Book Review of Jeff Farrell’s “My Olympic Story: Rome 1960”

By Sanford G. Thatcher, Swimming World Contributor

This book might well have been suitably called “A Profile in Courage” or “Find a Way” if those titles had not already been preempted by John F. Kennedy and Diana Nyad, respectively. For this is indeed a story of an athlete who had the “courage” to “find a way” to victory after a stunning and untimely setback that was entirely unexpected.

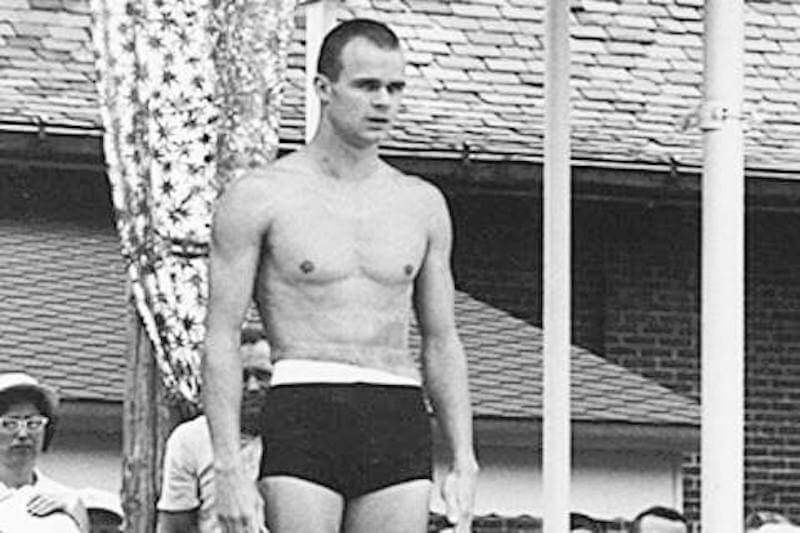

Leading into the Olympic Trials that were to begin on August 2, 1960, there was no faster freestyle sprinter in the world than Jeff Farrell. As he explains in the short Introduction, “In the previous year I had won 7 national and international titles in the 100-meter/yard and 200-meter/220-yard freestyle events, and in the previous 6 months I had set 11 individual national records. No swimmer was considered more likely to qualify for the 1960 American Olympic team that would go to Rome, and I was thought to be an almost certain gold medalist in the 100-meter freestyle.”

But then disaster struck. In the early morning of July 27, Farrell woke up with severe abdominal pains and collapsed in the bathroom of a hotel in Detroit, MI, where he was staying with some other swimmers who had been training with him at Yale under legendary Coach Bob Kiphuth and were getting ready for the Trials. Just twelve hours earlier Farrell had completed a good sprint workout and felt ready for the challenge of making the Olympic team.

This book tells what happened in the ten days following Farrell’s operation to have his appendix removed, a serious surgery that would have put an end to the dreams of most normal athletes—but not Jeff Farrell’s. Through the first ten of the nineteen chapters the story is told by alternating accounts of the days Farrell spent in the hospital recovering with looks back at the road to success Farrell had followed to get him to this peak point in his swimming career. This is a well-chosen structural device to keep the story advancing while filling in details from the past so that readers can understand how Farrell came to have his justified expectations for Olympic glory.

Interestingly, Farrell was not an outstanding swimmer earlier in life. He tried out various team sports but did not find them to his liking. Eventually he focused on swimming and diving as sports in which he felt he might have a chance to excel. But he didn’t begin swimming competitively until he was 10 years old, and he didn’t enter an AAU meet until age 12. His father Felix, who barely knew how to swim himself, became his first coach, relying on a book by Iowa University coach David Armbruster to develop workouts and teach swimming techniques. Later Farrell joined a team at the Wichita Country Club under the guidance of civic leader and former Michigan swimmer Willard Garvey, who started the Wichita Kiwanis Swim Club. But Garvey himself felt Farrell to be “too thin and weak” to excel as a swimmer and recommended that he stick to diving instead. In high school Farrell competed in both diving and swimming, but decided to drop diving in his junior year and concentrate on swimming.

Swimmers in those days had to put up with a lot of adverse conditions that swimmers now would consider barbaric. No one wore goggles, and the chlorine in the water was very strong, leaving swimmers seeing halos around lights after practice. The high school pool had no markings on the bottom or lane lines to keep swimmers separated. There were no flags to warn backstrokers that they were approaching the wall. Training equipment was sparse and primitive. There were no pace clocks, the kickboards were made of wood, and pull buoys did not yet exist, with rubber tubing wrapped around the ankles used instead. The yardage covered in practice was nothing like today’s workouts. Times were measured only to the tenth, nor hundredth, of a second.

