2020s Vision – The Athlete Voice: Matt Biondi’s Mission To Enrich & Educate Swimmers

Over the coming year, Swimming World will consider key challenges facing aquatic sports athletes, swimming, swimmers, players, coaches, leaders and others working in this, one of the biggest, Olympic sports and its governance in the decade ahead. In the first quarter, 2020sVision will ask for the considered opinions and views of experts and players from various angles on three themes, namely The Athlete Voice; Swimming Culture; and Gender Vs Sex – a waking nightmare for women’s sport?

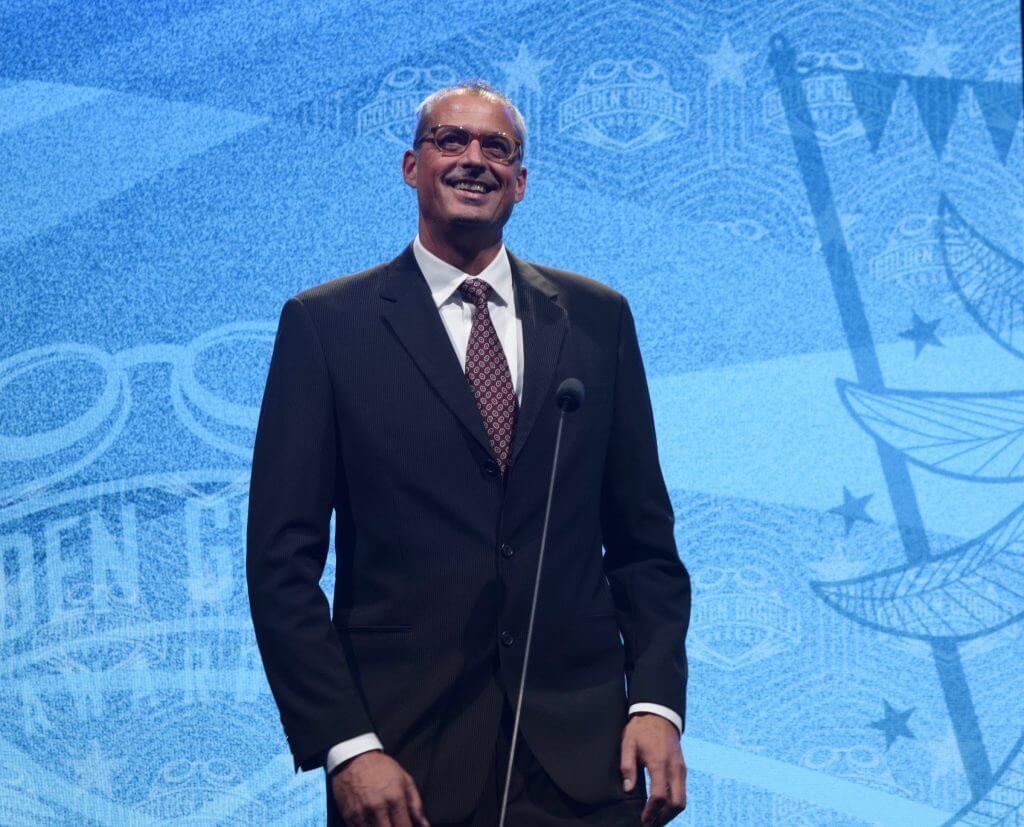

Today, we turn to Matt Biondi, a swim legend returned to a key role in the sport as director of the International Swimmers’ Alliance. He sees his job as educating athletes as well as taking their voices to the top tables of governance.

Biondi will be asking the International Olympic Committee (IOC) what it thinks about sharing $100m of the $700m it takes for itself from Games revenue generated by the show the athletes deliver; that would mean $2m in prizes per pool race, including $600,000 per gold.

In return, swimmers will have to step up and understand more about their workplace, which includes the kind of politics the Olympic Movement is steeped in, the kind that has dictated whether some even got to race at the Games, the kind like the Moscow 1980 boycott that haunts people throughout their lives, the kind of politics they, as athletes, are not allowed to bring to the blocks and podium in the pool.

Biondi wants then to step up not just in brawn but brain, too. He says:

“I’ve had more success at the top level with the European swimmers than I have with the American swimmers and I think it’s just a part of the culture of the sport: athletes, so many of them, I would say, conservatively, three out of five, have no opinion at all. They just don’t know what to make of it.

“It breaks the mould of what they think of swimming: wake up early, I go to the pool…, I do what my coach tells me to, I go home, I eat, I study, I sleep, I go back to the pool. And that’s the extent of their ability to understand all the many components that go into the Olympics.

Part 1: Money, Medals & Why Athletes Need To Understand Their Workplace

Energy Standard captain Chad Le Clos lifts the trophy – Photo Courtesy: Gian Mattia D’Alberto/LaPresse

The Athlete Voice. What is it? What will it ask for? What can it achieve? We’ll be looking at those questions in subsequent articles in this 2020s Vision series.

