Athlete Sustainability – Why Do So Many Youngsters Stop Swimming & What Will The Drop Look Like After COVID?

2020s Vision – Athlete Sustainability and Lessons From Sweden That Speak Louder After COVID-19 Lockdown

There was a sobering moment at the World Aquatics Development Conference in Lund back in January when Ulrika Sandmark, performance head coach of Swedish swimming, put a slide up on the board and paused to let the audience soak up the sink in the message on the screen.

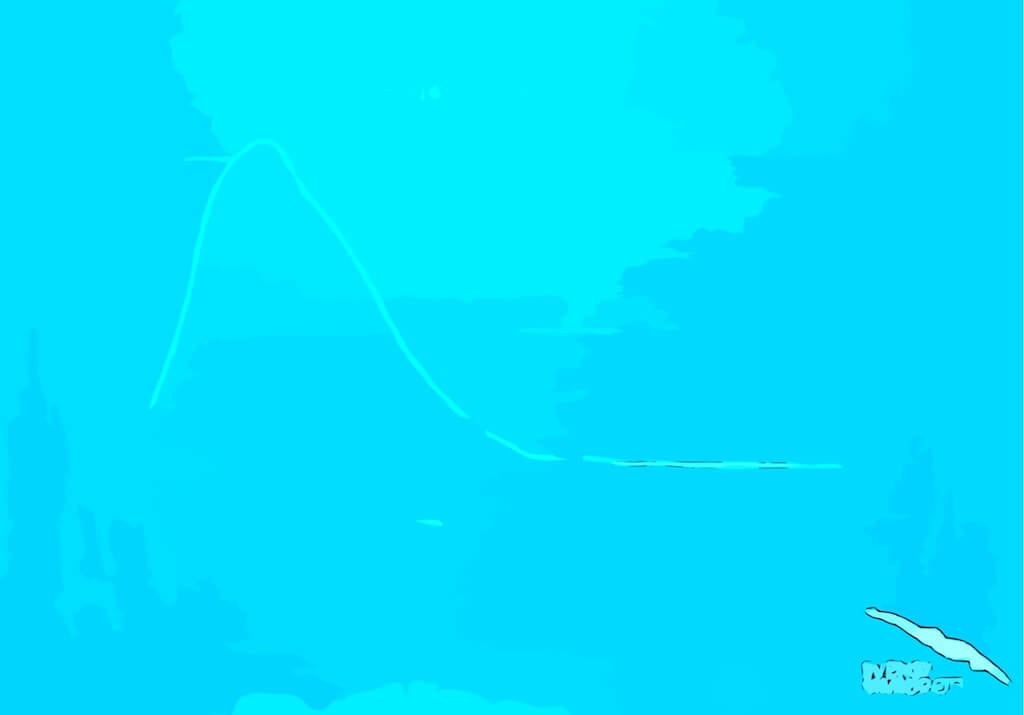

Our main image with this article is an artistic impression of Sandmark’s graphic, using the precise dimensions of the original. The peak of the curve represents the high tide of swimmer numbers by age in Sweden: they are 12 years old. In the year before kids turn teens, Sweden’s birthing pool of talent is a busy, bustling, healthy pool.

Then … the drop in dramatic. The steep loss to swimming happens as children, their parents, families, for whatever reasons, opt out, leave the pool, leave the sport, few ever to return. Swimming becomes holiday fun, perhaps later in life a contributor to fitness but for the sport, the swim club, the feeder programs from which all Olympians flow, the high tide of 8-12 years olds who enter the sport turns to a rock pool when we look at the numbers left by the time the kids are 16-18.

Sandmark’s talk was on “Athlete Sustainability” and it was delivered before any of us knew that COVID-19 would wipe out an entire season and summer of swimming in a global health pandemic that risks turning the wave of lost swimmers at a critical age into a flood, for a variety of reasons.

A distance freestyler in her own day, a coach after that and the head of the program for the past couple of Olympic cycles, Sandmark sums up her approach to swimming excellence when she says: “The athlete in the suit is not the most interesting thing in the picture – we’re interested in the whole person behind it”.

Ulrika Sandmark – Photo Courtesy: Jonathan Näckstrand for the World Aquatic Development Conference

Head coach to one of Sweden’s best swimming clubs, Väsby Simsällskap, between 1996 and 2012, Sandmark took on the top coach job in Sweden in 2013, the season after Sarah Sjöström’s career started to go global in a big way (before 2013, Sjöström’s one medal in global waters was the World 100m butterfly title from Rome 2009, aged 15).