Farrell’s first exposure to high-level training came at age 16, between his junior and senior years, when he attended the camp in Canada run by University of Michigan (and 1952 Olympic) coach Matt Mann. Farrell benefited greatly from the refinements of technique he learned from Mann, including the flip turn (which in those days still required touching the wall with the hand as part of the turn). This new knowledge came in handy when he found out that his new coach in his senior year had no background in swimming at all, having previously been assistant coach in football and track and also the cross country coach. Farrell and Bob Timmons nevertheless formed a mutually rewarding partnership, with Farrell contributing his newly acquired expertise in technique and Timmons bringing his passion for sports and some of his dryland training methods from track. Both had success. In his first dual meet of the season Farrell tied the national high school record for the 220-yard freestyle. Ten years later Simmons would tutor a member of his track team named Jim Ryun to become the first high school runner to finish the mile under 4 minutes. In the summer of 1954 Timmons started the Wichita Swim Club. One of Farrell’s young teammates was Richard Quick, who would go on to become a coach at SMU, Iowa State, Auburn, Texas, and Stanford, crediting Timmons with inspiring him to choose coaching as a career.

Despite having tied a national high school record, Farrell did not think of himself as such a good swimmer that he would have a chance of gaining a spot on the roster of the top teams of that era, which included the Big Ten teams of Indiana, Michigan, and Ohio State and the Yale team that had dominated the Ivy League for a long while and had won multiple national championships. Instead, Farrell applied to two second-tier swimming schools, Stanford and Oklahoma. He was accepted at both, but Stanford had only one scholarship to offer and it was not offered to him, so finances obliged him to join the team at Oklahoma instead. As in high school he had the bad luck to have a person hired as swimming coach his freshman year who had no background in swimming and, unlike Timmons, had had no coaching experience in any sport, having been the head trainer for the football team. So in his first year Farrell got no real coaching except from his teammate Graham Johnston, who had been a member of South Africa’s Olympic team in 1952. (Johnston has had great success as a masters swimmer, still going strong today in the 85-89 age group after setting over ninety national and world records across seven age groups. The author of this review has had the pleasure and challenge of competing against him.) Farrell continued to get faster and, with his freshman teammate, diver Dick Kimball, went to New Haven in the spring of 1955 to compete in the AAU indoor nationals, placing fifth in the 220 race. Kimball, an outstanding diver who would go on to become a superstar in the sport, decided to transfer to the University of Michigan, and Farrell was tempted to join him after learning that Oklahoma had hired a basketball coach to be the new swimming coach in his sophomore year. But, as it turned out, Matt Mann, who had been forced to retire from Michigan because of his age (71), prevailed upon Farrell to put in a good word for him with Oklahoma’s athletic director and was hired to become coach at Oklahoma, where he remained until his death eight years later. Under Mann’s guidance Farrell kept improving, but the best he ever was able to accomplish in the NCAA championships was two third places, in the 100 and 220 freestyle. He tried out for the 1956 Olympic team in the 200 but just missed out on qualifying for the relay. At that point he thought his swimming career was over.

After graduation in the spring of 1958 Farrell reported for duty to the Navy, having been in the Navy ROTC program as an undergraduate. His assignment to Pearl Harbor gave him the opportunity to renew acquaintance with the coach of the Hawaii Swim Club, Soichi Sakamoto, whom he had met at the AAU outdoor national meet in Los Angeles in 1955. Sakamoto invited him to train at the Waikiki War Memorial Natatorium and then arranged for him to compete in the summer AAU nationals, where Farrell surprised himself by placing fourth in the 100 freestyle. Still not thinking he would resume his swimming career, at the age of 22 (considered old in the sport then), he nevertheless accepted an invitation from the Navy to join a small group of other Navy swimmers training under Bob Kiphuth at Yale.

And so off to New Haven Farrell went in March 1959. Kiphuth, having recently retired as Yale’s coach after an amazing career starting in 1918 where his teams won 528 dual meets and lost only 12, wanted some way to remain active in the sport, and this Navy program proved ideal for him and for the swimmers taking part in it. Exposed to the best conditioning program he had ever experienced with Kiphuth’s famous dryland training exercises, Farrell needed only a month to get in shape well enough to place third in the 100 at the AAU indoor nationals held at Yale in April with his fastest time ever, 49.5, just slightly behind Lance Larson in 49.2 and Frank Legacki in 49.4 and ahead of 1956 Olympic Champion Jon Henricks. By the time of the outdoor AAU nationals in July, held at Los Altos Hills in California, Farrell had gotten even better, winning both the 100 and 200 in the long-cource events in the times of 56.9 and 2:06.9, his best ever earning him his first gold medals in national competition. This achievement led to his becoming co-captain of the US team (along with George Breen) that traveled to Japan for the international meet held every four years, then the only international competition available besides the Olympics, Pan American Games, and the Maccabiah Games.