Among those seeking answers is Matt Biondi, one of the legends of the sport of swimming, winner of five golds and seven medals in all at the 1988 Olympic Games and now a founder, Director and first employee of the International Swimmers’ Alliance.

It was November 22 in London last year when Swimming World broke the news that Biondi had stepped back into the sport at the dawn of a new Pro-Swim era brought on by the International Swimming League and its founder and funder Konstantin Grigorishin. Biondi was leaving teaching after 17 years. The timing was part of a perfect storm: Biondi’s son Nate and Grigorishin’s son Ivan had become friends at Cal Berkeley. Contact was made and a calling was reborn. Biondi would now be Director of the Swimmers’ Alliance.

He sits at the helm of a board of 10, six of whom are swimmers. They are among 50 signed-up athlete members from 20 of the leading swimming nations of the world. The number is less significant than who the swimmers are: the count includes a shoal of Olympic and World champions, other big podium placers and world-record holders.

What do they want? Fair Play, Fair Pay in return for their Citius, Altius, Fortius and the show that simply would not be without such excellence in a trillion-dollar-a-year industry from which athletes in Olympic sports have been thrown relative crumbs.

They also want their voices heard at the top tables of governance, including the IOC and FINA, the international federation, says Biondi. Leading athletes spoke out last year on why they want their voices heard unfiltered by in-house athlete committees they see as too often staying on-official-message, a theme we’ll be returning to later in the series.

Katinka Hosszu – Photo Courtesy: Patrick B. Kraemer

Leadership figures among those in-house committees admit privately to journalists and athletes that they feel they have to represent the official body first and foremost. They don’t feel that they would have lasted long had they raised the issues and demanded the kind of changes we have heard being made by the likes of Katinka Hosszu, Cate Campbell and Adam Peaty, not to mention the demands at the heart of ISL-led legal action in which Tom Shields and Michael Andrew have played a lead role alongside Hosszu.

Biondi is working with athletes to have their voices and views heard and acted upon by the governors of their sport. There may well be hard talks and knocks ahead and not all of that will be about money.

The antagonism that has played out over doping, with podium protests at the World Championships making headlines around the world, and other contentious issues being raised by athletes has led to talk of boycott, union representation and division.

Matt Biondi wanted to be clear as we took up where our London interview had left off last November:

“It’s not about boycott. It’s not a union.”

He explains the perception he wants to sink: “Lot of times they [the athletes] think we’re going to ask them to stay out of the Olympics. That’s not the case. But with this collective voice, we think that it’s fair to pay prize money at the Olympics.”

Down to business. The Alliance will have many issues to raise but here’s the one taking up most oxygen at the outset of a big shift in swimming: Fair Play For Pay.

In the past year, FINA, under legal challenge, under the guidance of the IOC and for pragmatic reasons, relaxed its hold on the monopoly of swimming it has held since its formation in 1908. It did so by allowing the Swim League, an entity that is not affiliated to FINA, to organise world-class competition involving members of federations operating under rules that have prevented such engagement.

Rio in Olympic mode – Photo Courtesy: Swimming World

Biondi is about to take the next step. Here is the message he wants the IOC, FINA and others to hear directly from the athletes:

“It’s [Olympic sport] a 7.5-billion-dollar industry. The IOC makes 10% right off the top, that’s $700 million. Even if the swimmers could negotiate 100 million that’s 2 million per event and 600,000 for a gold. That’s the level of financial contribution that swimmers are making to the Olympics.

“But the paradigm is that they get zero. It’s a perfect business model. What company expects their top employees to perform for free?”

Given that the people and organisations Biondi will have to deal with are the same as those accused by coaches of having ignored and shunned calls for change for many years, what would he do if overtures to the IOC and FINA fall on deaf ears? What, for example, would happen if his request to talk business is met with similar silence and lack of response as that experienced by the likes of Bill Sweetenham, the World Swimming Coaches Association, its American counterpart and others when they asked FINA’s leadership for talks over a proposal to engage in a standard review process? Says Biondi:

“Ultimately, it’s to their survival: Olympic sports leaders will either move with the times or become obsolete, which for 90% of the swimmers is like an idea that says we’re gonna reach up and touch the moon. The Olympics in swimming is the Almighty. My job is to educate them.”

The Swim Culture Biondi Found On His Return To The Deep End

Biondi started his new role quietly on July 1, 2019. “I took two California trips to assess what the mood was among the swimmers. I wanted to know what their thoughts would be about joining together in this Swimmer’s Alliance and partnership.”

First up, he went to what he calls “my safe ground”: his alma mater, Cal Berkeley, where coach Dave Durden and some of his charges listened to Biondi’s first presentation.

Then came a visit to Stanford “and a man with only one swimmer there, apparently …”. Biondi breaks into brief laughter. Simone (Manuel) and Katie (Ledecky) … I couldn’t get a hold of. I think they knew I was there, maybe not, or maybe they just didn’t want to come.” There’s a little laughter again but his tone remains serious.

