As BBC Counts Down To “Where’s George Gibney” Podcast, Efforts Of Dr. Gary O’Toole To End Abuse Are Back In Focus

The story of Dr. Gary O’Toole, his courage, the courage he encouraged, the woeful failings of sports authorities and indeed the legal system to deliver justice to victims and survivors of sexual abuse in swimming is a tortured tale layered with issues that demand inquiry anew and changes to the law, including the scrapping of statute of limitations if and where it can be shown that law enforcement – or a lack of it – was a part of the problem, in their time and on their watch and now in our time and on our watch.

The mood for an overhaul of the system for tackling abuse is nowhere better highlighted than in the campaign led by Olympians and Athlete welfare advocates in the United States and their attempts to get U.S. Congress to force the change they accuse sports authorities of having resisted for long years.

The Year 2020 is one which lends itself to looking back in time at the round-number anniversaries of extraordinary and outstanding moments in swimming history. That lends itself to celebrating the fine achievements and pioneering of the likes of Helene Madison, Tracy Caulkins, Karen Moe, Duke Kahanamoku and Cecil Healy, Johnny Weissmuller, Lance Larson, Tom Malchow, Michael Phelps, Alex Popov and Tom Jager, Ian Thorpe in parts 1, 2 and 3, Inge de Bruijn and many more and much else.

There are other types of anniversaries, such as those that remind us of the dark side of the sport of swimming and the need to exorcise the ghosts of the past if we are to get the present and then the future right for generations of kids who need protecting from the rogues who prey on the young of any realm wherever they are given a chance, wherever the invitation on the door includes these words from The Watchman by Franz Kafka, from Parables and Paradoxes:

“I ran past the first watchman. Then I was horrified, ran back again and said to the watchman: ‘I ran through here while you were looking the other way.’ The watchman gazed ahead of him and said nothing. ‘I suppose I really oughtn’t to have done it,’ I said. The watchman still said nothing. ‘Does your silence indicate permission to pass?’.”

The Diagnosis Of Dr. Gary O’Toole For An Ill Left Untreated

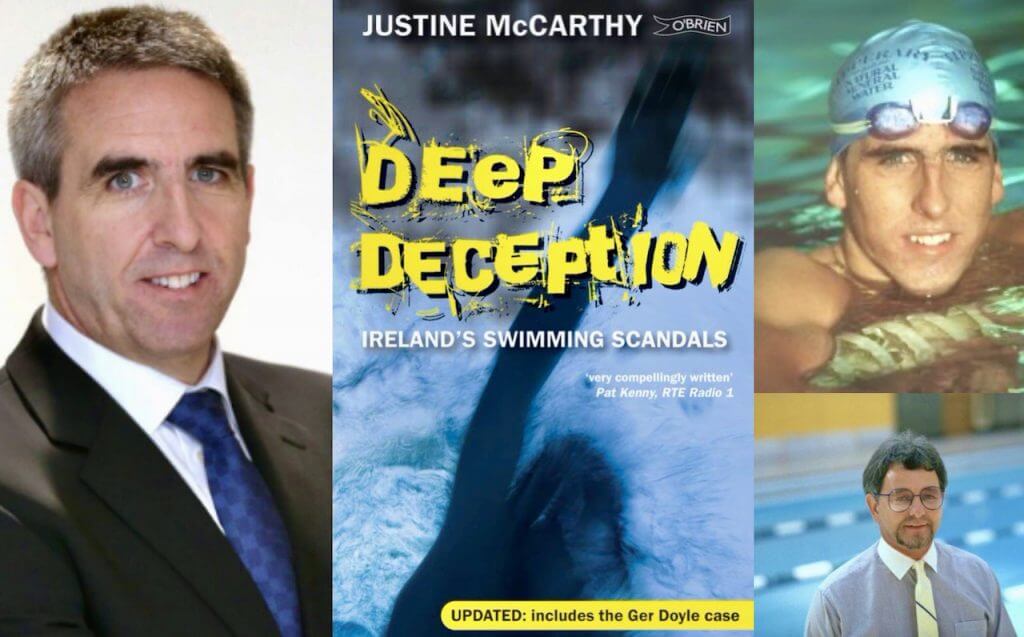

Dr. Gary O’Toole – Photo Courtesy: Beacon Hospital

In the same summer 40 years ago when Moscow was hosting the boycotted 1980 Olympic Games, the GDR’s State Plan 14:25 architects were plotting their next heist and swimming history was unfolding along a spectrum of opportunities lost and gained, fair or foul, the lot of athlete welfare well down the list of priorities far and wide, and 11-year-old called Gary O’Toole found himself on a training camp in California having to fend off the advances of his swimming coach, George Gibney.

