as DI, DII or DIII. It’s about resources, funding and location. The Ivies do a great job building competitive program but they don’t have athletic scholarships like other DI programs. They have strict academic standards for admitting athletes that other DI programs don’t have. And you have limitations of training similar to SCIAC (DIII conference). Harvard and Brown are not training year-round like other DI programs are.

Harvard’s Ted Minnis, Pomona-Pitzer’s Alex Rodriguez

For us, I know we’re Division III, but we have resources that other programs don’t. We’re lucky to be in California, the hot bed for water polo. We get some kids that might not look back East. But this is why we’re at Havard, to hopefully help grow the sport. East Coast programs have to travel west for competition. West programs don’t have to travel to fill their schedules.

We love coming out here. I think Teddy Minnis is a professional water polo coach. He’s trying to grow the sport. He’s trying to make it public-friendly, so people want to come watch the games. And I like coming out here and working with high-quality people.

[Winning is Contagious: Ted Minnis and Charlie Owens of Harvard Men’s Water Polo]

In my lifetime, water polo—I graduated in ’98—has not changed a bit. If anything, changes have been a bit negative where it’s not as competitive. This year is the most competition I’ve seen for a national championship since probably my senior year in college. There’s four or five teams that I could see winning a national championship, which I could not have said that any other year before [this].

To me, I don’t look at what Harvard or Brown or Princeton does as in: “Oh, man. They’re up here. They’re D1,” because there are restrictions. To me it’s, if they had scholarships, they were year-round training, that’ll be a whole different conversation. And then I honestly think they would be able to compete with those top three or four teams consistently.

– Dusty Litvak of Princeton has spoken about the divide between what he called “full-time” versus “part-time” polo programs—schools that often have very different academic standards.

Felix Mercado: One thing that has changed the last couple years is coaches have gotten smarter. So, I don’t think year-round training is necessarily an advantage. In many ways, the coaches that don’t have those programs have figured how to create the right culture [to compete], like [when] we beat Pepperdine last year, Harvard beat Cal—and Pomona-Pitzer has beaten UC Irvine.

Year in and year out, it’s about taking down one of the big schools. Just because our programs are limited by our training [calendar] doesn’t mean our athletes are part-time athletes. These athletes are committed to getting in the weight room, into swimming and to doing what they can to make sure they’re getting better.

Harvard’s Dennis Blyashov chose academics at Harvard—and is winning too. Photo Courtesy: Gil Talbot

I think athletes are starting to see: “Hey, we can have balance in our lives. We can go to a really good academic school, still take water polo seriously and not be burnt out when we’re done with it.”

So see the sport growing in a lot of ways, because the coaches are getting better and using the resources the right way, that we’re…. We might not have the resources on the East Coast to compete with the big four. But I think we’ve proven that we can, on the right weekend, take care of business.

– You both know Sean Duncan, the set for Princeton who sat out last season due to a serious injury. His focus is not just what he’s going to do in his last season at Princeton, but on an internship in New York and his future beyond the sport.

Rodriguez: I was reading an article about the NBA—because they’re going away from their one and done [college attendance approach] and going to add a round or two to try to create a G league, a minor league to avoid the college system.

[Water polo] doesn’t have anything [like this]. The European system is what it is, but in America we don’t have a professional league. I don’t know if it’s a smart gamble for an athlete to focus all his effort on playing water polo and then not really have a plan for something after [college]. If you look at it, in my opinion it’s an economical decision. For the NBA, it makes sense to do a G league. It makes sense for the kids to go straight into NBA and make that money because at end of the day they’re going to make enough money that they could go back and pay for their own college if they really need it.

[Princeton’s Sean Duncan & St. Francis’ Will Lapkin: From SoCal to New York City]

But for our sport there has to be a conscious thought of what’s next, what are you doing. We’re a small niche sport so most of us are academic. You don’t have those colleges that maybe endorse football a little bit more, that the standards are really low. You have to do your work [in the pool] and in the classroom.

For us, it’s really exciting. I didn’t really understand it until I came to Pomona-Pitzer. The internships and what the kids are doing after college. Cal Tech is in our conference and it’s always interesting to see those type of kids compete. They’re creating great academic opportunities and [still] they’re playing water polo—but they’re obviously thinking about the future.

– This academic component at both of your schools is extremely challenging— but in general water polo produces smart player who are also smart kids.

Mercado: Yes, smart kids, smart players, but just like Alex said, I don’t think you can discredit state schools. about not having smart kids. My time at MIT, I had someone turn down MIT, got into Long Beach State because Long Beach State’s engineering program was rated high enough that he felt like he wouldn’t take a backseat academically and was able to pay water polo at a different level.

Felix Mercado (center). Photo Courtesy: Brown Athletics

Every state school has a type of program or a department that I’m sure can attract high academic athletes if coaches allow them to do that. Some of my mentors [attended] state schools and are some of the most brilliant people I’ve ever met. So, I’m less likely to say: “Oh, you have to go to an Ivy or high academic school to put yourself in the best position.”

