Better With Age: Leanne Smith Eager to Chase More Success in Para Swimming World

Better With Age: Leanne Smith Ready to Chase More Success in Para Swimming World

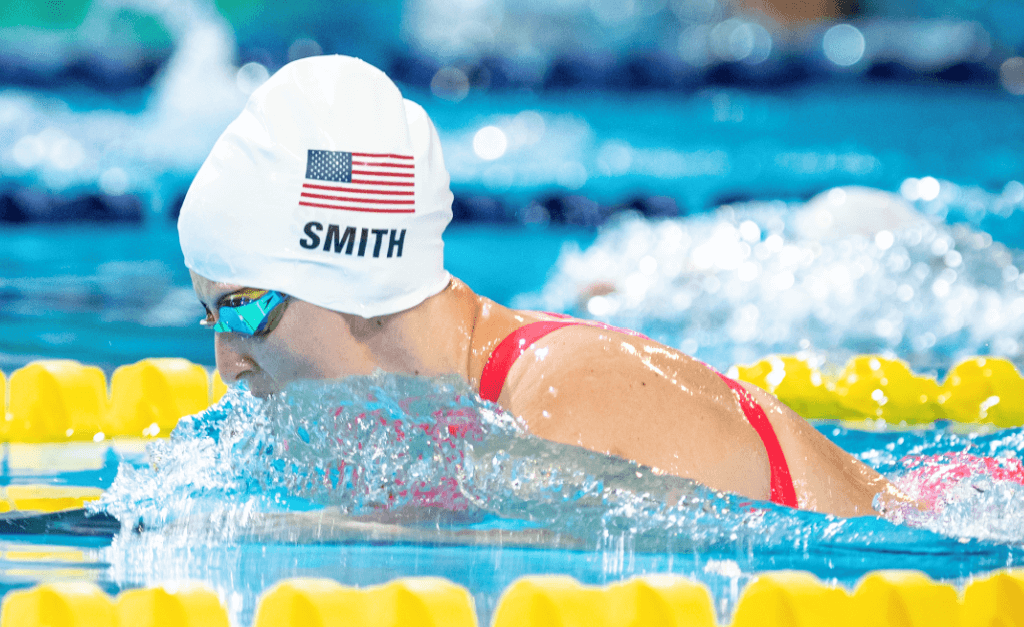

Leanne Smith turned in a career-defining performance at the recent World Para Swimming Championships in Madeira, Portugal, where she won seven gold medals. As a paraswimmer, the 34-year-old now hopes to use her performances in the pool to demonstrate to others what they’re capable of.

With a laugh and a touch of residual pride, Leanne Smith describes it as being dragged to the pool.

She was eight weeks into the latest phase of her rehabilitation plan—in the third year of wrestling with a life-altering neurological muscle condition—when swimming was proposed to her as a therapeutic option. Smith took to the water with a healthy dose of skepticism, unsure if she was getting more out of her first two months in the pool beyond a brief respite from being confined to her wheelchair.

But upon starting swim therapy in 2013, she had apparently shown enough to pique the interest of John Ogden, a coach at the Beverly YMCA in her native Massachusetts, who had experience with paraswimmers. Something about the competitive drive Smith brought to her sessions made Ogden pose the question.

“He approached me and said, ‘What do you think of swimming?,” Smith recalled recently. “And I laughed at him. And he was not kidding. He was very serious about the prospect of it.”

Plenty of factors have conspired to drag Smith away from the pool. But this stroke of luck and insight by Ogden has pushed her insistently toward the water, a drive that has withstood a litany of challenges in the last decade.

Smith is fresh off an outstanding spring, in which the American set four world records and won seven gold medals at the World Para Swimming Championships in Madeira, Portugal, last June—this from an athlete who’s dealt with sabbaticals from swimming, both self-imposed and health-related, yet at age 34 is achieving more than ever.

Her performance also sets a template that Smith hopes to follow for the Paris Paralympics in 2024. It could be a rare opportunity—in a career that has had to adapt to so many external challenges—for Smith to set her own course toward a valedictory Paralympics.

INTO THE POOL

Smith’s journey to a wheelchair—and thus to paraswimming—took nearly two years to diagnose before a career coping with changes in classification and physical ability.

In 2010, Smith experienced facial paralysis and numbness, which required five months of hospitalization to seek a cause. Not until 2012 did she have a concrete diagnosis of why her body was betraying her: dystonia, a rare and degenerative neurological condition that presents itself in a wide range of symptoms, affected areas and levels of disability.

In learning to live with her condition, Smith began swimming in 2013, a way to take stress off her body and get her moving again. It wasn’t a jump she was necessarily eager for—the lack of body control typical of dystonia sparked fear of how her body would react in water. But she progressed from dipping her toes in from the deck to flotation devices to treading water, growing to embrace the unique freedom the water offered.

“I wasn’t confined to my wheelchair,” she says. “And I was going through a period of time where everyone only saw me in a wheelchair, and society puts their own limitations and has their own opinions on what that means. I felt very unseen and just being known as ‘the girl in the wheelchair.’ To detach myself from that felt great, and it was a little bit more of a sense of what my normal was.”

At a certain point, things clicked for Smith. She’d always been a competitor, as a club gymnast who also played softball and soccer in high school, and as a gymnastics instructor at the Y in Beverly when dystonia first struck. (Her pre-paraswimming experience was mostly limited to backyard pools.) “It really doesn’t go away, at least for me it hasn’t,” she says of her fire. “So once I was comfortable in the water, it kind of re-emerged and in my favor.”