Today, Sjöström’s mother speaks to the theme of talent and athlete sustainability when she tells a Swedish newspaper that many a talent and potential might be lost to sport because there is too much focus on specialisation too early. Her daughter was 10 before she took up swimming. She was 14 when she claimed her first European senior title.

In Lund, Sandmark considered a slide of ‘survivors’, including Therese Alshammar, an athlete and racer well into her 30s after making podiums, Olympic, World and European in her late teens to early 20s, Sjöström and Simon Sjödin, both in the late 20s, Sjöström intending to go on for many a year yet. There was also Ida Marko-Varga, mother of two and an athlete yet, at 35.

Sandmark speaks of late bloomers and notes that the aim of the Swedish program is to ensure that swimmers have a “long career in which they reach their full potential … because that would be out goal as coaches and responsible club leaders.”

She notes conversations she has had with leading swimmers as they ended their careers and addresses her audience:

“Among the things that are important to think about as a coach or a person of responsibility in a club is what we have to do in order to create an environment that would keep the swimmers swimming their whole life and be able to say as they finish their top racing days that they love swimming.

“What things can we do to create strategies before a normative transition to the rest of life. A normative transition is a change that we already know will come but I think we can be much better at planning that moment. In a swimmer’s career there are many transitions: it can be, for instance, when you go from ‘learn-to-swim’ to training or when you go from one school to another, junior to senior; then on to college, university. I think we can plan and build strategies for those transitions. We can ask questions like ‘what things do we need to avoid if we want the swimmers to stay in our club for a long time’?”

She then posts the sobering graphic with its cliff-edge decline from 12 years of age. Swimming’s loss. A big loss. Says Sandmark: “We lose a lot of swimmers and maybe that is good because maybe we don’t have space for them. Or maybe we could do a much better job to keep some of them.”

How? She summons up her own experience on the trail:

- watching lessons where she was “not always impressed”

- watching “very young leaders (teachers and coaches) who were not always interested in what they were doing

- watching training sessions where “swimmers, especially boys, are standing waiting for instruction and freezing and there is nothing else worse than freezing … And, of course, they stopped swimming, so I think we can do a much

Simon Sjodin – Photo Courtesy: Brendan Maloney-USA TODAY Sports

There are external factors, too, Sandmark notes. In Sweden, there’s a transition from grade 6 to 7 at school for those around 12 years of age. There’s puberty, too, from 12 to 14, on average, girls and boys, girls a little sooner. She says:

“That is the really big transition … we can see that’s a time of puberty, growth and also maybe the change from sixth grade to seventh, when they are given more work and a lot more responsibility. They’re asked to be more self-reliant.”

In Sweden, there’s another transition in school at around 15, or grade 9. “That’s when you have to choose if you want to be a swimmer. If you do, you have to choose the school for swimming [that allows and allows for swimming].”

Later, I will talk to Sandmark about the difference s among nations and note one of the biggest barriers to talent in Germany, where those who have not been identified as having a special talent and set on a pathway by 12 – the vast majority of children – have almost no chance of then making good in sport, finding the clubs and facilities and teachers and coaches capable of understanding who has talent and what to do about it at 14, 15, 16 and even later in some cases.

School starts at 7 and 7.30am in many parts of Germany. The dilemma is clear: unless the child attends ‘sports school’ – which would have meant being talent spotted or in a place where there is a local sports school (and moving to be a dormer if not), the child is not going “to do sport”, at least not in an elite sense. That, in turn, translates to a loss of potential talent in the pool of those available for elite training 0 and leaves the stone marked “no stone unturned” unturned.

The Mongrel Factor At The Start Of A Long Journey & Athlete Sustainability

If the system costs Germany a vast amount of talent lost to the Olympic feeder system, there is devil in the deeper detail: among those lost are some who may not have the most obvious physical or technical skills but have what Australian mentor Bill Sweetenham calls “The Mongrel Factor”.

