Favourite Pools: Algés e Dafundo Where The Water & Walls Sing A Universal Song Of Swimming

Favourite Pools. Today, Craig Lord on Algés E Dafundo, a childhood haunt whose people and events resonate yet almost a half a century on. The song of swimming is a composition of many languages but strung together with connections and common threads we can all understand should we have an ear to do so. Here are a few notes in the swimming symphony told through a pool that was and is home to a swimming family whose stories, smiles, sorrows and saudades live not only in memory but remind us how the past is still playing out at a time of discrimination and demands for change.

What are your favourite pools? As the swimming-less summer of 2020 draws on, the team at Swimming World is taking a look at some of the great pools we love the most, why and what makes them so special. We’ve asked you to join in the fun and memories with your own suggestions, either by leaving a comment or sending us a picture you took of the venue you’ve chosen along with some words on why the place is one of your favourites: editorial@swimmingworld.com (some readers’ choices due next week).

Our series so far:

- Craig Lord: Stadio Olimpico del Nuoto at the Foro Italico

- Ian Hanson: North Sydney Olympic Pool

- Andy Ross: William Woollett Aquatic Center

- John Lohn: Indiana University Natatorium

- Liz Byrnes: Favourite Pools: Swimming In The Snow At Hathersage Open Air Pool

Sunday Essay: Language Lessons In A Swimming Life

Deep below the main pool at Algés e Dafundo on the outskirts of Lisbon in Portugal, there was a teaching tank, dimly lit, water warm, the steady drone of the subterranean plant at the heart of the venue soporific to some, merely the hum of a crowd to me. There did I swim my greatest races, cheered on to soaring triumphs over Mark Spitz, Brad Cooper, Mike Burton, Gunnar Larsson and others who could only dream of being so fast at 10.

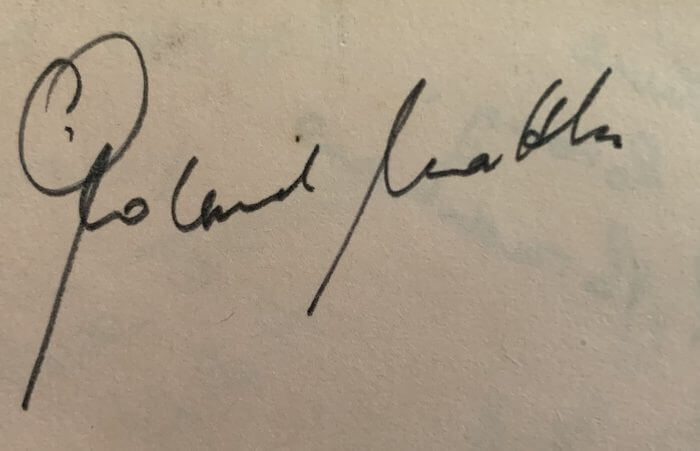

The pen roll of the Rolls-Royce of backstroke – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

I even matched Roland Matthes once. I could never quite bring myself to actually beat him: among differences between me and John Naber, what we have in common respect, admiration and appreciation of the stature and the kindness in a man and athlete who lit a spark in this inner swimmer the first time we met. I was 8 and at the top of my birthday wishlist was a Porylastic suit, yellow, just like Matthes had worn in warm-up at Crystal Palace in London before spinning me in the air and signing my autograph book.

Santa had a great year. And so did I.

Around the same time, I was told we would be leaving England and going to live in a place called Portugal. By then, though I didn’t realise it at the time, what had been true for Roald Dahl’s Matilda, minus the telekinesis, was working for me. Dahl wrote:

“The books transported her into new worlds and introduced her to amazing people who lived exciting lives. She went on olden-day sailing ships with Joseph Conrad. She went to Africa with Ernest Hemingway and to India with Rudyard Kipling. She travelled all over the world while sitting in her little room in an English village.”

By the time I arrived with my family to live in Lisbon, I’d sailed the Seven Seas through the swimming books and magazines, Swimming World among them, that lined the walls and floors and desk of my father’s office, garage and other places apparently less acceptable to my mother.

Craig Lord’s first swim medals – Photo Courtesy: the recipient

I’d won my first medals in swimming at 6 in the Medway (Kent, England) under 8s championship, a gold in the 100yds backstroke among them. With all that travelling on a sea of swimming worlds, by the time I had to line up at meets in a place where they spoke another tongue, the language of swimming was what counted most those first six months on the way to a childhood fluency in Portuguese: I knew where to get the entry card I had to take to my blocks with me, knew where to wait, to keep an eye on the board and clock, when to get ready, what sounds to listen for and what not to do, like jump in before the previous heat had left the water.

Like others, of course, I made mistakes and the sting in eye and lump in throat was rarely related to the result but the result of not doing the best you could have done, not speaking the language of swimming well enough to follow the rules and follow the basic signage of the sport. I learned, too, that officials are not always right; could be arrogant and aloof and uncaring – though many were quite the opposite of all of that.

