The Misconceptions of Breaststroke Breathing

Swimming Technique Misconceptions: Breaststroke Breathing

PHOENIX-Many people believe that the technique of the fastest swimmers is worth copying, resulting in numerous misconceptions. In reality, even the fastest swimmers have technique limitations, but they offset them with strength and conditioning. The purpose of this series of articles is to address scientifically the technique misconceptions that have become “conventional wisdom,” and to present more effective options.

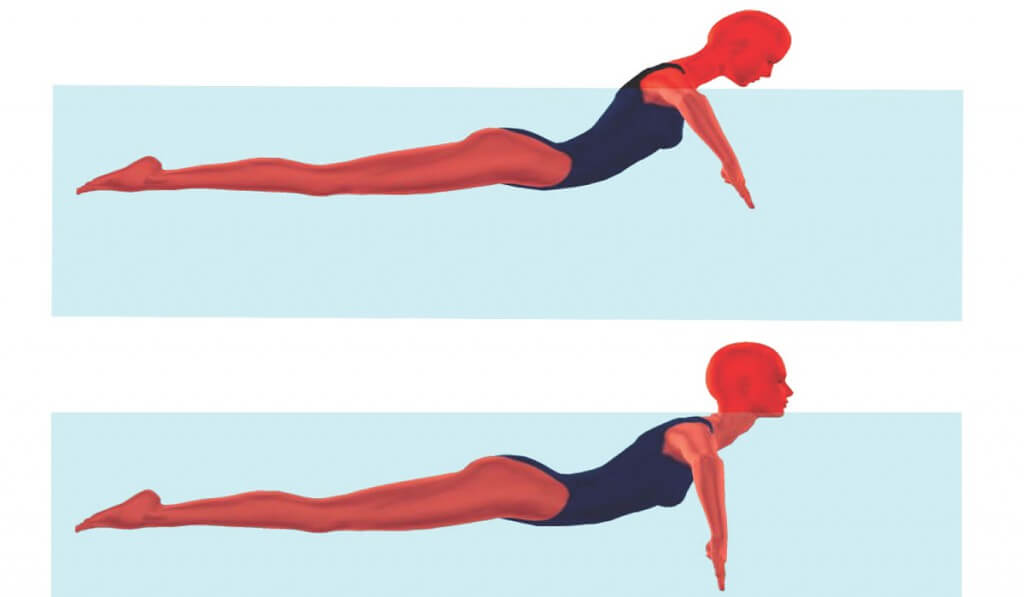

A common technique misconception is that a breastroker should not change the angle at the neck to breathe. Typical advice is to maintain the non-breathing neck angle when breathing to avoid straining the neck and causing resistance by dropping the hips. However, swimmers can actually minimize resistance without neck injury by using the full range of motion of the neck to breath.

The conventional wisdom is to maintain the same angle at the neck during breathing and non-breathing in breastroke. However, if the swimmer does not change the neck angle, then he/she must change the body angle to position the mouth above the surface. When the body angle changes, the swimmer generates excess resistance, expends more-energy and swims slower.

An effective breathing motion requires extension at the neck through the full range of motion. If a swimmer completely extends at the neck, the body remains more horizontal so that resistance is minimal, the arm motion is more effective, the body travels a shorter path, and the swimmer can more quickly regain the streamline position on every stroke cycle. A swimmer can expedite the learning process by focusing on cues to change the breathing motion.

More of this article on pages 20 and 21 of the June 2015 Issue of Swimming World Magazine. The article was written by Dr. Rod Havriluk who is a sports scientist and consultant who specializes in swimming technique instruction and analysis. His unique strategies provide rapid improvement while avoiding injury. Learn more at the STR website—swimmingtechnology.com.

Get you copy of the June 2015 Issue of Swimming World Magazine now!

Check out the inside Swimming World video:

Not a subscriber? Swimming World Magazine Subscription gives you unlimited access to all online content on SwimmingWorldMagazine.com and access to all of the back issues of Swimming World Magazine dating back to 1960! Purchase your Total Access Subscription TODAY!

JUNE TABLE OF CONTENTS:

FEATURES

014 Rockstar Seliskar

by Annie Grevers

Andrew Seliskar of Nation’s Capital Swim Club is headed to Cal this fall as the No. 1 college recruit in the country. His club coach, John Flanagan, is quick to add, “That talent is coupled with really great character traits”.