The tale is well told in a fine reminder of woes unresolved from Johnny Watterson in The Irish Times today. Here’s how the reporter relates a chat, many years after, between O’Toole and another (then former) international swimmer, coach Francis “Chalkie” White: ” …Chalkie, privately approached O’Toole, who sat alone in a row of seats on the flight to Perth (1991 World Championships). Chalkie simply asked him “Do you get along with George?”

O’Toole replied: “Just professional. I wouldn’t have his phone number. I wouldn’t know where he lives.” It was then Chalkie began to talk about the years of breathtaking sexual abuse he had suffered.

As he spoke, O’Toole became aware that Chalkie’s terrifying history resonated in a profoundly personal way. It took him back to when he was an 11-year-old swimmer at a training camp in California in the summer of 1980.

Late one night Gibney had slipped quietly into O’Toole’s bedroom as he slept. As children do he pretended to be asleep. Gibney had a smell that the swimmers knew. In his car it was talcum powder. Other times it was body odour. O’Toole could smell him standing by his bedside. He kept still.

He then felt a hand on his leg and realised his coach was trying to get into the bed with him. Not all 11-year-olds would have had the strength of character. But O’Toole held strong and confronted his coach. In a pathetic pretence of normality Gibney produced an apple that he offered to O’Toole. The gift was rejected. Gibney left the room.

On the plane everything Chalkie was saying to him made perfect sense. The story stuck in his head and it didn’t help his swimming in Australia. O’Toole took 11th place in Perth. But the Olympic Games were the following year. With that in mind he took a break after the championships and arrived back to Ireland in February 1991.

His first act was to quit Gibney’s star-studded swimming team at Trojan. It was lose, lose for O’Toole. Lose if he stayed, lose if he left. Gibney wanted to know why.

“I think you know why,” replied O’Toole.

Within days of that Gibney had resigned as national coach, a position he had held for 11 years. It transpired that Chalkie White had also confronted Gibney and told him he would go public about the abuse if he did not resign.

The rest of that article, you can read at The Irish Times. The passage above is enough to haunt every parent who ever thought about letting their children move from learner to squad member at the start of a journey in the sport of swimming.

For deeper understanding of the sorrowful history related to Gary O’Toole’s valiant attempts to seek justice for Gibney’s victims and ensure that measures were put in place to make swimming a safe environment, Justine McCarthy’s “Deep Deception” is the place to start.

Where it should all have ended was in court, with Gibney facing due process, O’Toole, alongside others, has long opined. The story is now 40 years old, key people in positions of authority and power have been called out for wanting it to go away but Watterson’s article shows, it will not. He notes in The Irish Times today the timeline of torture for victims abused by those entrusted as teachers, let down by their guardians in sport and, ultimately, the legal system.

When Alarm Bells Rang In The Head Of Young Gary O’Toole

Gary O’Toole, of Ireland Photo Courtesy: Physician Athletes

It was January 2018 when Dr. Gary O’Toole told Newtalk’s Off The Ball sport show that he had been groomed by the man Irish media have long referred to as “the paedophile George Gibney” when he was a child.

Former national team coach to Ireland, Gibney was charged with 27 counts of indecent assault and ‘unlawful carnal knowledge’ of young swimmers in Ireland in 1993 but all charges were dropped in 1994 when it was decided that the accused could not properly defend himself as the complaints dated back to the 1970s.

Gibney has been living and working in the United States for the majority of the years since, having been granted a visa to stay and work there. His name is often cited in campaigns to rid American sport (and other realms where children can be found in educational settings) of sex predators among coaches and others working at the heart of organisations such as USA Gymnastics, the terrible tale of which is related in the documentary Athlete A, and in sports such as swimming, USA Swimming’s list of banned-for-life, published after decades of complaints from athletes, running into the many hundreds and the SafeSport system it now uses facing waves of criticism from safe sport advocates.

Dr. O’Toole referred back to the summer of 1980 in his talk with Newtalk’s Off The Ball in 2018. He said: “On that trip, I got terribly homesick, as one would when you are out there for five weeks. I remember breaking down and crying, and just saying ‘I want to go home.’