How well I learned to listen to the water is hard to fathom but ‘feel for water’ felt like the glue and grammar of the language of swimming: the more you understood it, the further you could get, the bigger the thrill, the deeper the understanding. Speed, which relies on a much bigger lexicon, was a happy consequence of feel somewhat feline in nature: sometimes it sat in your lap, made you feel as though you belonged to it and it to you, at other times it turned its head and walked on by as if it had never known you.

Heavy water, for me, was cold. We 10 year-olds had a few escapes in spring through autumn (fall), some with permission, some not. At 25m, there was a boom, an open-air pool divider suspended from the sides of the tank. Go down just over a metre and you could swim under the structure and find yourself under a bridge in slightly warmer waters, swimming with beetles and other insects that had come a cropper. Unseen, you might skip a couple of lengths (or more) and you learned what 30 to 40 seconds felt like in a still, blind and clock-free world until your lane mates were back at the wall.

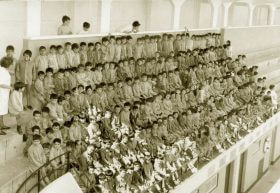

Algés in winter – Photo Courtesy: Antigos alunos do Algés, Facebook

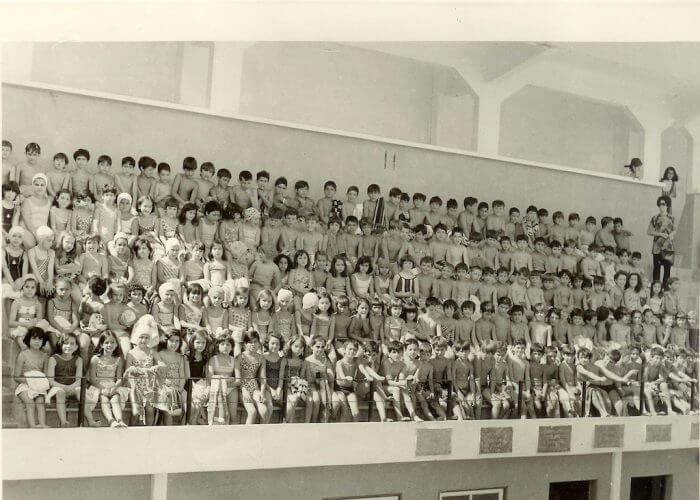

Algés, the stands in summer – Photo Courtesy: Antigos alunos do Algés, Facebook

In winter, the pool got covered by a giant balloon of tarpaulin-like material for a roof, kept in place by tethers and warm air. In spring, when the balloon was floated off and packed away (we often lost a few days of pool training at shift of seasons) and the sun had not been warm long enough to help the ailing plant, the water felt like ice.

The coaches would give us incentives: after the next set, you all get 10 minutes on the “bancadas”, the concrete stands that stretched heavenward on all sides of the pool, rounded at each corner. The place was a sun trap, the concrete in spring, warm to the touch and a relief from the big chill; in summer it burned your skin off if you forgot to put your towel down first.

A Visit Down Memory Lane At Algés

On a visit to the club last year, I was shown around the old place by my old teammate Rui Paulo and Emilio Frischknect, younger brother of Paulo Frischknect, a former European junior champion coached by my father and selected to race at the 1976 Olympic Games aged 15. Paulo raced at Moscow 1980, too.

Algés e Dafundo, the main pool – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

They’ve put a permanent roof on the old place – but beyond the windows, you can still see those old bancadas stretching off into the sky of blue above. Where my hiding place in the changing room used to be is now the coaches’ office and trophy corner; many of the plaques celebrating the club’s successes are in the main entrance hall with trophy cabinets – and on the wall in boardroom and offices; the trough around the main tank has been filled in, the head of the coach no longer at water level as it used to be; and the pool itself has been modernised – but not so much that I couldn’t work out some of the places where the walls around the water whisper yet of us, the old young swimmers of Algés e Dafundo.

The club has programs for gymnastics, sailing, judo, basketball and triathlon (with training facilities on the floor above the pool, now there’s a roof) as well as the swimming division, a multi-sports subsidisation model rare these days. Those sports are what sustain Algés but as a member of the F.C. Porto club in years that followed our time in Lisbon, I became aware of a bigger version of the model, one in which professional football revenues helped pay for many other sports, filtering money from the popularity and draw of stadia with capacity of 60,000 and more.

If it was cold in morning training, when many of my age peers were not there, I’d be allowed to go down to the pool in the plant. It was warm. I was alone. I had my set to do – and I did it as if it were race day: each swim was part competition, part commentary of that race in my head, spoken to self in the manner of the writing I’d read in all those books and magazines and articles written by the likes of swimming writer Pat Besford from Blackpool’s Derby Baths, Crystal Palace in London and others venues I’d been lucky enough to visit at a time when the press bench had 20-30 correspondents in place taking notes and filing reports on domestic racing alone.

