7 Essentials of Open Water Success

By Steven Munatones

LOS ANGELES, California, September 23. JOHN Wooden, the legendary UCLA basketball coach, is renowned for being a great educator who created one of the most profound definitions of success: the Pyramid of Success. Wooden's Pyramid of Success includes 15 blocks, from industriousness to enthusiasm.

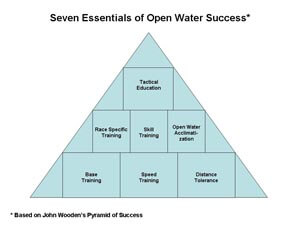

Using Wooden's Pyramid of Success concept, the Seven Essentials to Open Water Success describes the optimal training regimen for a successful open water swimmer, whether the athlete is aiming to do a ½-mile swim for the first time, cross the English Channel or win the Olympic 10K Marathon Swim.

The cornerstones of the Open Water Pyramid comprises of Base Training, Speed Training and Distance Tolerance. These training fundamentals, referred to as the base, are well-known and understood by pool coaches and are rooted in the distance pool training methodologies used since the early 1970s.

At the mid-level of the Open Water Pyramid, the key components of success are Race Specific Training, Skill Training and Open Water Acclimatization. These three training fundamentals are less well-known and rarely emphasized by coaches or athletes in their daily training regimens.

At the apex of the Pyramid is Tactical Education. This is the knowledge and understanding of what to do in a dynamic environment where one's competitors and the water conditions are variable. Athletes need to plan for, anticipate, adapt and respond to the ever-changing environment during competition. This education, which is vital to success, can only come from real-world experiences, observation and study.

The seven essentials include the following:

1. Base Training: Getting in shape during pre- and mid-season by swimming hundreds of miles through daily and repeated aerobic training sets (e.g., 6,000 – 10,000 meter workouts). This is a basic component of competitive pool training programs.

2. Speed Training: Improving one's speed by focusing on up tempo swims including anaerobic training sets. This is another basic component of competitive pool training programs.

3. Distance Tolerance: Developing one's ability to swim the specific distance of one's chosen open water distance (e.g., 1500 meters, 10K or 20 miles). This is another basic component of distance freestyle training groups of competitive pool training programs.

4. Race Specific Training: Simulating open water race conditions in the pool or acclimating the swimmer to such conditions during open water training sessions. This includes pace-line sets, leap-frog sets and deck-ups. Pace-line sets are where groups of swimmers closely draft off of one another in the pool, changing pace and leaders throughout the set (e.g., 3 x 1000 with a change of leader every 100). Leap-frog sets are another example where the last swimmer sprints to the front of the group every 100 meters. Deck-up sets (10 x 100 @ 1:30) are where swimmers must immediately pull themselves out of the water and dive back into the pool after every 100. This simulates on-the-beach finishes when an athlete is swimming horizontally for a length of time and then must suddenly go vertical to run up to the open water finish. Deck-ups also assist the swimmer's preparation to make quick tactical moves during a race or in response to unexpected tactical moves by one's competitors because there are often heart rate spikes during a race.

5. Skill Training: Teaching the fine points of open water racing techniques requires feedings, sightings, starts, turns, positioning and navigation practices during pool practices or, ideally, in the open water. For feeding, swimmers can place gel packs in their swim suits to practice fluid in-take during main sets. For navigation and sightings, swimmers can do 6 x 400, but they must lift up their heads twice every fourth lap to sight balloons on the pool deck, moved around by the coach. For turns, swimmers can touch the wall, without doing a flip turn or pushing off the wall, during the last 2 laps of 5 x 200. For drafting, three swimmers can swim together with one swimmer slightly behind drafting for a set of 9 x 300 with a draft every third lap and descending by groups of three. To replicate start and finish conditions, swimmers sprint short distances (25's or 50's) with three swimmers per lane starting at the same time.

6. Open Water Acclimatization: Especially for newcomers to the sport, acclimatization is required to get swimmers familiar with the open water environment. This includes getting used to cold water, warm water and rough water. This also includes understanding – and experiencing – jellyfish, marine life, wind chop, boat fumes, oil slicks, kelp, fog and rain as well as swimming through waves and currents before one's race. It also includes "aggressive swimming" sets when a group of swimmers in a tight pack practices buoy turns and finish sprints where the swimmers purposefully knock off the goggles or swim cap of one chosen swimmer. These types of experiences are parts of open water races at one point or another. To be successful, these experiences must be encountered and mastered during training.

7. Tactical Education: Most importantly, swimmers must study and understand the dynamics of open water racing and know why and how packs get formed and why they take on certain shapes. Swimmers and coaches must understand, for example, why and how packs get strung out, where swimmers should tactically place themselves in the pack at different points during the race and the importance of hydration and feeding station techniques. These tactics should be reviewed while observing successful open water swimmers through film so questions can be asked and different scenarios can be studied. An example of who best to study is Olympic 10K champion Larisa Ilchenko, who is not the fastest 800-meter swimmer in open water competitions, but who never loses a major competition.

"Base Training, Speed Training and Distance Tolerance are taught by pool coaches," Gerry Rodrigues, coach of UCLA Bruin Masters said. "But different types of skills and sets are needed for success in open water competitions, whether it is a local lake swim or the Olympic 10K. Race Specific Training, Skill Training and Open Water Acclimatization are three additional types of training required to properly prepare for open water racing which is becoming increasingly competitive."

"Football players and their coaches study film. The best race car drivers know when to slow down the field or speed up. These athletes have an arsenal of tools that is necessary for victory. Open water swimmers similarly need an arsenal of tools to win. Before they jump in the water, swimmers need to know how to deal with each possible scenario that can present itself during a race. Even though some swimmers may have an innate tactical IQ, most athletes will have to learn."

"Knowing what these tools are is the first step. Knowing when and how to use these tools is the next step. It is really a tactical education – an oft-overlooked aspect of open water training – that separates consistent winners from the rest of the pack. This know-how and skills must be developed and will become the most important tools in this rapidly growing sport," explained Rodrigues, who has won over 100 races during his lengthy career.

With proper focus on the Seven Essentials of Open Water Success, swimmers can best position themselves for success in the open water.