He’s a man and former athlete who tried to force change long ago and understood then, as he does now, that the pathway he embarked on and now returns to did and still does include barriers and hurdles, some put up by the athletes themselves, wittingly or otherwise.

“The reaction of the swimmers has been very interesting to see,” says Biondi.

“I think I’ve heard elements of the whole spectrum, from those who just want to compete with the ideals of amateurism to those who don’t want to touch it because they have a big name for themselves and they don’t want to risk any kind of ‘negative’ publicity with their sponsors going into the Olympics.”

He’s spoken about his own experience and gets the current mindset: “I can certainly relate to that…”

Pablo Morales – Photo Courtesy: Bob Martin/Allsport

How does he explain it; is it partly down to them having grown up in a culture that has not encouraged swimmers to ask for a fair share? Has the culture made swimmers and parents feel grateful for what they do get and always asked them to be tough and not complain? And, in parts of the world where selection is not simply a matter of being the best and there’s a reliance on the thumbs up or thumbs down of selectors, does prevailing culture encourage silence?”

“Sure,” he replies. “And that works both ways, too: my good friend and rival Pablo Morales was world record holder in butterfly – and he got three thirds in ’88 trials. You don’t complain … it’s how it is.”

Sometimes, ‘how it is’ exposes athletes to media scrutiny and criticism over their switch from active sportspeople to governance roles. This piece at Medal Count under the headline There is no Defense for the Actions of Mary Lou Retton is a case in point.

‘Europeans Understand; Americans Don’t Know What To Make Of It’

With a nod to the wider world of athletes he now represents, Biondi credits Europeans with a deeper understanding of the realm they work in:

“One of the really interesting parts of my job is that I’m talking to swimmers all over the world. I can see that the collective knowledge of the European swimmers has much more of a broad scope in that they understand their sport, their training, like all athletes do, but they also understand the organisation in which they’re competing, they have a better business sense of the revenue issues, of their sports value and their commercial value.”

“The language barrier is an issue … but I’ve had more success at the top level with the European swimmers than I have with the American swimmers and I think it’s just a part of the culture of the sport: athletes, so many of them, I would say, conservatively, three out of five, have no opinion at all. They just don’t know what to make of it.

“It breaks the mould of what they think of swimming: wake up early, I go to the pool…, I do what my coach tells me to, I go home, I eat, I study, I sleep, I go back to the pool. And that’s the extent of their ability to understand all the many components that go into the Olympics.

“For example: the revenue, what is generated and what the Olympics have become. If you want to compare the true amateurism of 50 years ago and look at the revenue of it 50 years ago, it’s peanuts compared to what it is today. It’s really grown and modernised.”

Sport Has become Big Business – But Not For The Swimmer

Biondi notes that pressure for the Olympics to rethink its model is “part of a bigger movement” for change and modernisation:

“We see it in the NCAA with our Fair Pay for Play Act signed by California Governor Gavin Newsom. Initially it was an innovation and disruption to the NCAA system, which has always ruled with an iron fist,” says Biondi. “And then two weeks later they opened negotiations with their Athletic departments to come up with a set of rules to incorporate agents and commercialism in NCAA, which is landmark stuff, unheard of.”

He notes the trouble in Track and Field over Diamond League program cuts and concludes:

“So, the time is right, the time is good for swimmers to start to understand all the components of the sport they work in, and hopefully, by speaking with one large voice, we can affect some really meaningful change.”

Tomorrow, Part 2 of Matt Biondi and the Swimmers’ Alliance

In this first quarter of the new decade and 2020, we will consider the following themes:

- The Athlete Voice

- Swimming Culture – what is it?

- Gender Vs Sex: a waking nightmare for women’s sport?

Do you have a contribution to make, a topic to suggest within the frame of the themes we are looking at this quarter? Your views on any theme can be left in the comments field at the foot of any article, while those who want to reach out with suggestions to the editorial team can contact us at editorial@swimmingworld.com.

Brawn and brain

Break the mold

You need to proofread your articles.

Thanks Christie… brawn is good (oops); your mold is not 🙂 … mold is the stuff the grows on wet windows and in damp corners… break the mould means mould as in the form in which things take shape… the spelling of mold in that context is only used in America because you dropped the u’s in everything … we’re a global website and its hard to always be consistent… but in English, its mould for form, mold for dank 🙂

Ah, American vs English. There are a ton of typos. I’ve screen shot a number, but I’m not sure how to attach them. Question: is the plural “their” now used when the subject is singular?

You can send them to editorial@Ken.com, Christie. I suspect your ‘ton’ is somewhat overdone ?. The use of their for a singular team or nation or company, etc., has entered the ‘style’ books of many media outlets, including big mainstream titles. Again, the use is not always consistent (in part because of the workload involved, especially in the absence of an army of sub-editors and the presence of time constraints).

Done!

??