There are national championships featuring Adam Peaty these days at which five reporters is a happy crop. At a time of Adam Peaty. Somewhere down the years, swimming lost its place on the conveyor belt of sport … a piece for another time.

The Munich Olympics in 1972 made my personal pool of dreams all the more thrilling. Now, I could identify the people I’d met through a colour TV. Now, I could tell which nations were in which lanes at a glance through their national suits. I cheered on Shane Gould and Roland Matthes, David Wilkie and delighted in seeing so many of those I’d met in London the year before.

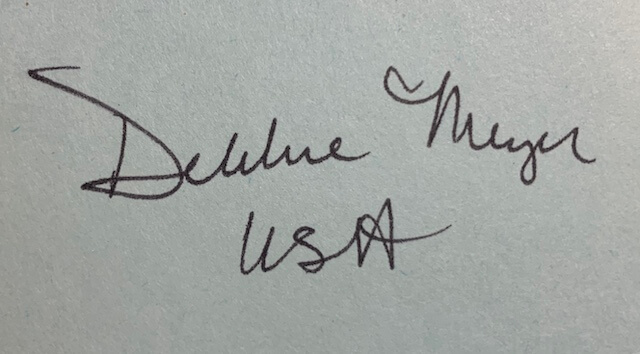

Two words that spell excellence in her own handwriting – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

I would soon become conscious of time passing and nothing being forever. In London in 1971, I’d met Debbie Meyer. She, too, signed my autograph book. And then, on the way to Munich, she was gone; she’d had enough, done enough and wanted to move on. Gould was the new big name, a shooting star in outer orbit – and then, not long after, she was gone too, just as a city called Belgrade was about to host the first World Championships. I would meet both of them again later in our swimming lives in a context but not a world apart, their contribution to swimming constant, the resonance of their days at the top of their racing game reaching my ear like a favourite tune you never tire of.

It was Mike Wenden, the double Olympic champion on 1968 who was the captain on the team Gould lit up in 1972, who said:

“Shane was like a high-decibel concert that had such an impact it left your ears ringing. But it also left you humming the tunes long after it all came to an end.”

How true. I remember sitting at my dad’s desk and reading an article by Besford in which she asked “do they ever come back?” Gould would neither come back nor, I would come to understand much later in life, did she ever leave, swimming a part of her identity but not simply through the three golds and two other solo medals that set an Olympic record for solo success among women that stands to this day.

Resonance, the song of swimming, a language of the sport as solid as the lexicon that flows through aquatic, blocks, boards, caps, flippers, goggles, lanes, lines, log books, taper, togs, turns and much else to the water it all took place in.

I lived all that and my own Olympic world those early mornings far from the demands of the 10x400s up on the blackboard in the pool above my head. The feeling was one of absolute freedom, to whatever tune that came to mind. The races were epic, the commentaries in my head glorious, the crowd in my mind’s eye wild, the days long. They ended after swimming with a meal and homework that had not been finished down at the pool waiting for the end of the senior session. Last thing, there were two bags to pack, one for swimming, the other for school – and it was down to me to pack my things and know I’d got it right.

Most days started around 5am. My sister, Debbie, was among those who were not so keen on the early starts until the surface was broken, the chill quickly subsided and the water reminded them that they were in their element.

Some of the medals won racing as a boy for Algés – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

I never did mind the dawn chorus of swim sessions: they were, for the most part, something I relished. It helped, of course, to know that the pool below ground was there to transport me away to Olympian heights and endless dolphin kicks that I could never get enough of (and train for the medals real that I won in the midst of all the fun).

Goggles would change the perception of underwater, of course, but the feeling, blind or otherwise, was what counted. From an early age, like many of you, I assume, I would stick my arm out of the window of our car as it sped along and feel my palm being buffeted, notice how a slight change of angle meant you could ride the air to the outer reaches of a range beyond which you lost “control” of the low.

Year later, as a journalist, I would speak to Patrick Miley, helicopter pilot and part-time coach to a full-time professional called Hannah Miley, who happened to be his resolute daughter, too. We were talking about motion through elements, the flight of birds, the way helicopter lift worked and how that might all be applied to swimming and that thing called “feel for water”.

Like so many moments growing up at Algés, the talk with Miley was ‘home’, someone who knew (and technically knew more) what I had known as a child. He’d held his hand out of the car window, too, as a boy. I liked to stand out in the rain, my face upwards to the tap trend on. I can’t recall if Patrick said he did, too, but he’s long struck me as someone who might.