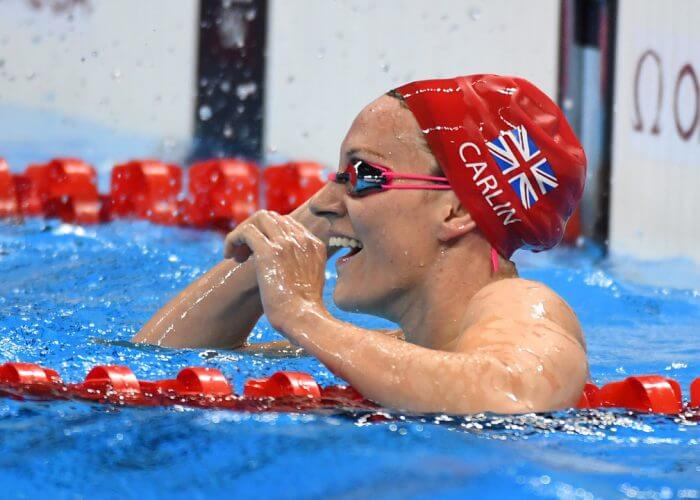

Jazz Carlin – Photo Courtesy: Christopher Hanewinckel-USA TODAY Sports

When Sweetenham set up the Smart Track squad in Britain that fostered the likes of Jazz Carlin, Fran Halsall, Lizzie Simmonds, Jemma Lowe, Ellen Gandy and Jess Dickons – each of them a podium placer for Britain and a home nation at global, continental and regional (Commonwealth) level, Carlin the later developer and lander of two Olympic silvers, over 400 and 800m freestyle behind American Katie Ledecky, the girls were 12, 13 and 14 years old. They had chaperones, knew ‘home-schooling’ on the road long before the current gen’ knew what that meant because of COVID-19, and Sweetenham told them and their parents and the media attending the selection event that “there are no guarantees – this is a very long journey”.

Don Talbot was a giant Aussie guru on the deck as an observer helping to spot the girls who would be selected for “Smart Track”. A third Australian, Chelsea Warr, who would go on to lead performance at UK Sport, was there too. It isn’t enough to show you could swim skilfully, beautifully. Sweetenham was on the lookout for the ‘mongrel’, meaning “attitude”. He got it in abundance with the likes of Halsall, Simmonds, Carlin and Co.

In Britain, each of the girls came via a local club, with good grounding of a local coach (some of whom are the most underrated and under-appreciated folk in sport). They would be moving on to more senior programs and new coaches down the line – and that required local understanding and support, too. In Germany, many of the Smart Trackers would have been lost to swimming had their parents not been in a place to get their kids to a sports school, assuming that the local sports school was even looking for the right things; assuming the parents were able to support a sports talent and sustain the commitment required; assuming the parents would not go so far and simply find it impossible to continue down the same pathway regardless of the potential in their child.

Sweetenham spoke of the role of parents and Warr worked with parents on educating them when it came to diet, sleep and all the other ‘daily habits’ required of athletes that are a part of a life less ordinary.

The Challenge Of COVID-19

Apply the above to local (national) circumstance and then to lockdown season 2020 and the oddest experience any have had in a swimming life in living memory and you hear the whisper on the wind: some may never make it back.

A whole raft of kids may be lost to the sport. Yes, there may be a Phelps or a Ledecky in the midst but some of those will make it through (it is who they and their parents and circumstances are); the bigger issue is the numbers who don’t, the numbers who pay the club and entry fees that pay for coaches that feed the federation budget that keep the sport financially afloat.

Hard times ahead for some, even if lockdown easing goes as smoothly as we can all hope.

Mental and physical wellbeing are two of the overriding issues raised when it comes to the impact of pandemic lockdown.

There are plenty of tremendous efforts to point to at club and elite level where coaches and national programs have kept their communities wonderfully engaged, a sense of belonging, a degree of orientation, a chance to learn and up-skill among the ‘opportunities’ seized during lockdown.

Even so, there have been (and will be) casualties. Those include safety, learn-to-swim programs locked down far and wide and even as lockdown eases, teaching swimming remains toward the back of the queue on the lobby lists of sectors making their way back to a “new normal”. There are good reasons for caution, care and responsible planning if swimming is to return in safe and sustainable style.

I read in one article that “children’s swim skills will be underdeveloped just as we hit peak summer weather and pools and beaches begin reopening”. True. Welcome to a First-World problem, one that is common experience in much of the world yet, COVID or no COVID.

The skills mentioned pertain not only to the learner, of course. Developers approaching or at that age drop-off age in Sweden, may not be be able to attend the summer schools, camps and leagues that they and their parents would rely on. Such systems are a critical part of the answer to a question like ‘why is country X so good at swimming…?’

