An Agonizing Anniversary: 50 Years Since the Doping-Fueled Rise of East Germany

An Agonizing Anniversary: 50 Years Since the Doping-Fueled Rise of East Germany

From 1973 to 1989, the swimming world watched women swimmers from the German Democratic Republic rise from mediocrity (at best) to a fire-breathing presence that left the competition in ashes. Such was the power of the systematic-doping program launched by the communist nation.

********************************

It was the summer of 1973, and the sport was about to change. For the better? Yes. For the worse? Unfortunately, that was an affirmative, too. Sometimes, that’s how things work. For every positive, there can be a corresponding negative, and as FINA introduced a World Championships for the first time, the unveiling arrived at the dawn of a dark moment.

Through 1972, the premier athletes in swimming were largely limited when it came to shining on the world stage. They had the Olympics, of course, but that was a once-in-four-years spectacle, their efforts otherwise regionalized to meets such as the European Championships, Pan American Games, Commonwealth Games and national championships.

In an effort to provide its athletes with another global showcase, FINA designed the World Championships, with the first edition set in Belgrade, Yugoslavia. Going forward, the meet would serve as a midpoint—of sorts—between Games, and provide the best of the best with an additional chance to flash their skills and engage in elite battles with rivals.

However, as much as FINA (now World Aquatics) was moving in the right direction, it couldn’t derail a rising monster that was realizing the benefits of a systematic-doping program.

THE BEGINNINGS OF A DOPING-FUELED PROGRAM

The medals table from the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City reflects a three-medal haul by the East German women. More, five medals were collected by the East German women at the 1972 Games in Munich. These efforts depict a country that enjoyed select success in global competition, but nothing that suggests impending dominance.

However, at the inaugural World Champs, East Germany reigned with 18 medals in women’s competition. That total accounted for nearly half of the available podium positions, and the country won 10 of the 14 women’s titles.

What changed?

Well, this wasn’t a scenario in which an influx of talent changed fortunes. Rather, a doping-fueled program was at work, and Belgrade was just the beginning.

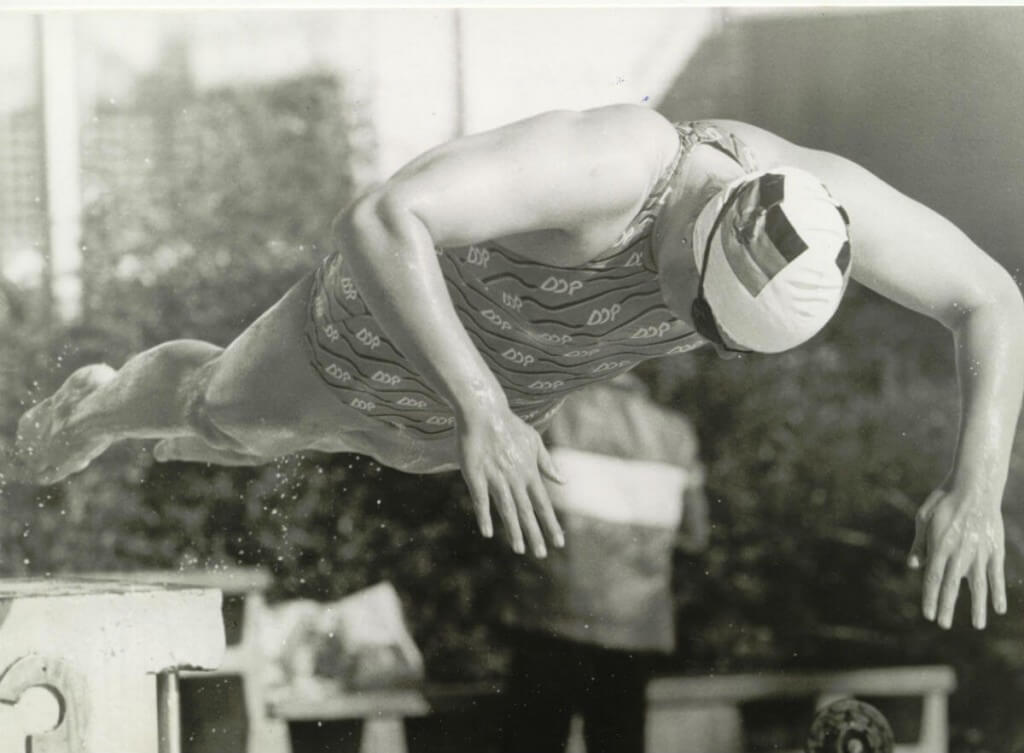

The female athletes wearing the colors of the German Democratic Republic (GDR) starkly contrasted their competitors. Their musculature was significantly more defined. Their voices were low. Acne breakouts were the norm. And their performances—including numerous world-record outings—reflected an improvement curve that was anything but typical.