In the afternoon at Algés getting on for a half a century ago, the underground option was out of bounds and my only escape was the showers, up a set of stairs, to the left, straight through, second door on the right: warm water. If we took too long, we would hear a voice shouting us back. It might be Patrone (the old ‘Boss’ I first referred to here as Patrao before being corrected 🙂 , the coach for life at Algés who worked with generations of swimmers for more than half a century. If we heard silence not long after, we knew someone would be coming to get us, so we hid in the lockers, quiet as mice, all the easier to hear “you’ve got 2 minutes … or it’s 10x400s, no bancadas”.

Sometimes, we would swim before the seniors were in the pool and then had to wait for older siblings to be done. I can’t recall the number of times, we – that’s Paula and sister Helena, Joanna, Mario, Carlos, Zé, Xixa, Rui and many more – used a ‘secret’ passage we’d found running from a room under the stands through a hole in the wall and on to the back of the big screen belonging to the neighbouring cinema. We’d make giant shadows and shapes on the screen and then run like hell back from whence we came.

Not long after we’d taken up a serene butter-wouldn’t-melt pose in the stands, we’d see the cinema manager come flying round the corner onto the pool deck screaming at the coaches, who would shrug and point up at we of angelic and innocent demeanour. Surely, not them!?

Pasteis de Nata – don’t forget the slimming pill – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

When the manager had gone off in a huff, we knew we’d have moments to escape consequence and we knew every escape hatch in the place, including passageways through the local school attached to the sports club. We’d often go where young kids go when avoiding trouble: our mothers could often be found in a nearby cafe drinking coffee and a slice of cake, some with a slimming tablet as chaser, among the more complex layers of language and behaviour to fathom as a child.

The Algés bus – Photo Courtesy: Antigos Alunos De Algés e Dafundo

For weekend away meets, the club had a green and white bus (pictured right). There were no seat belts, nor tablets, iPods, iPads, smart phones, movies on the go. We talked to each other, we played word Games and wrote coded love letters on paper folded to open in different ways to give different answers, with a black field left for the answer.

The bus was also a classroom for cursing: forced by our size and lack of status to sit at the front, we would listen to the language coming from the back before sneaking out of our seats in search of explanation, much to the merriment of those who had knowledge we did not. It was in that bus that I learned Portuguese songs I can still sing today; where I heard Fado being sung and explained.

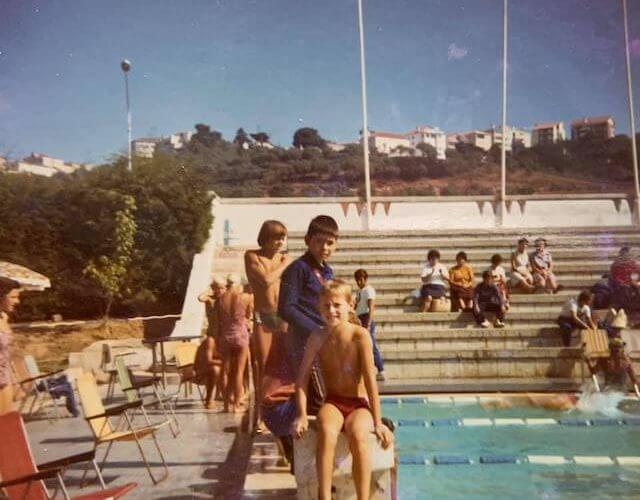

Craig Lord, aged 11 at a competition pool in Coimbra that no longer exists – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

In the pool almost 50 years back, we worked well, had fun, set goals and looked forward not to the 100m whatever but the relays and beating teams from Benfica and other clubs if we could. Our hair was bleached, mine white and sometimes with copper-coloured green streaks, our skins were tanned and the first lesson of school each day was passed in a haze of chlorine vapours and an urge to nod off, apart from in winter: we would eat breakfast from our boxes as Atlantic rollers crashed into the train we travelled on from pool to school, the window seat only for the likes of those who want the front row on the roller-coaster to get the full blast with uninterrupted view.

At that time in life, we learn so many languages, including trust, caution, instinct, peripheral awareness and much else. We never look back on our own language and consider its learning to have been a chore: it was just a part of us. Any language is like that if you learn it young enough, swimming just as much as Portuguese.

I remember, quite vividly, that first day at our new school, St. Julians: my sister and I were told that Portuguese classes would be conducted in Portuguese only and that rule would start straight after the sentence “hello, I’m Senhora Policarpo and here are the books you’ll be using – agora, vamos falar Português” (now, we’ll speak Portuguese) – and so it was.

For me, at my young age, there was little difference between English, Portuguese, hand and shoulder signals and facial expressions (Portuguese is often a gestural language), swimming, a log book, a training set, a result sheet. They were all just part of life’s language and a set of keys to deeper understanding of the games, the fun, the threat, the joy, the sorrow, the mood music.