Encouraged to believe that he could now compete on an international stage, Farrell tried out for and won a place on the team for the Pan American Games where he set a new Pan Am record in the 100 freestyle in 56.3 and anchored the 400 medley relay to a new Pan Am and American record of 4:14.9. With no major meets on the schedule before the AAU indoor nationals in April 1960, Farrell took the opportunity Kiphuth offered to swim in several special meets at Yale aimed at allowing a handful of top swimmers to set new records. The first week in February saw Farrell doing just that, setting new American records in the 100 freestyle in a 20-yard course (48.3) and in a 25-meter course (54.4). A week later during the annual Yale Winter Carnival he managed to lower the American record in the 100 to 48.4. In the AAU indoor nationals held at Yale, Farrell again broke the American records in the 100 (48.2) and 220 (2:00.2). He followed up these triumphs in an exhibition meet at Yale by finishing the 200-meter freestyle in 1:59.4, becoming the first swimmer to go under 2 minutes. At the outdoor AAU long-course nationals in July he won both the 100 and 200 freestyle events, setting a new American record in the 100 (54.8).

The stage was thus set for the Olympic Trials, with Farrell having every reason to believe that he could make the team and even earn gold medals in Rome. But then came the appendicitis, landing him in the hospital on July 27. The story of the next ten days is gripping. No one gave Farrell much of a chance of even competing, let alone excelling, in the Trials. A key to his recovery, though, was Kiphuth’s knowledge of human anatomy and his recommendation to the surgeon about how to do the operation, separating rather than cutting through the abdominal muscles to get to the appendix. After several days of rest, Farrell ventured into the hospital’s pool for some light exercising. Never relenting in his determination to try making the team, not just for a spot on the relay but also for the 100 freestyle (there not yet being a 50 freestyle event in the Olympics), Farrell worked with Kiphuth and his physicians to get to the point of attempting some sprints in practice. Bandaged in his midriff and not yet being able to do an entry dive aggressively, he did well enough to keep thinking he had a chance. He even turned down an unprecedented offer from the US Olympic Committee, which would have allowed him to bypass the Trials and yet still make the team a week later by participating in a special runoff race. Not only did he not want any special treatment, but he thought it would be highly unfair for another person to be bumped from the team a week later after this runoff race after properly qualifying for it at the Trials.

In the prelims Farrell managed to finish first in his heat with a time of 55.9 and overall qualified second for the evening semi-finals behind only Steve Clark in 55.5. In the semis he went even faster, finishing in 55.6 to gain the top seed in the finals the next day. Thinking about how he had managed to do so well after not practicing for a week, Farrell remembered what Australian swim coach Forbes Carlisle had written about the importance of rest before a major meet, believing too much rest to be better than too much training. Confident that he still had a good chance to place in the top two in the finals and thus make the team as one of the entries in the 100 freestyle, Farrell swam what he thought to be a good race—until the last 15 meters when, inexplicably, he swerved off course and his right hand hit the lane line, throwing off his rhythm just enough that he failed to get to the wall in time. Lance Larson won the event in a speedy 55.0, Bruce Hunter of Harvard was second in 56.0, and Farrell touched in 56.1. It was a crushing disappointment. He briefly considered not trying to make the team for a spot on the relay. Remarkably, in an act of extraordinary generosity, Hunter offered to withdraw, after slipping and breaking his toe, and allow Farrell to take his place in the 100 race, but Farrell declined. Reflecting further on how it had always been his dream just to be on the Olympic team, he regained his composure in time to compete in the 200-meter prelims and semis the next day, qualifying sixth for the finals. In that evening event all he had to do to make the team was to finish in the top six, but he improved to place fourth. When presented with his certificate as a member of the team, Farrell received a standing ovation from the crowd, the first time the presenter, TV and film star Andy Devine (a strong supporter of swimming and the father of two sons who excelled in the sport), said he had ever seen spectators do that at a swimming meet.