025 Getting To Know Nicole Johnson, The Future Mrs. Phelps

by Annie Grevers

Swimming World Magazine had the opportunity to sit down with Michael Phelps’ gracious fiancée during the Arena Pro Swim Series in Mesa, Ariz.

026 Summer Swimming’s Stepping Stones?

by Jeff Commings

Two international meets are being held this July that could possibly foretell future success at next year’s Olympic Games in Rio.

028 Comeback Queens

by Annie Grevers

Olympic medalists and world champions Katie Hoff and Jessica Hardy share their stories of returning to swimming after injury.

030 Pooling Team Excellence

by Annie Grevers

Swimming World Magazine reached out to some seasoned talents to find out what makes the water in certain team environments more inviting and more productive.

COACHING

010 Lessons With the Legends: Jon Urbanchek

by Michael J. Stott

018 Basics of Butterfly Training: 100 vs. 200 FLY

by Michael J. Stott

Training for the 100 and 200 fly today is a lot different than the way swimmers used to train for the two events in years past.

022 Swimming Technique Misconceptions: Breaststroke Breathing

by Rod Havriluk

A common swimming technique misconception is that a breastroker should not change the angle at the neck to breathe. Typical advice is to maintain the non-breathing neck angle when breathing to avoid straining the neck and causing resistance by dropping the hips. However, swimmers can actually minimize resistance without neck injury by using the full range of motion of the neck to breathe.

033 2015 Aquatic Directory (Click Here To View)

052 Q & A With Coach Chris Plumb

by Michael J. Stott

053 How They Train Amy Bilquist, Claire Adams and Veronica Burchill

by Michael J. Stott

TRAINING

013 Dryside Training: On-land Swim Stroke Movements-Breastroke

by J.R. Rosania

JUNIOR SWIMMER

046 Up & Comers

COLUMNS

008 A Voice For The Sport

033 2015 Aquatic Directory

047 Gutter Talk

048 Parting Shot

Gert Norg Marleen Welten

Yasso Tawfik (Y)

Яна Хасьянова

Zane Rademaker

Shaun Abbott

Great analysis!

Calo Gv

Margarida Neves

Brian Culver!!!

Maddy Nasrallah

The images are not showing shrugged shoulders, which allows higher arm recovery while keeping the body low.

The images are simply ludicrous and have no place in a serious article.

Byron,

Thanks for your comment. “Shoulder shrug” is another misconception because it wastes energy with vertical motion, generates excess resistance, and compromises propulsion on the inward sculling motion.

Rod

Brianna Back

Hmmmm……. don’t know about ‘great analysis’; I think it is over-simplified. When the hands and forearms scull/press inwards the head and shoulders lift as a natural consequence. Swimmers with strong upper bodies will rise to a greater extent than those who are weak. You may as well breathe at that point in the stroke because nature is on your side. When the swimmer hits this point the knees have bent and the feet are being positioned for the most advantageous angle to produce propulsive force. That is the over-riding consideration. That ‘best position’ depends on the size and shape of the feet together with the flexibility of the ankles. The feet have to stay underwater so the angle of the body and thighs is constrained by the length of the lower legs which have, in turn, to be positioned vertically so that force production is not compromised.

All those things contribute to the degree if shoulder rise and the optimum body angle. The degree of neck flexion is a secondary level of consideration surely?

Clive,

Thanks for your comments. You bring up a couple of important points.

Upward motion certainly is natural, unfortunately it’s also ineffective. If a swimmer avoids the natural tendency to go up to breathe, he/she can stay more level and generate more arm propulsion.

It is definitely a challenge for a swimmer to keep the feet submerged on the kick recovery when the body is more level. Check how MONA (the STR biomechanical model) recovers the legs to achieve an effective position for maximum leg propulsion.

https://swimmingtechnology.com/products/mona/breaststroke/

Rod

Dear Dr. Havriluk, It could be that we are trying to say the same things as each other but I am having difficulty understanding the rationale of your analysis and prescriptions. Maybe we are scurrying along on parallel watery planets

The insweep of the hands and forearms causes the rise of the chest and shoulders, and also the head because, as the song graphically tells us, “the neck bone is connected to the shoulder bone”. “[S]tay[ing] more level and generat[ing] more arm propulsion” has, therefore, already happened when the shoulders rise. I don’t think anyone is arguing that the swimmers should not stay as streamlined as possible during the hand outsweep so that part is axiomatic. The swimmer also has to breathe at sometime so my view is they may as well do it when the natural rise of the shoulders encourages it. If, as you suggest, the swimmer deliberately avoids the natural tendency to go up to breathe then they are fighting nature – not a good idea at the best of times. The biggest fault I see is the popular (and ugly) tendency to ‘smash’ the face down into the water while the shoulders are still at a high-ish position.