The crew – some of my training group and partners in mischief – Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

The pool at Algés was all of life and the lives of us all, from different perspectives. My parents were faced with a more onerous than me and my sister when it came to language, not only as a book of words spoken but in the depth of meaning, cultural outlook and the values they had brought with them from the north of England via ancestry both Irish and Scottish.

Dad, as coach, was surrounded all day long by the Portuguese he would need to learn, starting with “livres, costas, bruços, mariposa, estilos, pernas, braços, cem metros and much else” (free, back, breast, ‘fly and medley, legs, arms, 100m ). He would need to know that such simple terms came in different versions and words from former colonies Angola, Mozambique and Brazil, where ‘fly was borboletta and medley medley not estilos.

Mum was treated to the kindest of strangers who became friends and part of the fabric of our lives. The Bugalho family merits special mention for the depth of help and friendship and guidance they provided to my parents.

My mother would find herself whisked off to open markets and shops, taught the words for things she would need and the linking phrases useful for stringing sentences. My parents also had formal lessons but while none of that was easy, the hardest part was in English.

I came home one day when I skipped afternoon training to find her both upset and angry. She’d had a visit from the catholic priest and head of religious instruction at our school. He’d come to take tea but his real purpose was soon clear: would it not be better to move house and be closer to ‘your own people’.

She asked him what he meant. The Portuguese, he opined, were ‘awfully nice’ but they weren’t ‘like us’ and it might be ‘better for you’ if you were to move and ‘live closer to people more like yourselves’. She threw him out. I was very happy about that. I’d been handed a piece of paper from a boy across the bench in our class. It was a pencil drawing of our room, the one underneath it, and a hole in the floor through which the priest had fallen, his legs dangling in mid air, his outsized head stuck in the classroom above. The caption read “Father Fatty”.

He saw the paper in my hand, snatched it away and then proceeded to thrash me with a ruler until my knuckles bled. I was 10. And given what else has unfolded down the years with priests, lucky, too.

As for drawing blood, the more damaging pain is often that which cannot be seen, as I would learn through events in swimming that resonate with the troubling events unfolding in the United States and far beyond in the wake of the brutal death of George Floyd.

An Age Of Cholera, Revolution And Innocence Upended

Photo Courtesy: Craig Lord

We lived at a time of cholera. In April-November 1974, Portugal suffered an epidemic that put 2,467 in hospital and caused 48 deaths. Most of the country was affected, with 17 of the 18 districts reporting cases. Shellfish was its hiding place: an epidemiologic study found that a history of consumption of raw or poorly cooked cockles was significantly more common among cholera patients than among paired controls. Water from a spring and a brand of commercially bottled water were also found to be vehicles for transmission of cholera.

The same year saw the Carnation Revolution, in which just 4 people lost their lives. The Revolução dos Cravos, also known as the 25 April (Portuguese: 25 de Abril), was initially a military coup in Lisbon which overthrew the authoritarian Estado Novo regime, brought the Portuguese Colonial War to an end and started a revolutionary process that would result in a democratic Portugal.

We were at Algés for morning training when the news came through that a revolution was under way. Everyone was sent home and a call to the school confirmed that there would be no lessons that day. It was a warm-sunny day and there was nothing we could do. My parents made a picnic and we set off to the beach. Along the coastal road heading west from Lisbon, our car was stopped by an armed soldier standing in front of a tank.

He approached the window and asked my dad where we were going. hadn’t we heard that there was a revolution underway? Yes, but we had full faith in him and his colleagues to get it sorted. The soldier looked at our passports, looked at the picnic basket, sighed, shrugged and waved us through. It was a lovely day on the beach and by the time we returned home, Portugal had sent its key dictatorship figures packing and was on the way to democracy.

The end of the Colonial War soon meant that people from Mozambique, Angola and elsewhere were free to come and go. Visiting teams would be seen more often – and among those who came to stay permanently was a young swimmer called Rui Abreu.

He didn’t swim for Algés but Coimbra, where his parents had settled on their move to Portugal. He was a rival of one of the great prospects at Algés, Paulo Frischknecht. The two, both a year older than me, would end up being selected at 14 for the 1976 Olympic Games. They raced in Montreal at 15 and became close friends.

I mention Rui Abreu for a specific reason that I’d never even thought about as a child: he was a hugely talented, lanky … and he was the son of an Indian father and black African mother who had grown up with white friends at school and pool. He had never thought of himself as being black. Yes, that is what you’re reading, it is what I mean, more so now that ever before in the context of current events linked to a woeful thread of history that transcends the United States and has replaced COVID-19 as the headline after months of nothing else.

Try years of nothing else. That’s what the Black Lives Matter movement and those empathising with it point out with the power of truth behind them.