It might be easier because of networking, but ultimately if you want to be the president of the United States, if you want to be a rocket scientist, you can do that wherever you go. You might have to work a little bit harder, but it’s still available to you.

– USA Water Polo, the Collegiate Water Polo Association (CWPA) and the Southern California Intercollegiate Athletic Conference (SCIAC) have created a national DIII championship—which forces programs to choose between the NCAAs and the new tournament.

Rodriguez: I’m pretty black and white when it’s just about the sport. I’m a competitor; I want to win. I want to win a national championship. I won one as a player. If I stay at Pomona-Pitzer, I’d maybe have a chance of winning a Division III National Championship, but you’re always about winning a Division I title.

I have a lot of good friends who coach high school or have left the sport because of the finances or [lack of] opportunity. A lot of coaches like me don’t ever move on because you find a niche school that takes care of you, and you don’t leave.

I don’t know that our sport really respects coaching. Football, you’ll have a coach, he’ll start as an assistant coach. He’ll be a 1A coach and he’ll go up and move up. Urban Meyer started at Bowling Green, moved to Utah. Then he went to Florida and also to Ohio State. There’s a progression from a 1AA school to the top of NCAA football. You don’t really see that in our sport.

– The DIII championship appears to be an ideal way to grow polo…

Rodriguez: Division III-wise, the championship, I think is going to hopefully grow the sport. I haven’t been involved at all, it’s just been all Felix and John Abdou [USAWP], Jenn Dubow [commissioner of the SCIAC] and Dan Sharadin [CWPA commissioner].

[USA Water Polo Division III National Championship Set to Begin in 2019-20]

This is all their work and I 100% guarantee that you’ll see a growth. You’ll see an NCAA Division III Women’s Championship within the next five or six years. With growth, you’ll see more job opportunities, more professionalism from coaches, from the sport, hopefully more focus on the fan experience.

I’m probably more mentality-wise a D1 guy, but first, I’m a teacher, I’m an educator, and I get kids that love to learn water polo. I tell my kids all the time, I’ll ride and die with them because they’re great kids. They want to learn water polo. They want to get better. I really enjoy that. I love coaching—from my best player to my worst—and seeing their growth.

I’m probably more mentality-wise a D1 guy, but first, I’m a teacher, I’m an educator, and I get kids that love to learn water polo. I tell my kids all the time, I’ll ride and die with them because they’re great kids. They want to learn water polo. They want to get better. I really enjoy that. I love coaching—from my best player to my worst—and seeing their growth.

I’m in a really good environment for me, for what I like to do, but the sport needs grow. It needs to become more professional and we have to think about the fan experience. The DIII championship is the first step of many that we need to take.

There’s 1100 colleges and universities [in America]. Can we get a hundred to play polo?

– But, it comes with a price: the SCIAC has to give up it’s spot in the NCAA men’s tournament.

Mercado: That the plan. I want to make sure that we give credit to the USA Water Polo because they’re the ones writing the check. There’s the ACWPC, but USA Water Polo has taken on a big part of this championship.

With Austin College starting in Texas, within the next three, four years, the schools in their conference are looking at this Division III Championship. It’s like, “Oh, there’s a path.” to a national championship. And there is

Everyone has Pac12 envy at [the] DI level. You can only imagine the envy at the DIII level where everyone wants to be like the SCIAC. Out here, NESCAC [New England Small College Athletic Conference], they’re like, “Wait a second, SCIAC gets to put something on there.”

There’s buzz around schools that weren’t interested, now the light at the end of the tunnel just got a little bit bigger.

Also, the Division II conferences, they’re now starting to get organized because they’re like: “Hey, what about us?” And we’re saying, there’s not enough for you guys and we haven’t seen any growth. Now they’re getting more organized and going after their sister school in their conference, saying: “Hey, let’s start water polo so we can.”

I think the only way to protect DI programs is to build the foundation that DIIIs and DIIs are adding to. And eventually I believe we will get to that situation.

Harvard’s Blodgett Pool. Photo Courtesy: M. Randazzo

We have to stop relying on Title IX for adding program and focus on putting out the best product, including being more professional as coaches, continuing to grow our professional development and helping coaches get better, giving them opportunities to take jobs and create new jobs. We are moving in the right direction. This DIII championship, I want it to succeed because I think it’s going to be a big part of that. Going back to the Pomona-Pitzers and the Claremont-Mudd-Scripps and the Whittiers, they still get to compete against the highest level teams and—just like in football—if they beat everybody and they win the DIII championship and they didn’t lose to anyone, why not reward them the coaches association national championship ranking?

And the SCIAC stepped up to the plate. They were like, “Hey, we’ll give up [the automatic qualifier]” because this is important enough to them—even though they know they know they can compete. So I look at the SCIAC and commend them for stepping up because they are the ones that gave up their AQ, at least this year.