Jack Conger – Photo Courtesy: Becca Wyant

The Washington Post noted last week:

“On a sunny summer morning in 2005, Jack Conger entered Tilden Woods Pool in Rockville unaware he would leave that evening with Olympic dreams. Conger, 10 years old at the time, broke the pool’s record in the 25-meter backstroke. He figured he could set lofty career goals because the previous record holder, Michael Raab, was pretty good himself, finishing third at the Olympic trials in the 200-meter butterfly in 2004. Conger’s growing confidence was justified; he became an Olympic gold medalist in 2016.

The D.C. area has produced numerous Olympic swimmers, and many of their breakthroughs occurred competing for local summer leagues between ages 4 and 18. But with the novel coronavirus pandemic canceling those leagues, which would have begun around Memorial Day, youth swimmers will miss a year of development that could have been key to their futures.

“[The summer] really is the bedrock,” said Bob York, a veteran Northern Virginia Swimming League coach. “Everything pushes to the summer. They’ve worked all winter, and then your summer is gone. You have all this anticipation and then boom.”

Competitive summer swimming in the D.C. area goes back to 1952, and there are now 12 leagues. Coaches credit the area’s abundance of clubs and pools for helping produce talented swimmers. Many of those pools are closed.”

Local swim leagues in the United States provided the competitive birthing pools for generations, as this list indicates: Melissa Belote, Katie Ledecky, Tom Dolan, Mike Barrowman, Brad Schumacher, Ed Moses, Matt McLean, Mark Henderson, all Olympic teamsters (and most medal title and winners). Olympic hopefuls who swam the same stream include Phoebe Bacon, Andrew Seliskar, Erin Gemmell and Torri Huske.

“The summer season is special because it’s really just swimming time,” Gemmell, who competes for Potomac Woods Swim Club in Rockville, told The Washington Post.

“During the fall and the winter and the spring, you have to focus on school and school swimming. In summer, it’s practice, nap, practice again, so you’re really just spending most of your time focusing on swimming and seeing your swimming friends.”

Conger puts it well when he says:

“Summer league swimming kind of opens that door for you. and it’s up to you whether you want to take it or not.”

Not this season. Coaches now fear that the sport’s participation will drop as a result. Some will miss a keys age of development, though just how that may or may not play out is part of the unknown of a post-COVID world.

What Does Athlete Sustainability And A Long Career Look Like?

Ulrika Sandmark asked the coaches gathered in Lund before the pandemic was declared: “What does a sustainable swim career look like for you? Are you asking yourself ‘do I have a good base that makes me prepared for all steps and progressions and transitions?’

Sandmark gave her audience some tips when it came to answering ‘and… what is unsustainable?”:

- too much pressure from home

- likes from parents on Instagram after every race or even practice

- parents who congratulate their children/swimmers on Facebook because they have done a personal best and celebration is made public (she asks “What do they do when their kids don’t do a personal best?)

Therese Alshammar – Photo Courtesy: Gian Mattia Dalberto/Lapresse

She advocated educating parents so that they understood that the child must own their swimming, that the child needs validation for who they are, not for their performance. The same principles applied to coaches, she noted.

Sandmark asked coaches to think about how to handle their own local situations. She asks the same questions of herself, pondering: “Should I just continue with the same system and then have a lot of swimmers disappear? In Sweden there are 22 ‘swimming gymnasiums’ (high schools with a swimming program). However, she notes “unfortunately, not all of them have a progressive program”.

In short, she meant: they don’t do enough work and the intensity of work is not what it should be along the years of development.

Then, the young athlete finds him or herself at 18 or 19 and having to choose. Says Sandmark:

“This is a horrible time, at least in Sweden. Should you continue swimming? Yeah, there are some clubs that have seniors, but I think I can count them on one hand.”

There are two other options: a national training centre – or college in the United States. She doesn’t dissuade people from going down that route. Most return to Sweden in the summer and, Sandmark notes, for whatever reason – school work, the distractions of life, programs geared for a college team moment but not a long International season – “they’re not as good as they were when they left and that’s not good”.

So, where to start making changes? She returns to the 12-year-olds. Enter Therese Alshammar.

Tomorrow, we will look at why Sandmark would turn to Alshammar for help in answering her own questions of Athlete Sustainability.

Canada I am sure would indicate a similar curve. 12 for boys and maybe 15 for girls from my impression as a past swim mom.

Yvette Putter Peterson true in the US also. I would even say those numbers would be on target here.

I think this is true of every sport. Many kids before the age of 13 are trying out multiple sports. Every sport becomes more time demanding, so by the age of 13 many are forced to pick just one.