Remembering Rui Abreu

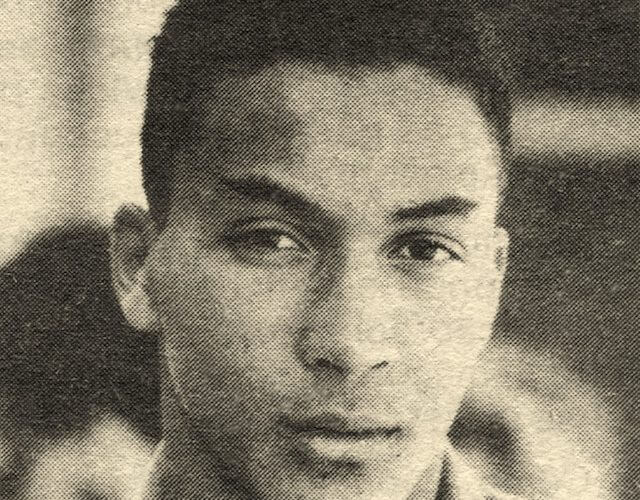

Rui Abreu – Photo Courtesy: Diario de Noticias ragout

Closing my eyes, embracing the child within as I recall our young lives, I see Rui Abreu on the deck and in the water. His natural skill and athleticism drew the eye. I recall my dad getting a group of 11-14 year-olds to gather in readiness to watch Rui swim a 100m backstroke race. I seem to recall that we were in Coimbra at the pool pictured, his adopted home town the university town in between Lisbon and Oporto that faces west across the Atlantic and boasts one of the most glorious libraries in the world.

The Johannine Library – Photo Courtesy: Portuguese Tourist Office

The Johannine Library is Baroque and was built in the 18th century during the reign of the Portuguese King John V. The library is a National Monument and has what is described as “a priceless historical value”. The library is noted as being one of two in the world whose books are protected from insects by the presence of a colony of bats: at night, the bats consume the insects that appear, eliminating the pest and assisting the maintenance of the stacks. Each night, workers cover the credenzas with sheets of leather. In the morning the library is cleaned of bat guano and the cycle of protection for books, food for bats goes on.

Sadly, no-one could save Rui Abreu. I have a vague memory of him setting the national record that day in Coimbra. But that wasn’t the point. What my dad, ‘Mister’, as his swimmers called him, wanted us to see was the smoothness, the roll of the torso, the fixed head, the interruption-free, momentum-loaded progress Rui made in his element, at one with water.

To us, Rui was just Rui, a smiling, aesthetic presence in our swimming lives. I mention “just Rui” to Paulo Frischknecht, who says “absolutely, exactly that: he was always and will always be just Rui to us, not ‘the black swimmer’.”

How could he be that? If we ask that question, Frischknecht recalls him asking it too. Born of a black Mozambican mother and an Indian father, Rui had grown up in largely white company in a society – and certainly a swimming community – that made nothing of the colour of his skin. Since he was about 10, he’d been visiting Portugal with swimming teams from Mozambique that included youngsters of Asian, Black and White descent. In terms of skin colour and complexion, I was far more ‘other’ than Rui, my skin fairer, my hair white, my native language English, my education at the international school.

Rui also made it to Moscow 1980 and although the United States had boycotted the Games, left its swimmers to wonder forever more what might have been, college recruiting agents from the USA did make the trip to the Russian capital. It was after I’d returned to Britain with my family that we got news that Rui was off to Cleveland University in Ohio.

I recall my father looking troubled and simply asking ‘why?’ He was not opposed to swimmers taking up American scholarships so I asked why in turn. He recalled the story of a stopover staging camp in New York on the way to the 1976 Olympic Games with the Portuguese team. They had gone out for a meal on their first evening there. Before they could sit down, they were turned away. My father asked for an explanation and was told “we don’t serve blacks”.

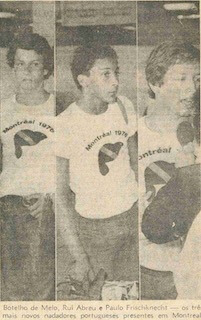

Rui was 15 years old. Not much was made of it and he was protected from the truth of what had just happened. They found another place to eat and Rui, Paulo, and another of their age peers from Mozambique, António Botelho de Melo, went on to enjoy a happy debut Games in Montreal, though Paulo – whose brother Jacob was also a national champion and went on to be an expert in sports medicine, another swimming brother, Miguel, is the head coach at Algés and one of Portugal’s top coaches – recalls the first time Rui was made to feel that he was different to his team-mates:

“On the plane to Montreal we were given landing cards. I had to ask the steward to help because I had no idea what Caucasian was. Rui had a hard time with it too. He’d never seen himself through colour. He was mixed race but we were being asked to tick boxes to mark us out on racial grounds. We’re all members of the human race; colour wasn’t important to us and it shouldn’t be important now.”