When the East German dominance prevailed at the 1975 World Championships—and then the 1976 Olympic Games in Montreal—what was unfolding was clear. East Germany had implemented a government-run doping program that changed the landscape of swimming—and other sports. Yet, with this doping program ahead of the drug-testing protocols in place at the time, punishment was avoided. More, officials didn’t want to acknowledge the problem.

“Prior to the 1976 Olympics, the East Germans had just blown us away in the World Championships,” said Jack Nelson, the coach of the United States women at the Olympic Games in Montreal. “And our girls were honestly bothered by the fact that they had been the greatest team in the world for a while and then suddenly the East Germans just are blowing us away. We knew while we were there that they were beating up on us with steroids and whatever, and there was nothing we could do about it, right? Plus, we didn’t want to be the nasty Americans at the Olympics.”

1976: A TIPPING POINT

Photo Courtesy: Swimming World Magazine

If the 1973 World Championships served as the door-opening moment in East Germany’s rise, the 1976 Olympics represented the tipping point for foes of the Wundermädchen. As East Germany buried the opposition and rewrote the record book, frustration grew. Dutchwoman Enith Brigitha, a black woman in a predominantly white sport, was robbed of Olympic and world titles. The same could be said for several Americans, including Shirley Babashoff.

It was Babashoff who broke the silence regarding the East German regime. While coaches and athletes discussed the situation in private, it was Babashoff who went public with accusations of doping. But instead of igniting an investigation into East Germany’s overwhelming rise, Babashoff was admonished for her comments.

“They had gotten so big, and when we heard their voices, we thought we were in a coed locker room,” Babashoff said. “I don’t know why it wasn’t obvious to other people, too. I guess I was the scapegoat. Someone had to blame somebody. Something bad had to happen, and it had to happen to me. I didn’t get the gold. I got the silver, so I was (considered) ‘a loser.’”

INCREDIBLE DOMINANCE

While 1973 launched the start of East Germany’s illicit doping program, it was not a short-lived operation. The use of performance-enhancing substances remained in effect through 1989, when the Berlin Wall crumbled. Afterward, documents from the Stasi, the East German secret police, revealed the details of the process. Meanwhile, statistics emphasize the incredible dominance of the era:

- After holding zero world records at the conclusion of the 1972 season, East German women went on to set 127 world records between 1973 and 1989, including 110 individual global standards.

- During the three Olympiads in which East Germany competed during its doping era, it claimed 31 of a possible 40 gold medals, and won more than half of the total medals available, 64 of 120.

- There were five World Championships contested between 1973 and 1989, and East Germany won 44 of the 72 gold medals available, accounting for 61% of the titles.

- At the seven editions of the European Championships conducted from 1973 to 1989, East Germany won 96 of a possible 104 titles, good for a success rate of 92.3%.

NUMEROUS VICTIMS

The victims of East Germany’s government plan are wide-ranging. Clearly, the athletes who were beaten by illegal means rank at the top of the list, Babashoff arguably the most notable. But the East German athletes—teens who were fed drugs—were also victimized. Not only have numerous athletes endured medical side effects, but they have also been left with doubts concerning their ability.

For every Kornelia Ender or Kristin Otto, who have stopped short of admitting their knowledge of the East German program, there is a Rica Reinisch. A three-time Olympic champion at the 1980 Games in Moscow, Reinisch harbors anger, disappointment and uncertainty.

“We were guinea pigs, there to win Olympic gold, used like a taster in ancient Rome,” Reinisch once said. “The worst thing is they took away from me the opportunity to ever know if I could have won the gold medals without the steroids. That’s the greatest betrayal of all.”

A betrayal for sure, and one that began 50 years ago, changing the history of the sport.