“He comforted me, as one would expect of an adult in that kind of a situation. Then I went to bed and I felt fine, but later on that night he snuck into my bedroom, he sat on the end of the bed and said ‘Are you feeling okay now?’

“I said, I feel fine. [He said] ‘I brought you up this apple,’ and he put this apple on the sideboard and then he said, ‘Are you sure you’re okay? Do you need any more comfort?.’

“I don’t know what it was, but immediately alarm bells went off and I said, ‘I’m fine. I think you should leave now,’ and he left.

“And that was the ‘in’, he got the opportunity. The vulnerability was there… I liked him praising me.”

Dr. Gary O’Toole, who represented Ireland at the Seoul and Barcelona Olympic Games in 1988 and 1992 and claimed silver over 200m breaststroke behind Britain’s Nick Gillingham in the 200m breaststroke at the 1989 European Championships in Bonn, said that he had not realised he was in danger until a teammate told him about his abuse in 1991. By then, O’Toole was 21.

It was at that point that O’Toole set out on the trail of tears and truth, seeking out others who might have suffered the same at the hands of Gibney. In 2018, Dr. Gary O’Toole said:

“I remember one night going to see this woman who I felt might have been one of his victims through the time. The front door opened, her husband was standing there and he looked me in the eyes and said, ‘Gary O’Toole – I’ve been expecting you for years. She’s in the kitchen. So, I went into the kitchen and spoke to her and he came in then eventually and he said, ‘You have no idea, I’ve been waiting for you because eventually, I was going to go down there with a shotgun and just stick it in his mouth.”

By the time O’Toole was done, a group of swimmers was willing to make a formal complaint about Gibney to the police. Their cases were not thrown out on the basis of whether they had truth to tell: it was just that time had passed and the law deemed that too much time had passed.

Deep Deception

Justine McCarthy’s Deep Deception – Photo Courtesy: The O’Brien Press

Down those years and since, much damage was done in Ireland and among Irish swimmers. McCarthy’s “Deep Deception”, which relates the story of Dr. Gary O’Toole, notes that in November 2009 former national and Olympic swimming coach Ger Doyle was convicted of thirty-five sexual offences against children.

It was just the latest of an appalling series of child sexual abuse scandals in Irish swimming. Before Doyle was charged, coaches Gibney, Derry O’Rourke and Frank McCann had become, as McCarthy notes “synonymous with some of the worst crimes against children ever to come before the Irish courts”. Then there was Father Ronald Bennett, founder of the Schools Swimming Association: he was also charged with sexual assaults against his pupils. Deep Deception states:

“All these coaches, the most respected in the sport, preyed on young swimmers. They exploited their dreams of greatness and betrayed the trust of their parents. Between them, they are believed to have left hundreds of victims in their wake. And the failure of the sport’s authorities to respond adequately to complaints paved the way for the abuse of many more young victims. In candid interviews, survivors outline the effects of the abuse – psychiatric illnesses, broken marriages, financial hardship, and alcohol and drug addiction.”

The book, now a decade old but as relevant now as it was at the time and would have been in the decades before publication, examines the structures of swimming, looks at the reasons these men escaped justice for so long and assesses the measures that have been taken to protect children in the aftermath of the scandals. What we learn in its pages resonates far and wide beyond Ireland.

In 2008, a 10-year battle for compensation by 13 female victims of Derry O’Rourke, the Irish coach convicted of sex abuse, has ended in a settlement for substantial damages against Swim Ireland and the private Dublin school that employed O’Rourke as a swim coach.

Swim Ireland was created in 1998 after the Irish Amateur Swimming Association (IASA) was dissolved.

King’s Hospital School, Palmerstown, Co Dublin and Swim Ireland had to pay 12 of the victims six-figure sums of compensation each under the terms of the settlement. Costs against King’s Hospital school were also awarded. The 13th victim’s settlement was a smaller sum in the agreement heard before Mr Justice Eamon De Valera.

They had been between 10 and 17 when the abuse occurred. O’Rourke, who once trained Michelle Smith, was sentenced to 12 years in prison in January 1998, after admitting 29 charges of sex abuse against schoolgirls. There were no allegations of impropriety in his dealings with Smith, who in the same month as O’Rourke was jailed provided a urine sample to anti-doping testers that would lead to her own fall from grace on the grounds of manipulating a test sample that turned out to have whiskey in it, according to anti-doping authorities. Smith’s case came into focus once more of late when China’s Sun Yang became the second swimmer after the Irish swimmer to have his anti-doping appeal hearing heard in public.