Skip forward 6 years and on Halloween 1982, Rui Abreu is found dead in his dorm in Cleveland, having taken his own life. It is his mother’s birthday. He leaves two notes. One states that he wants to be buried there in Cleveland. It is not certain why but he may have wanted to save his parents the cost of repatriation.

The second note is to his mother, the full contents of the letter a private affair. In time, Rui’s remains make it back to Coimbra, where his grave can be found.

Rui Abreu’s resting place

I called Paulo Frischknect this week to have a long overdue catch up on our swimming days, recall the events of 1976 and the restaurant that refused to “serve blacks” and asked if I was right to feel that racial discrimination had played a part in Rui’s suicide.

Three mid-teens representing Portugal at Montreal 1976 – Photo Courtesy: A Bola

Paulo explains the background: American recruiters had made offers and the first one Rui received was for Cleveland. Desperate to get an education while continuing to swim, he accepted, the consequence of that being that he would not need to serve two years obligatory national service in the army. Frischknecht advised his friend to wait, see what other offers might come in. He would wait because he wanted a college in the sunshine belt to match the kind of climate he was used to back home. He landed a place at the University of Southern California.

Rui and Paulo made an arrangement: they would call each other twice a week, taking turns to foot the bill, to support each other and ask if all was well. Paulo recalls:

“Rui was quite anxious to leave and try a new life away from Mozambique and somewhere that would provide the resource. he needed to study and swim. His parents were struggling financially – and this was a fine opportunity. In Portugal he had singed for Benfica but by 1982, he had grown tired of the life he was leading, no longer wanted to swim but felt like he was in a maze of bad options. We talked about that but I had no idea how bad he felt about it.

“In the last call the week he died he spoke about not wanting to keep swimming. He’d had enough. But he knew that if he stopped swimming, he could not keep his scholarship. If he went home, he had different problems: he would be drafted into the army; then there was the problem of Benfica – there was a contract in place and swim a further two years until the contract ended. “

The tension of it all came on top of something else: a crisis of identity. There was the lesser matter of the weather: Rui, who felt most at home on a beach, in the wash and wave, in an open-air pool in warm weather, was in Cleveland. It had been grey and even snowing.

And then there was this underpinning a sense of lost identity in a routine of dorm-classes-pool as a star of Division II breaking all the pool records at the time. Paulo explains:

“He was not used to being segregated. He himself used to say that he felty ‘white’ and did not identify himself as ‘black’. If anything, he was of mixed race, mulato, his father Indian, his mother a very beautiful black African lady. None of that mattered. He was one of us, always had been and no-one cared about the colour of anyone’s skin. But in the U.S. at that time he was made to feel ‘black’ for the first time.

“He had tried to join the social groups the white swimmers at Cleveland belonged to. There was pressure to deliver results in the pool but the moment he stepped out of the pool he was on his own in a non-swimming, black community he didn’t identify with and could not relate to.”

Rui had grown up in swimming and school among white friends, Paulo noted before adding: “When he tried to socialise with white people in Cleveland, he was basically told ‘no, don’t hang out with us.”

Racism was heavy in the air well beyond Cleveland, says Paulo, of Portuguese and Swiss heritage. He recalled being picked on for having “Latino” and black friends. “Some team members would say openly to me “why are you speaking to the blacks. You’re supposed to hang out with us. It was so strange, so alien to me. It was like they were saying ‘you’re European, the people we can trust but if you hang out with them, we’ll treat you like a Latino and you can’t hang out with us.”

Forced into company that was not athletic, he was introduced to hard drugs and for a while he took them just to feel accepted by the only people he was able to socialise with. Says Paulo:

“It was a disaster cocktail. He had nowhere to go. In his mind, if he had gone home, he would never graduate, would place himself in financial difficulty. He would also have to join the army and he didn’t want to. He seemed to come to the view that his only way out was suicide. I’d told him on our Wednesday call that we’d talk again, as usual, at the weekend but when I did I was told I couldn’t talk to him. Rui was supposed to have been going to a Halloween party and now this guy was telling me ‘you can’t speak to him’. I was pretty upset and then he told me he was an officer and that Rui had taken his own life.”

We exchanged views on our own experience in Portugal in the 1970s, when Rui would have suffered fewer stereotype references than I would: British people were known as ‘Bifes’, or ‘steaks’ because they turn pink in the (heat) sun. Paulo remembered constant references to ‘Bifes’. It hadn’t bothered me too much but I recall not liking it simply because it was a form of being singled out for a physical appearance that set us apart from the majority.

Paulo then recalled that something similar happened to him: to be “Swiss” was not an insult so he found himself being called ‘German’ instead as a code word for ‘Nazi’ but with this twist: “They also called me ‘hey, Jew’, because of the shape of my nose. At the time you feel its innocent enough but now you reflect, it was actually hurtful and was meant to hurt.”