The MONA model looks as if it is concentrating solely (pun not intended) on the foot and lower leg movement. However, as we all know, the breaststroke leg kick gains its power from muscles in the butt and thighs as well as the lower legs. In order to bring those (big; big, huge) muscles into effective play surely the angle of the torso/thighs and thighs/lower legs have to change somewhat from what you are suggesting?

The graphics included with the Swimming World article and the MONA model are, indeed (as Kindly Contributor Gordon Belbin says), reminiscent of 1960’s style breaststroke where the inhalation was taken during the outsweep of the hands (“early” breathing). The reason no successful breaststrokers do this anymore is that it is inefficient. It results in a stop/start breaststroke rhythm where the front half of the body operates seemingly independently of the back half; a bit like a pantomime horse built from two complete strangers.

As the shoulders rise the hips will naturally fall. If the knees relax at this time the feet will naturally rise towards the buttocks and make it easier for the swimmer to place in an effective catch/fix position; nature again.

The ideal kick will fix the feet as much as possible and then move the hips forwards and away from the feet using the levers and linkages of the lower leg, thigh and hips. Kicking the feet backwards and moving the hips forwards are related but different considerations surely?

Movements in swimming cannot be viewed in isolation; the stroke cycle is a dynamic. Change one part and you affect all the other parts. It is misleading to consider the breathing pattern/style/technique/timing without simultaneously considering the arm action and the resulting body position which, in turn, affects the effectiveness of the subsequent kick. The whole cycle has to be under consideration.

Clive,

I really appreciate your willingness to continue to dialog. You brought up some additional important points regarding natural movements, the kicking motion, the timing for breathing, and how the movements of body segments fit together.

Most natural movements that humans make in the water are at least ineffective and usually counterproductive. The upward motion to breathe in breaststroke is a classic example. As the head begins to move up, the hands and lower arms naturally move into a more horizontal position to generate upward force. While this motion is natural, it reduces propulsive force.

MONA’s kick recovery minimizes resistance, as shown in the images on the STR website. When she completes the recovery, her legs are in position to generate maximum propulsion. If her torso was elevated, she would generate less force in the horizontal direction.

Regarding timing for breathing, MONA does not move her head from the streamline position until after she begins the pull. The full version of MONA (with the images for the entire stroke cycle) show a very smooth change in the angle at the neck to breathe and a very smooth transition back into the streamline as the head follows the arms forward.

Your point about how the “whole cycle has to be under consideration” succinctly summarizes why there are so many technique misconceptions. A noticeable technique element of a champion is often adopted with no scientific basis and no consideration of how that technique element impacts the rest of the stroke cycle. In contrast, all of MONA’s technique elements were developed from science (physics, research, and thousands of Aquanex trials).

Rod

These pictures are misleading. They’re suggesting that it’s better to keep your shoulders under the surface when you breathe! What year is this? 1965?

Gordon,

Thanks for your comment. When the shoulders are submerged, the arms are in a more effective position to generate propulsion. There are effective technique elements from 1965, just are there are ineffective technique elements from 2015.

Rod

I don’t think anyone is suggesting that the shoulders should be above water when the arm propulsion is generated. It seems to me that the concern is the suggestion that the shoulders should stay under whe the natural forces of nature are making them rise as a RESULT of the propulsion. At that time it seems sensible to breathe. Why not?

Dr. Havriluk, When I saw the title of this article, I have to say I was intrigued. I read the entire article online today and can see how this works, never thought I would agree. I had not thought of teaching breaststroke that way-always recommended that the neck stay inline with the upper back, eyes focused down on the water. It’s to bad the entire article isn’t posted, but I guess that’s the point. Thanks for the article.

Keffer,

Thanks for the feedback. It’s easier and more natural for a swimmer not to extend at the neck. Consequently, many swimmers resist the change. However, the ones who do change benefit by saving energy and swimming faster.

Rod