In 2008, Swim Ireland, which today has Safeguarding Policies and courses in place (with obligatory vetting of participants), welcomed the settlement, stating:

“All these victims suffered significant individual trauma and personal injury. We hope today’s outcome will help them to finally close the chapter on these painful events from their past lives. Dealing with the fact that child sexual abuse occurred in swimming has been difficult for everyone involved in swimming and Swim Ireland has worked very hard to ensure that all children who participate in aquatic sports can do so safely in the future. We would like to recognise the role of the many volunteers and parents who have maintained a steadfast commitment to the organisation and to the promotion of swimming in Ireland throughout this period.”

Appeal For Justice

Two years later, in 2010, newspaper adverts appeared in Ireland and the U.S. appealing to victims of George Gibney to help build a prosecution case against him.

One Child International, a non-profit, anti-child abuse organisation in Florida, campaigned to have Gibney either charged in America or extradited to Ireland for trial. The classified ads appeared in the Irish Evening Herald and a local newspaper in Denver, Colorado, where Gibney was coaching young swimmers. One Child still lists the search for Gibney among its open case files of AbuseWatch.

Ten years ago, One Child engaged Ken Smyth & Co, a Dublin solicitors’ firm, to serve victims.

“If charges aren’t raised shortly, Gibney’s going to walk,” Evin Daly, One Child’s director, told the Irish Sunday Times after a meeting in Dublin in 2010 with a senior official of the Department of Justice.

“I think the police and public interest in this will diminish quickly, so there’s an urgency about it. The Florida Department of Law Enforcement is aware of the investigation. We’ve met in person with Detective Ken Jones and police chief Frank Ross in that department. There are a couple of people that I’ve heard about who I hope will contact gardai (Irish police). If they feel more comfortable, our solicitor will accompany them.”

In reply to a letter from Daly enquiring about the possibility of having Gibney extradited, then Dermot Ahern, the minister for justice, wrote: “I am advised that the gardai will rigorously investigate any further complaints made by affected parties against him and take appropriate action.”

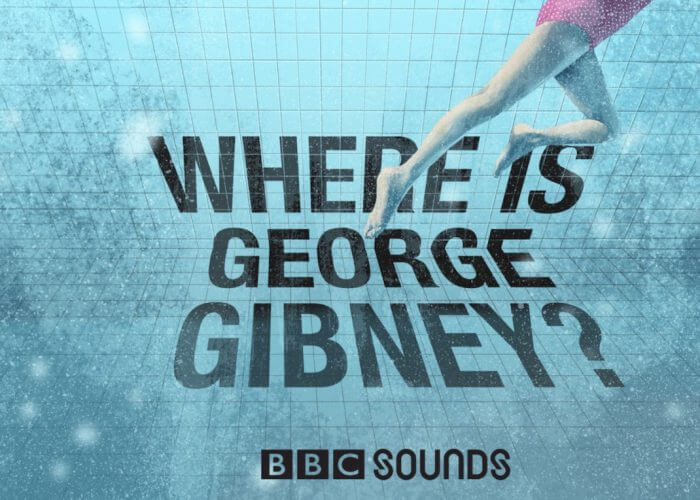

Where’s George Gibney – a BBC Sounds podcast coming soon … – Photo Courtesy: BBC Sounds

George Gibney was 63 at the time and was living in Orange City, Florida, where he held office in the Catholic church-run Knights of Columbus.

In July 2011, Gibney was dismissed from his job at the Wyndham Vacation Resorts hotel in Cypress Palms, Florida, after the Irish Daily Mail tracked him down and alerted One Child. A year later, sightings of Gibney were reported in Ireland and the gardai were cited as saying that, given no charges have been laid against him, he would have the normal protections of any citizen.

Down the years, Gibney held several jobs, including a couple of significant coaching positions. In the course of our own research, Swimming World has had sight of letters in which the American Swimming Coaches Association alerts potential employers to Gibney’s past, as well as other exchanges in which Gibney complains, through a lawyer, to ASCA that he is being prevented from gaining work by ASCA’s interventions.

Next month, August 2o20, the Second Captains investigative podcast series will air Where is George Gibney? When it airs on BC Sounds, the podcast will be “the culmination of 2 years work from the Second Captains team”. As many of those helping that team know, the story and the search for justice goes back much, much further.