And that is what Rui Abreu had felt like in the last year of his young life. Says Paulo:

“It had been so hard for him to be so far away from home. I recalled at one time thinking to myself. thank God I’m white, simply because I could see what was happening if you weren’t. I never thought of Rui as a black person; just a person. He was and remains a friend for life .”

The Rui Abreu Pool

In September 2004, Coimbra honoured Rui Abreu by naming a new pool at the “Pedrulha” complex after him. Rui’s family and friends were present to hear homage paid to him. One citation recalled him in these terms:

“A stunning river of beauty, vigour and life was born in the waters of the pool where he swam.”

I understood instantly what they meant. So did Paulo, who first met Rui when they were 11 and growing up together a decade before Abreu would take his life.

Aesthetic, powerful, at one with water and never without a smile to give, Rui Abreu, the first Portuguese swimmer to break one minute over 100m backstroke, was a teenager other teenagers looked up to back in the day, both for his skill and talent and his kind nature.

His mother, Mercedes Abreu, speaking 20 years after her son’s death, said of the pool naming: “I am so happy, I honestly never thought this could happen. I am really grateful.”

Paulo Frichknecht, who would become president of the Portuguese Swimming Federation (FPN) and give the country its first seat on the ruling Bureau at FINA (since lost), gave a speech that day, too. He said:

“Rui is a champion. Only a champion would bring so many people here this day, 22 years after he left us, twice as long as the time we knew each other for. Whoever dies is a part of whoever lived in his company. The most important thing he brought was the example of life that he gave us as a person, friend and athlete. Friendship is the most important thing you can cultivate in your time as a sportsperson. Rui was a friend of ours, he was one of us.”

When I recall Rui Abreu, I see him yet as I saw him at 10 and 11 years of age. A warm smile, soaring skill, boundless potential.

If we know a song of swimming, of what it means to have ‘feel’ for water, to be at one with the element, to strive through discipline, determination and dedication, to forge friendships for life; to leave a block knowing what you’ve worked for; to take heart in the achievement of others; to know the thrill of driving off a wall, catching the wave, in pool or at sea; if we know what swimming means to us; if we understand its lexicon and lore, then we’ll know, too, that we speak the same language as Rui Abreu.

We share the same spirit. Human spirit. It knows no bounds but those we choose to impose on it. It knows no prejudices barring those we ask of it. It speaks a common language

Like Rui, my underground Algés pool of Olympic dreams is no more. The spirit of people and the significance of places such as my childhood swimming haunt live on.

The world ‘saudades’ is one of the most famous in the Portuguese language: it sums up longing, melancholy, nostalgia in a way that often means ‘we know we can’t turn the clock back, nor perhaps do we ant to, but we can say that those were the best of times and we miss them. It sums up how many feel about Rui all these decades on. And how I feel about Algés e Dafundo.

NB: As a result of this feature, I learned that in the year leading up to the Moscow Olympics, Rui and his sister Luciana Abreu and Alexandre Yokochi all trained at the pool in Algés at a time when Benfica’s pool was being renovated. The river flows.

Snapshots Of A Childhood Swimming Life At Algés e Dafundo

Beautifully written. I too swam with Rui, I am Antonio Botelho de Melo’s sister, and recall him with great warmth

What a lovely note, Clotilde. Thank you 🙂 I hope you and Antonio are well. I enjoy looking at the history on his blog from time to time. Saudades. Stay well.

You too, continue the good work

Thank you Craig for your memories! Best,

I also have great memories from this pool. And it was really important to understand better what happened to Rui.

Thank you Craig!

see you in the water.

Wonderful text. I am Portuguese and was starting my coaching career in Cascais at the time many of the events you mentioned were unfolding. (I’m slighter older than you.) I remember you and your dad at Algés e Dafundo. (I remember how a friend of mine who was a swimmer for Algés back then told me one day that you had corrected his English once once when he said “You have to go more fast”!). I remember that I was told that Rui had died outside the Areeiro swimming pool (you may remember that one, in central Lisbon…), just before another afternoon session as a coach with “Sporting”. And I obviously remember Rui’s smile and his magnificent feel for the water. Just a correction, if you won’t take it amiss: the elderly coach in the photo whom you identify as “Patrao” was actually called “Patrone” (He was the Portuguese “Doc Counsilman” of the day.) About 20 years ago they named the riverside promenade in Algés (where the garde is, just by the Marginal) after him.

Thanks for the memories. Saudade!

Take care!

Hi Julio. Thanks for your lovely comment. Yes, Rui always looked so very smooth and at one with water 🙂 Patrao! Patrone, of course! Obrigado.. I’m glad they named that stretch of the promenade after him – lovely 🙂 Tempos para guardar em nossos corações e mentes para sempre. Saudade de volta para ti. Um abraço, C