Smith started competing quickly. By May of 2013, she’d gotten classified in her first meet and attained a cut for the Can Am Para-Swimming Championships. That December, she swam internationally for the first time for the national team. She also dabbled in sled hockey, making a U.S. developmental team.

Nathan Manley, U.S. Paralympics Swimming’s resident coach, first encountered Smith early in her career, though he wouldn’t work with her regularly until 2016. She was classified in S7 then, and Manley is intrigued to have met the gymnast she was in her past life to draw parallels in her competitive drive. He finds it easy to imagine that tenacity he’s so familiar with being there all along.

“She is really determined to excel in competition,” Manley says. “That is an internal thing for her. Whether it’s in training or whatever, she’s really focused on being the best she can be and working all that out. She believes that applies to kicking everyone else’s butt.”

Had things progressed as planned from that breakthrough 2013, the Paralympics in Rio loomed as the logical next step. That wasn’t the path she was fated for, though.

A MAJOR SETBACK

With just under two years to the Rio Paralympics, Smith endured what she now calls a setback. It seems almost euphemistic to label it so lightly.

Smith began experiencing seizures in August of 2014. She was hospitalized for two months, with more inpatient rehab on top of that. In all, she was unable to train at a significant level for some 14 months. By the time she returned to full training in early 2016, Rio was clearly off the table.

“She’s endured her lot and then some with health challenges, from ending up in this situation where she’s even eligible to be in para sport,” Manley says. “…It is a game to help her be healthy at the right times because it’s not going to be a situation where she can just recover from an injury and be fine. It’s not that kind of path. It’s a constant battle.”

When she returned to competition, her reinvention was more literal than figurative. Changes in her physical ability meant she dropped from S7 to S4 (she’s currently competing in S3, where “S” represents freestyle, backstroke and butterfly strokes, “SB” represents breaststroke and “SM” represents individual medley; the number represents the level of disability, with “1” being the most physcially impaired to “10” having the least amount of physical disability).

In 2017, she committed to chasing the Tokyo Games, relocating to Colorado Springs to train with Manley and many of the nation’s top Paralympic swimmers at the USOPC Training Center.

Smith made her case quickly. She set world records in both the S3 and S4 50 butterfly in Copenhagen in 2017 at the Inaugural World Para Swimming Series. She followed up a taste of the World Championships in 2017 with three gold medals and a silver at 2019 Worlds in London. She started 2020 with a world record in the women’s SB3 100 breaststroke among four American and four Pan-American records at the Jimi Flowers Classic.

A TIME OF UNCERTAINTY

By now, Smith had come to learn not to expect smooth sailing, and 2020 would be no exception. She was in Colorado Springs when that facility closed during the COVID-19 pandemic. A core group—including Jessica Long, Colleen Young and McKenzie Coan—helped each other cope with the uncertainty before and eventual postponement of the Games.

“It was definitely a difficult time to really just sit there and be amongst so many other athletes as well, with so much uncertainty,” she says. “You’re continuing to train, but are you training for this event that is actually going to happen or is it not going to happen? Some days it’s harder to stay motivated in that way, because the extra year is such a long year, and given everything we were going through, you’re obviously much more limited in how you can separate training and having a life outside of training. So it was definitely a difficult time for me.”

Things got more complicated for Smith when the training base closed that summer, which led to a rowing machine mishap requiring emergency abdominal surgery and another two months of rehab.

By the fall, Manley and Smith were playing that familiar game, of trying to avoid catastrophe and will the calendar to the whims of Smith’s condition. They hoped the Tokyo Games would fall on a positive ebb in form. And while the results were certainly respectable—silver in the S3 100 freestyle, fifth in the 150 individual medley and 50 breast, sixth in the 50 backstroke—Smith knew it wasn’t her peak. “We were trying to get her in a space where she’s healthy enough to be capable of what she’s capable of,” is how Manley puts it.

So Smith took time to recover after Tokyo, reassessing her goals over four training-free months. While age is just a number to her—with all the concrete challenges she’s conquered, she doesn’t need to court imagined ones—she had to weigh what more she wanted and what her body could provide against the sense of “unfinished business” from Tokyo. Once 2022 hit and she returned to the water, it clicked just how much more she wanted to be there. She hopes to swim through Paris for one more chance to swim at her peak on the Paralympic stage.

AMONG THE WORLD’S BEST

Madeira showed that when she’s on her game, she’s one of the best in the world. Her seven-gold performance (the SM4 150 IM, SB3 50 breast, S3 50 back, 50 free, 100 free, 200 free and 200 medley relay 20 points) is the most prolific for an American since Long in 2010. She also holds four S3/SM3 world records. She set the 200 free and 150 IM at World Trials in Indianapolis in April, then followed up with the 50 and 100 free in Portugal.

Smith is driven by more than times, though. One of the most salient emotions from those first weeks at the Y, as she hesitantly dangled her toes in the water, was about what the world saw in her. She was grappling with a new identity of being in a wheelchair, knowing she was much more than the limits others placed on her. She’s paid that forward as a swimming instructor in the years since, and she hopes to use her performances in the pool to demonstrate to others what they’re capable of.

“With my performances at Worlds, it just kind of solidified that I’m on the right track with what I’m doing here and that I am not washed up,” she says. “That was definitely a concern I had after Tokyo. It’s just been very reassuring after those two meets that I still have it in me, and I can still continue to get faster even as I get older.”