All that remained was the Olympics itself. The team, led by Breen and Farrell as co-captains, immediately began training after arriving on August 14. Rome was the last of the old Olympics in some ways and the first of the new in other ways. It was the first to be commercially televised around the world, ensuring it a much bigger audience than the Games had ever had before, but there were only about half as many events as there are today—just eight in swimming, including relays, compared with sixteen in 2012. Farrell watched the 100 freestyle finals, which proved to be the most controversial in the entire Games as American Lance Larson lost out to Australian John Devitt on a judges’ decision even though the timers had all clocked Larson as finishing faster. For the two relays, the 400 medley and 800 freestyle, Farrell was chosen to be the anchor for both, and they were held just an hour apart on September 1. Farrell’s teammates in the medley—Frank McKinney (backstroke), Paul Hait (breaststroke), and Lance Larson (butterfly)—gave Farrell such a big lead that he found himself able to ease up on the last stretch of the race in order to conserve some more energy for the next relay. Even so, the team easily beat the Australians by over six seconds and set Olympic and world records with a time of 4:05.4. (This was the first Olympics in which this relay had been contested, butterfly having become a separate stroke just before the 1956 Olympics, when the medley included only backstroke, breaststroke, and freestyle.) The same happened in the 800 freestyle relay, with the team of George Harrison, Dick Blick, Mike Troy, and Farrell beating the Japanese by three seconds in 8:10.2 for new Olympic and world records.

Again, with two Olympic gold medals in hand, Farrell considered this to be the capstone and end of his swimming career. For his achievements he was given several awards, none more meaningful than the AAU Swimming Award, which he was the first swimmer to win, its having previously been bestowed on coaches, officials, and organizations. He briefly considered coaching as a possible career after spending a summer when he coached teams in Tunisia and Morocco at the behest of the US State Department. He then thought of applying to Yale Law School but ended up instead getting a master’s degree in international relations at Yale, which served him well over the next six years when he worked for CARE and The Asia Foundation in Southeast Asia. He met and married a French-Vietnamese woman in Bangkok and with her ran a clothing business there for the next twelve years as they started a family. They sold the business and moved to Santa Barbara, CA, in 1980 whereupon Farrell got introduced to masters swimming and renewed his love of the sport. Over the next thirty-two years he competed in many masters meets, setting a host of regional, national, and world records in the five-year age groups he passed through, until health problems compelled him to hang up his suit for the last time when he was 74. For his accomplishments Farrell was inducted into the International Swimming Hall of Fame in 1968 and the International Masters Swimming Hall of Fame in 2011.

Anyone who knows what hard work it takes to excel in this sport cannot help being inspired by Farrell’s story, for it epitomizes dedication and perseverance under the most trying of circumstances. An appendectomy would stop a lesser mortal in his track, but Jeff Farrell displayed extraordinary courage and did find a way to win against all odds in the 1960 Olympics and his monumental achievement will not soon be forgotten. This is a book, written in clear and unadorned prose with over fifty illustrations complementing the text, that every competitive swimmer should read, and that should provide inspiration for competitors in all sports.

About the reviewer: Sanford Thatcher began his swimming career at age 5 at a summer camp in Pennsylvania, swam for a prep school in Kingston, PA, and was privileged to join the freshman and later varsity teams at Princeton for four years from 1961 to 1965. A highlight of his time there was Princeton beating Yale for the Kiphuth Trophy in the Easterns in 1962. He took up masters swimming when the Princeton Area Masters group was formed in 1971 and has been competing ever since, currently for the Plano Wetcats and Frisco Amateur Summer Swim Team in North Texas. In May 2015, at his 50th Reunion, he was presented with the 250th Award of the Princeton University Competitive Swimming and Diving Team for “outstanding dedication and commitment” to the program.

Great yarn and I’m sure Jef’ll always believe in his heart of hearts that had he been healthy he would gave beaten eventual Rome 100 free Gold- Medalist John Devitt, who ” stroke” the Gokden from Lance Larson in a very contentious judges’ decision.

But they Matt Biindi’ll alwayscwondervwhetherband if he had finished just a tad differently in the 100 fly @. Seoul would he have be wren Anthony Nesty? And Michael Cavic still probably believes he beat you know who @. Beijing.

Well unless Jeff told you he believed that, it’s simply speculation. And those aren’t apt comparisons anyway; neither Bondi nor Cavic had health issues so both had their chance to apply their skills to challenge directly for the gold and lost. Whether or not Cavic accepted the results of the clocks and the judges is also irrelevant to the case of Jeff Farrell. The point was , Farrell wasn’t the type to let such temporary setbacks derail him, as he showed both at the Olympics and in his successful life and swimming career afterwards. I had a chance to hang out with him at USMS nationals yeas ago and he was a gracious and humble man as well. Congrats Jeff!

Great to read how Jeff maintained the integrity of the selection process that is used in the US. No committee involved like other countries and we have always put forth a full roster that is allowed with out considering how they might finish as other countries do and it is rare when they fill a team. Thanks also to USOC for funding the complete team. Some don’t agree but it is the best way as the record of performance since 1896 shows.